That much promised link…

Monthly Archives: January 2011

The Future of Bookshops (and Work)

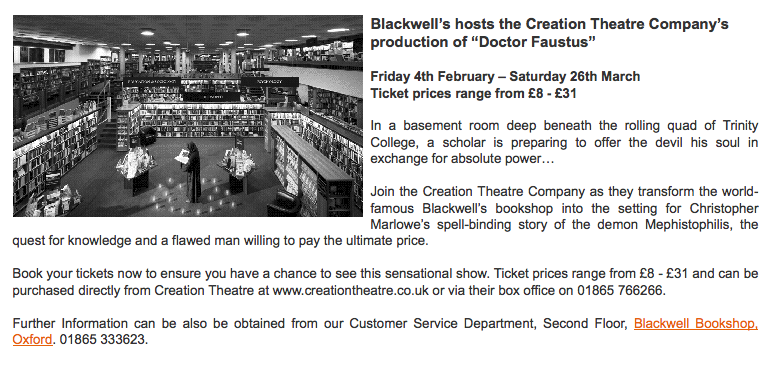

I forgot to say something. If you live around Oxford you simply must attend the Creation Theatre Company’s production of Doctor Faustus – amongst the books in Blackwell’s Bookshop (4 Feb-24 March). There’s also a panel discussion in the philosophy department on Feb 1. Bookshops and libraries (and maybe even pubs) take note – this is exactly the type of thing you should be doing.

Another thought. I mentioned the future of work event that I attended yesterday. As always the best bit was the Q&A. Two important points. First, before we talk about the future of work we should define what we mean by work. Why do we work? What’s work for? Clearly the answer isn’t simply “money.” Personally I think that cutting jobs to save money is shortsighted because work has social benefits at both an individual and collective level. Therefore, you may save money in the short term but end up creating bigger and more expensive problems due to the long-term social harm unemployment creates.

The second thought was that it’s all too easy to fall into the trap of only thinking about a small slice of society when you discuss the future of work. Most people don’t work in the knowledge economy and very few read Fast Company, Wired magazine and the Harvard Business Review. Therefore, whilst discussions about fluid, networked corporations and digital nomads are true they are irrelevant for the person stacking the supermarket shelves, working on a production line or fixing the road. What does the future of work look like for these people?

Out and about

Update. Event in London on the future of work followed by a flying visit to Oxford to do a talk at Blackwell’s bookshop. (Thanks Zool). Bright audience. Very bright audience. To misquote Yeats, it’s a wonder that anyone does anything in Oxford. The whole place just seems to be built to encourage people to think about the past and dream about the future. Nice comment on the Blackwell’s blog about “literary festivals (and, by extension of that, all programmes of author events) being almost like the new public meetings – not just individual occasions of interest but actual forums where the world moves forward through discussion, free and frank exchanges of views, philosophical extemporisations.” Marvelous stuff.

After breakfast I popped into the Ashmolean Museum on a whim and nearly burst into tears it was so beautiful. (Where there is beauty lays truth etc). Then back to London to have lunch with an old boss and on to for a meeting at the London Business School. Then back home to open an old bottle of red and watch some fantastically gripping reality TV.

The talk at Blackwell’s was based on the talk I did at the RSA, but tightened up a bit. If you are interested (i.e. you have a 21-hour flight to Sydney coming up and don’t have anything to read) here’s the transcript.

————-

The book (Future Minds) is about the impact of digital culture. It’s about how 4 billion mobile phones, 2 billion PCs, 550 million Facebook accounts and a Googlezillion internet searches, texts, tweets, zaps and pokes are changing how we think. At least that’s what the book ended up being about.

The reason I wrote the book is that I had an idea. An idea that occurred to me early one morning when I was looking out from the rooftop deck of a hotel in Sydney. Interestingly, I was the only person doing this. Everyone else was frantically answering calls or tapping Blackberry’s.

The idea I had was whether or not physical spaces, like the one I was in, influence thinking. But then I thought to myself – would I be having this thought if I were on the phone, looking at a computer screen, in a basement in London? I thought then – and I still think now – that the answer is no.

