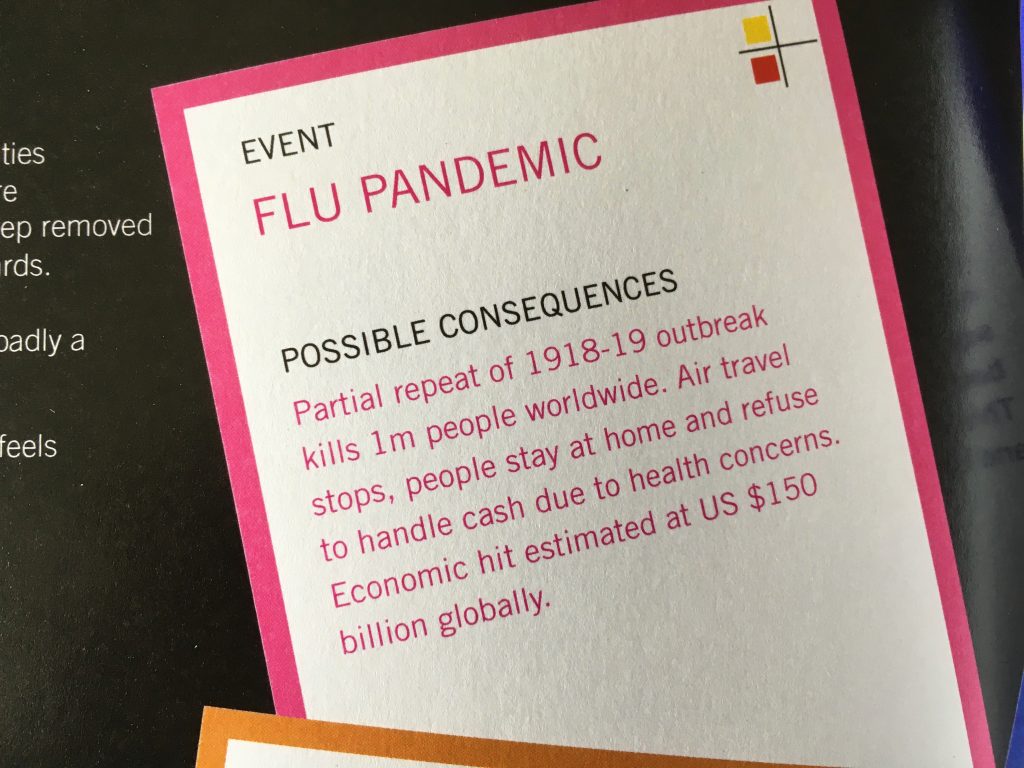

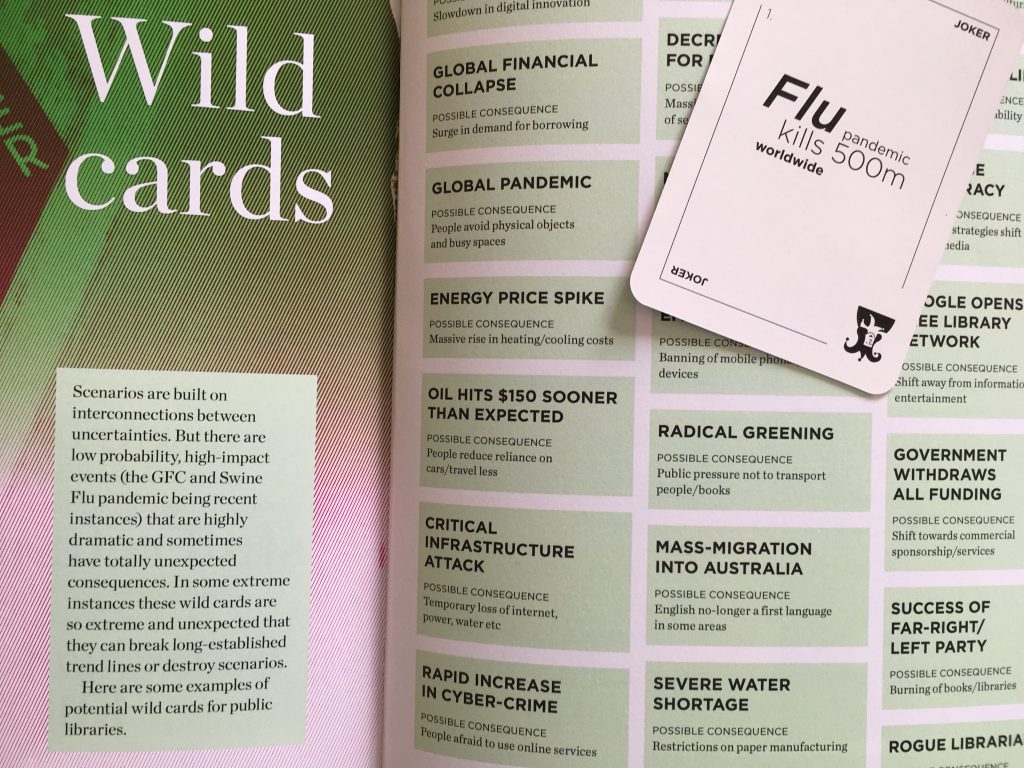

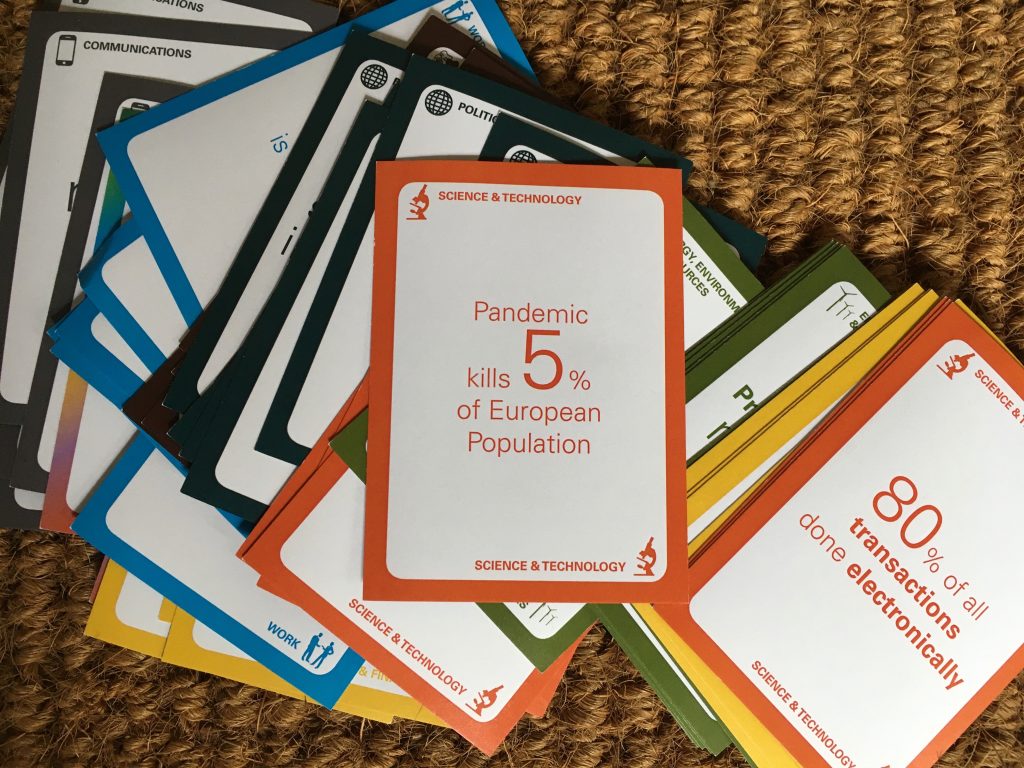

It was no so long ago, about three months ago from my fading memory, that pundits were predicting that life would be forever changed by the pandemic. “Nothing will ever be the same again” was the kind of headline I recall reading. No more going to work in an office, no more handshakes, no more getting on airplanes to travel to far flung places. We were all going to be humble and above all more human.

I’m not so sure about that. It’s hard to predict what will happen next, but I think it’s worth a go. My feeling at the moment is that there will not be a significant second wave. There will be outbreaks, but they will be dealt with by regional lockdowns or separation for certain groups of people. We are already seeing this, although what’s interesting to me is that any re-growth in cases is not being met by any similar growth in hospital admissions. Maybe cases are now among groups that are more able to fight the virus, or perhaps the virus has mutated into something less dangerous than before (as an aside, I’m also cynical about a vaccine on the basis that it seems to assume that there is a single strain and a single vaccine will thus defeat it). I am also optimistic that the global economy will snap back to business as usual faster than many people expect.

But back to change, or the lack of it.