Modern life is changing how we think, but perhaps the clarity to see this only comes with a certain distance or detachment.

My original idea was to write a book about how physical spaces (like hotels or bookshops) influence thinking. A book about architecture essentially.

However, my publisher pointed out that such a book would probably sell about 3 copies, so I broadened the remit to include virtual spaces, digital devices and eventually screen culture.

It thus became a book about the future of thinking with a set of social and technological trends as the unifying force. Ultimately, though, it’s about something else. It’s about our addiction to digital technology and the way this is changing our relationships with each other.

The book is split into three parts.

The first part is about how attitudes and behaviours are changing. It looks at teens and pre-teens and considers, amongst other things, connectivity, multitasking, electronic games, the fate of physical books and whether IQ tests could be making kids stupid.

The second part of the book is about why this matters. This section looks at how our minds are different to machines, considers where ideas come from and contains a section about paperless offices and a plea for more organised chaos.

The third and final section is then about what we, as individuals and institutions, can do about a world choked with too much information and distraction.

I’d like to look briefly at each of the three sections.

We are constantly connected nowadays. This is largely due to digital technology.

A decade ago there were fewer than 500 million mobile phone subscribers worldwide. Now there are 4.6 Billion. In the UK 50% of children aged between 5 and 9 now own a mobile phone.

When I was growing up there was one only phone in the house, which represented a physical location, and it didn’t take messages. There was also just one TV, which had 3 channels and these all closed down at around midnight. Children’s TV was on for just two hours on two channels. Nowadays, 79% of British kids have a TV in their bedroom and children’s programming never ends if you have satellite or cable.

In the US it’s worse. 1/3 of kids in the US live in a home in which the TV is on “always” or “most of the time.” 80% of US toys now contain an electronic component and tech gadgets are now the Christmas presents of choice – amongst preschoolers!

Is it just a coincidence, I wonder, that Ritalin prescriptions (for attention deficit disorder) have grown by 300% over the last decade?

What I’m getting at here is the thought that we never get a chance to really be by ourselves, which means we never get a chance to really know ourselves. We never get the opportunity to sit quietly and think deeply about who we are and where we are going.

Ironically, this universal connectivity also means that we tend to be alone even when we are together. You can see this when couples go out to dinner and spend most of their time texting – or when kids get together for play-dates and end up sitting next to each other on separate gaming consoles for hours on end. This is what I call Digital Isolation. It is what Sherry Turkle at MIT calls being Alone Together.

What worries me most though is what’s happening to the quality of our thinking, which I believe is becoming shallow, narrow, cursory, fractured and thin.

This is problematic because I firmly believe that originality largely depends on periods of deep thinking. I believe that serious creativity, whether in academia, business or the arts, is dependent on periods of thinking that are calm, concentrated, focused and above all reflective.

Moreover, unless you have been asleep for the last thirty years, you might have noticed that a knowledge revolution has replaced brawn with brains as the primary tool of economic production. It is intellectual capital that now matters. But we are on the cusp of another revolution. Soon, smart machines will compete with clever people for employment and even human affection. Hence being able to think in ways that machines cannot will, I believe, become vitally important.

Put another way, machines are becoming adept at matching stored knowledge to patterns of human behaviour, so we are shifting from a world where people are paid to accumulate and distribute fixed information to one where knowledge will be automated and people will be rewarded instead as conceptual and creative thinkers.

However, there’s a problem. Our education system is still largely designed to produce people that will compete head on with such machines. We are still producing logical and convergent thinking, when what’s often needed, I would argue, is illogical and divergent thinking. In short, we are ignoring one half of our brains.

There is a woman in the US called Lynda Stone who came up with the term Constant Partial Attention to describe how our thinking is becoming fractured and fragmented. My version of this is Constant Partial Stupidity.

We tend not to fully concentrate on one thing nowadays. Instead, we continually scan the digital environment for new information. And we start to believe that we can do more than one thing at once. According to a 2009 US study, multi-tasking is now becoming the normal state. However, the same study found that the people that multi-task the most are in fact the worst at it. Heavy multi-taskers are poor at analysis and forward planning. They also lose the ability to ignore irrelevant data. They are suckers for distraction and become bored when they are not constantly stimulated.