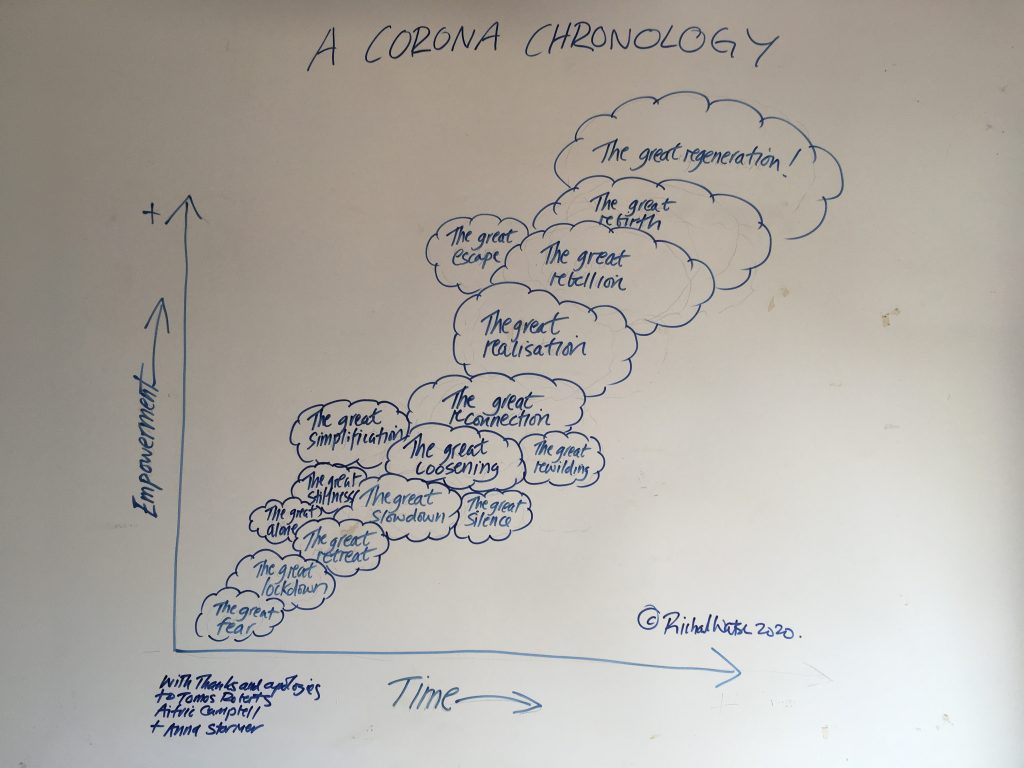

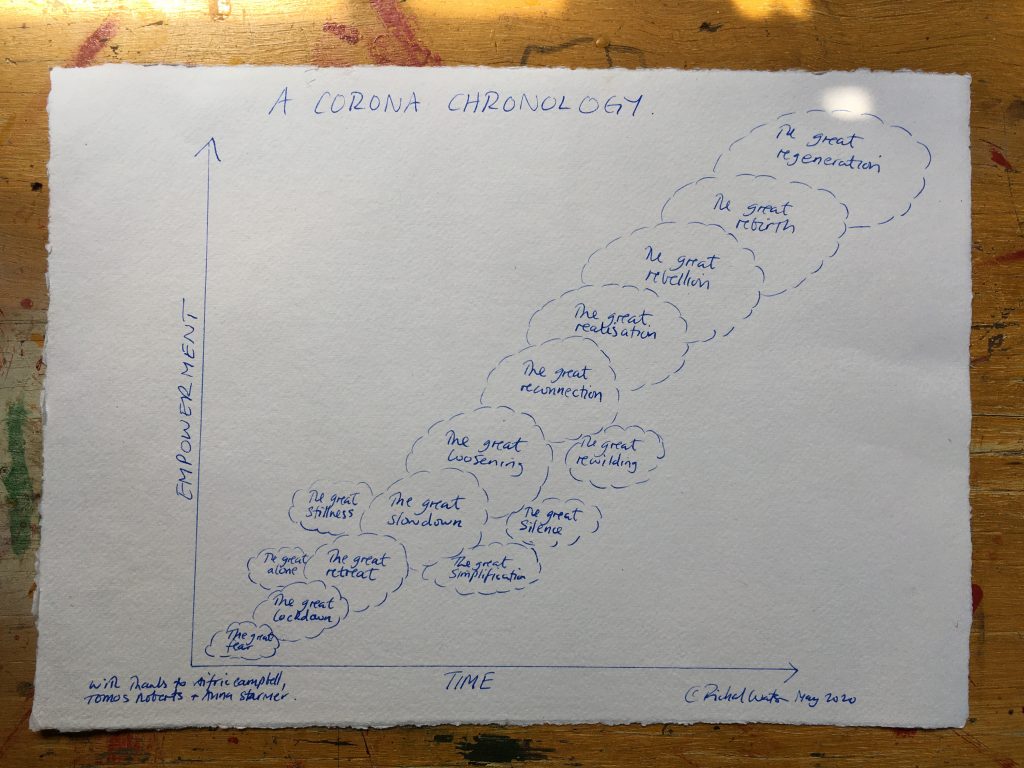

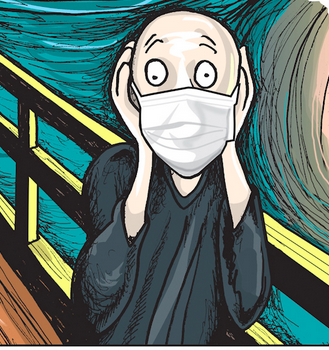

Janan Ganesh, writing in the FT, has observed that it is one thing to renounce an activity when it is no longer an option, another to continue to do so once a temptation has tangibly returned. My view is that many of our habits are hard-wired, built up over decades of familiarly and use. Moreover, human memories are increasingly short and there is probably a desire to forget what has just happened and move on. Therefore, many of our old ways will return and something resembling the outskirts of normal will be back before we know it. That sounds like a good thing, and it is on so many fronts, but it also perhaps represents the loss of a once in a generation opportunity to redesign how the world works. With the end of Covid-19 may come the death of hope for significant change.