Multi-tasking also means that we are more likely to make silly mistakes, although sometimes mistakes get serious. I don’t know whether you remember Mr de Silva but this was the man that famously used his laptop to get instructions on how to avoid a traffic jam on the M6 motorway. Unfortunately, he was driving a lorry at the time and smashed into a line of cars killing six people.

Such people are not alone in outsourcing their thinking to machines. For example, if you can Google any piece of information more or less instantly why bother learning anything? If a Sat Nav can always tell you where you are why worry about situational awareness or bother to learn how to read a map?

Now it’s true that you can always turn the technology off, but most of us don’t because there is cultural pressure to be constantly available and to instantly respond.

The point here is that it seems to me that we need context as well as text. We need to understand principles before we move on to applications. We need breadth and depth not superficial facts.

Unless we know how things relate to one another we will just have information. For knowledge we need to understand connections. For wisdom we need to understand consequences.

Second, if everyone is using the same sources what of originality? You might think I’m exaggerating about this but I’m not. Far from creating an intellectual paradise, it appears that digitalisation might be narrowing our thinking. For example, 99% of Google searches never proceed beyond page 1 of results and according to a meta-study of academic studies, academic papers are now citing fewer studies not more.

Third, what if one day the technology doesn’t work? What then? We assume, for instance, that the internet will always work. But what if it doesn’t. What if one day the volume of data becomes so great that it becomes blocked? What if energy shortages disrupt access? What if cyber-attacks become such a problem that things move offline? What then?

Why does any of this matter? Who cares if our brains are changing? We’ve always invented new things. We’ve always worried about new things and we’ve always moaned about younger generations. Surely most of what I’m saying is conjecture mashed up with middle-aged technology angst?

I think the answer to this is that it’s a bit different this time. Digital devices are becoming ubiquitous. They are becoming addictive. They are becoming prescribed.

At the moment we have a choice. We can choose paper over pixels. We can choose to talk to a human being rather than a customer service avatar. W can choose to go to go to the library rather than Google.

But what if one day there is no choice. What if all books become e-books? What if all physical libraries are replaced by digital equivalents (or by Google)?

This probably sounds fanciful. But it’s all happening already. Governments and businesses alike are moving everything they can online for the sake of cost or convenience. But I am concerned that while the quantity of communications is increasing exponentially, the quality may be going backwards.

Secondly, and more importantly, people need people. It seems that one by-product of the digital age is that our relationships are becoming more superficial. Thanks to text messages, e-greetings and social networks we know more people but we know them less well. We have replaced intimacy with familiarity.

It is interesting to note that 10 years ago 1 in 10 Americans said they had nobody to confide in. 10 years on and this figure has jumped to 1 in 4.

Now I’m sure I will be accused of exaggerating this point, but it seems to me that empathy and tolerance of others could be two of the casualties of instant digital gratification. If we are constantly looking at a screen, in iPod oblivion as it were, we are less aware of others, some of whom may need our help and some of whom may have something important to say.

Equally, if we are able to personalise our experience of reality via RSS feeds, Google alerts and friendship requests, it is less likely that we will be confronted with ideas or people that challenge the way we think.

The internet is a wonderful invention. I couldn’t do most of what I do today without it. Moreover, I am not declaring war on digital devices. Many of them are extremely useful. Neither am I saying that Google is evil or that Apple is rotten. They are not. I’m just arguing for some level of analogue/digital balance.

I’m saying that we should think further ahead and question some of our assumptions.

Also that technology should be used in combination with human judgement not as a replacement. That we use technology to enhance relationships not to negate them

So what can we do?

The first thing we need to do is think. We need to think about the relative merits of different analogue and digital technologies. For example, evidence is emerging that pixels are different to paper. When we use screens our minds are set on seek and acquire. This is great for the fast accumulation or distribution of facts. But with paper it’s different. Our minds are more relaxed, we tend to see context. Our thinking is more curious and questioning. In short, paper is more absorbent.

Another example. There’s evidence that people are more reckless with money when it’s digitalised. It’s as though it belongs to someone else and we spend it more impulsively. It’s the same, in my experience, with digital statements and bills.We look but we do not see.

Think about this for a second. What if it were proven beyond all reasonable doubt that reading something on a screen is inferior to reading something on paper. Can you imagine how that would impact education? Can you imagine the lobbying that would go on from the likes of Google, Apple, Microsoft and Nokia?

To sum up, I think that if originality and empathy are to survive the onslaught of the digital age we need to do three things.

First, we should restrict the flow of information. In the US, people consumed 300% more information in 2008 than they did in 1960. We should therefore learn how to control the flow of information and remember that not all information is useful or trustworthy. We should also remember that, despite the digital revolution, the medium still influences the message.

The Second thing we should do is disconnect from time to time. Our brains need to relax. If they don’t they can’t function properly. Without rest our memories are not properly stabilised. Moreover, a lack of sleep can inhibit the formation of new brain cells. So switch your mobile off at certain times. It’s interesting to me that we try to set boundaries around screen use for our kids, yet we do not restrict our own usage.

So resist the urge to take your BlackBerry on holiday. Don’t answer texts in restaurants and don’t send emails when you are spending time with your kids.

Most of all, create the time and space to think. When, for instance, was the last time that you told someone that you were going off “to do a bit of thinking.” So go for a walk. Do something that is superficially mundane that allows your mind to wander.

Third, go to places where new ideas can find you. I did some research for my book that asked people where they did their “best thinking.”

Interestingly, not a single person mentioned digital technology. Nobody said, “On the phone”, “On Facebook”, “Twitter” or “Google”. Technology, it seems, is good for developing and disseminating ideas, but not much use for hatching them.

What I also found fascinating was that only one person said in the office, and they said very early in the morning – in other words, when the building wasn’t really functioning as an office at all.

Why don’t people have good ideas at work? The main reason is that they’re too busy. You need to stop thinking before you can have a good idea.

Did any of the answers I received from people about their thinking spaces have anything in common? I think so. Scale seems to be important. You need to feel small. That’s probably why so many people mentioned beaches, mountains and churches. I imagine that great libraries are good too. In such situations our minds seem to expand to fill the available space. Seeing a distant horizon also appears to help in that our thinking is projected forward.

Movement (especially planes, trains and automobiles but also water) is good, as are environments that are slightly restricted or beyond our control (i.e. a long-haul plane trip where you can’t go anywhere). I imagine prisons are quite good too.

Here’s a final thought. The human brain is, as far as we know, the most complex structure in the universe. But it has one simple feature. It is not fixed. It is malleable. It is impressionable to the point where it records every single thing that happens to it.

You might think that text messages and internet searches don’t affect you but you’d be wrong. They already have. The question is therefore not whether they influence your thinking but how.

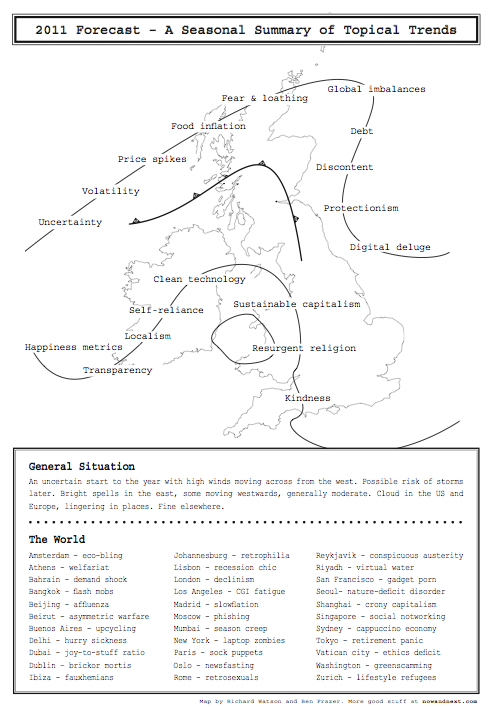

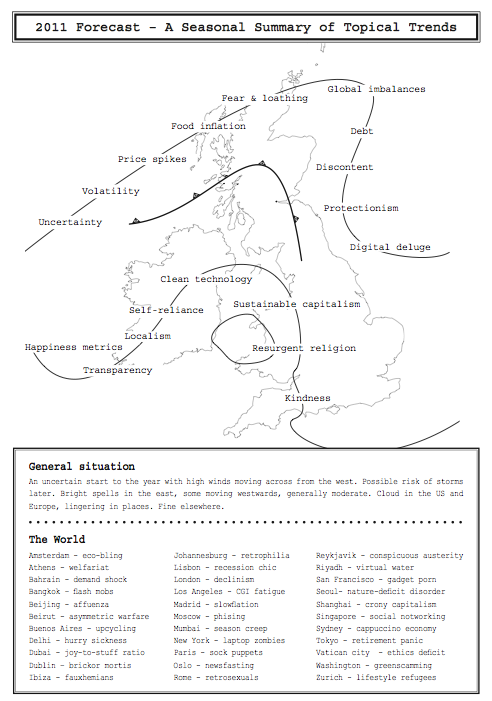

2011 Trend Map

In the words of Saint Bob, the beloved singer-songwriter and social trends observer: “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” Having said that, a little information graphic can’t do any harm. So here’s a new map for my UK readers showing the forecast for 2011. The times, as they say, are a-changin.

I’ll post a URL for this in a few days.

Sci-Fi Hardware Store

Nice to see the new book in Singapore airport. Bumped into the old one in Vancouver airport a few weeks back too. I’ve been thinking (dangerous, I know).

I must have one of the best jobs in the world. I fly around the place talking to interesting people and they send me money. I also get paid just for reading. OK, I have to write too, but that’s not exactly a hardship is it? Anyway, enough nonsense.

I’m a bit busy today writing something on the future of work (again) and thinking about how to do at talk in Oxford without using slides. Also fiddling around with something on scenarios for the future of sport. I did notice that BP have just published their Energy Outlook to 2030 this morning. Google it. It’s quite interesting.

Toying with a gig in South Africa and waiting on a few things in South Korea too. Less about me tomorrow, hopefully. BTW, this is great. Zach from Inventables in the US sent me a link to his hardware store full of sci-fi materials for innovators. It’s brilliant. www.inventables.com/?version=2![photo[189]](http://toptrends.nowandnext.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/photo189.jpg)

Population Trends

The absolute increase in the world’s working age population (i.e. men and women aged 15-64) will be approximately 900 million people over the next 2 decades. Sounds a lot, but the increase over the previous 2 decades was 1.3 billion*. Implications? Assuming an economic recovery, one key consequence will be severe skills shortages with a significant power shift away from the employer to the employee.

* US Census Bureau figures.

Laptops, sandwiches, DIY skills & romantic fiction

A driver in the UK was recently pulled over by police for using a mobile phone and a laptop whilst driving. Police also suspected that the driver might have been eating a sandwich at the same time. Meanwhile, a report in the UK says that DIY skills could be “extinct” by the year 2048 because home maintenance skills are no longer being passed down between generations. In the 1970s 71% of men learnt DIY skills from their dads, now it’s 44%.

Something more serious? OK, I’d predict that romantic novels (i.e. Mills & Boon et al) are going to boom. Why? First, because in times of doom & gloom people need some escapist pleasure with a happy ending. Second, bodice-ripping romance novels are perfect for e-formats. They are quick snacks that do not require deep thinking and the fact that book covers are hidden from view on an e-reader removes the public embarrassment factor. Whether this means that e-readers will encourage authors to write material that’s more pornographic is an interesting question perhaps.

2020 Tax Commission

There’s a group called 2020 Tax Commission looking at how Britain’s tax system should look in the year 2020. All well and good. Except that the commission is made of white, middle aged men, 90% of whom have an economics or tax background. I’m being a bit unfair. There’s one woman.

But seriously folks. Where’s the diversity in terms of age, gender, background, expertise or experience? Here’s a prediction. The group will have lots of meetings and will eventually come up with something that is nothing more than an extended official future.

They may debate a flat tax scenario (a fixed tax percentage for everyone earning more than a certain amount) but I very much doubt they will get as far as discussing a scenario where direct taxation is totally removed in favour of indirect taxation relating to individual (or institutional) behaviour (i.e. you link tax to what people spend or consume rather than linking it to what people earn or save).

Come on guys, shake it up a bit!

http://www.taxpayersalliance.com/2020tc/2011/01/meeting-minds-map-future-tax.html

Thou shalt not blog on Sundays.

Part of my digital diet.

Predictions for the next 25 years

The Observer newspaper recently asked a group of experts for some predictions for what might happen over the next 25 years. Here’s some extracts from the predictions, together with my own comments. Thanks to Bradley who sent me the original link to this article. BTW, the original article came out on 2 January 2011, but many of the predictions refer to the year 2035, which would explain why 2011 + 25 = 2035.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/jan/02/25-predictions-25-years

1 ‘Rivals will take greater risks against the US’

“The 21st century will see technological change on an astonishing scale. It may even transform what it means to be human. But in the short term – the next 20 years – the world will still be dominated by the doings of nation-states and the central issue will be the rise of the east” –Ian Morris (See my post January 14) Professor of history at Stanford University and the author of Why the West Rules – For Now

Comment

I totally agree. And, to quote another author, Michael Mandelbaum, “The one thing worse than an America that is too strong, the world will learn, is an America that is too weak”, However, remember that the US is probably more resilient than many people imagine and China has more problems than many can see. I also agree that while science & technology make for great predictions (and scenarios) the most practical things you can look at are a few key indicators, such as demographics, energy, food and so on – all of which impact nation states.

2 ‘The popular revolt against bankers will become impossible to resist’

“The popular revolt against bankers, their current business model in which neglect of the real economy is embedded and the scale of their bonuses – all to be underwritten by bailouts from taxpayers – will become irresistible.” – Will Hutton, executive vice-chair of the Work Foundation and an Observer columnist

Comment

I came up with the same prediction back in late 2006, so I agree, but I don’t. At the moment this looks certain, but Hutton is making the classic mistake of extrapolating from the present. Banker bashing is a knee-jerk reaction. Moreover, it is too simplistic. What about the people that borrowed the money from the banks? Or what about the fact that interest rates have been at such low levels? For many people things aren’t that bad. I believe that the issue of banks will remain for a short period, but we will become concerned about something else in due course and the issue of bankers and banker bonuses will fade away. Unless, of course, there is indeed a second crisis of similar proportions, in which case things will change (but we will need a bigger crisis to create real shifts).

3 ‘A vaccine will rid the world of Aids’

“We will eradicate malaria, I believe, to the point where there are no human cases reported globally in 2035. We will also have effective means for preventing Aids infection, including a vaccine. With the encouraging results of the RV144 Aids vaccine trial in Thailand, we now know that an Aids vaccine is possible.” – Tachi Yamada, president of the global health programme at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Comment

I don’t know enough about this area to comment, so I won’t.

4 ‘Returning to a world that relies on muscle power is not an option’

“The challenge is to provide sufficient energy while reducing reliance on fossil fuels, which today supply 80% of our energy (in decreasing order of importance, the rest comes from burning biomass and waste, hydro, nuclear and, finally, other renewables, which together contribute less than 1%). Reducing use of fossil fuels is necessary both to avoid serious climate change and in anticipation of a time when scarcity makes them prohibitively expensive….disappointingly, with the present rate of investment in developing and deploying new energy sources, the world will still be powered mainly by fossil fuels in 25 years and will not be prepared to do without them.” – Chris Llewellyn Smith, former director general of Cern and chair of Iter, the world fusion project.

Comment

Bad choice of headline, but I agree with the prediction. In 25 years coal, oil and gas will still produce the vast majority (70-80%) of the world’s energy. Nuclear will be more important in some, but not all, regions. As for renewable energy, the issue is scale. Solar looks promising for some countries, but wind, wave and geothermal just don’t cut it as global solutions in my view. There is the possibility of some ‘magic bullet’ technology, but I think this will only happen when the cost of fossil fuels becomes so great we are forced to really do something.

5 ‘All sorts of things will just be sold in plain packages’

“In 25 years, I bet there’ll be many products we’ll be allowed to buy but not see advertised – the things the government will decide we shouldn’t be consuming because of their impact on healthcare costs or the environment, but that they can’t muster the political will to ban outright. So, we’ll end up with all sorts of products in plain packaging with the product name in a generic typeface-as the government is currently discussing for cigarettes.” – Russell Davies, head of planning at the advertising agency Ogilvy and Mather

Comment

I disagree. There will be more warnings – on everything from alcohol and confectionary to credit cards and cars, but I don’t agree with the plain wrapper theory.

6 ‘We’ll be able to plug information streams directly into the cortex’

“By 2030, we are likely to have developed no-frills brain-machine interfaces, allowing the paralysed to dance in their thought-controlled exoskeleton suits. I sincerely hope we will not still be interfacing with computers via keyboards, one forlorn letter at a time….I’d like to imagine we’ll have robots to do our bidding. But I predicted that 20 years ago, when I was a sanguine boy leaving Star Wars, and the smartest robot we have now is the Roomba vacuum cleaner. So I won’t be surprised if I’m wrong in another 25 years. AI has proved itself an unexpectedly difficult problem.” – David Eagleman, neuroscientist and writer

Comment

Best prediction on the list, not because I necessarily agree with it, but because it’s so provocative (that’s what predictions are for, surely?). Personally, I think this is all highly likely except for the bit about robots and the thought of downloading data directly into your mind – or of uploading your mind into a machine. We will have direct brain-to-machine interfaces (we already do – I’ve got one), which is much the same as mind control. We will ask our computers questions and they will answer back. The mouse and the keyboard will be long gone and machines will have some kind of emotional intelligence (they will know what mood you are in, for instance or they will be programmed to be afraid of doing certain things). However, I believe that the inventions the geeks really want (general AI or the ability to stream data directly into the cortex) are impossible for the foreseeable future.

7 ‘Within a decade, we’ll know what dark matter is’

“The next 25 years will see fundamental advances in our understanding of the underlying structure of matter and of the universe. At the moment, we have successful descriptions of both, but we have open questions. For example, why do particles of matter have mass and what is the dark matter that provides most of the matter in the universe?” – John Ellis, theoretical physicist at Cern and King’s College London

Comment

A 50% chance of this coming true. The real question, the biggest question of them all perhaps, is where we’ll we go from there? Personally, I find the idea of where the galaxies came from and where they (we) are going over the much longer term quite fascinating.

8 ‘Russia will become a global food superpower’

“By the middle of that decade (2035), therefore, we will either all be starving, and fighting wars over resources, or our global food supply will have changed radically. The bitter reality is that it will probably be a mixture of both….in response to increasing prices, some of us may well have reduced our consumption of meat, the raising of which is a notoriously inefficient use of grain. This will probably create a food underclass, surviving on a carb – and fat-heavy diet, while those with money scarf the protein… Russia will become a global food superpower as the same climate change opens up the once frozen and massive Siberian prairie to food production.” – Jay Rayner, TV presenter and the Observer’s food critic

Comment

Disagree. First there are two big assumptions here. The first involves climate change and global warming. Personally, I think one should remain open about some of the predictions on this subject and look at several scenarios, including global cooling.

If cooling were to happen things could look very nasty for Russia. Second, I think the timescale of 2036 is too short for this prediction and, third, Russia has some other issues, especially demography and health, to focus on before they worry about becoming a food superpower. BTW, Rayner says population will be nudging 9 billion by 2035. I think that could be wrong. I think it’s 2050.

9 ‘Privacy will be a quaint obsession’

“Some, like the futurist Ray Kurzweil, predict that nanotechnology will lead to a revolution, allowing us to make any kind of product for virtually nothing; to have computers so powerful that they will surpass human intelligence; and to lead to a new kind of medicine on a sub-cellular level that will allow us to abolish ageing and death…I don’t think that Kurzweil’s “technological singularity” – a dream of scientific transcendence that echoes older visions of religious apocalypse – will happen. Some stubborn physics stands between us and “the rapture of the nerds”. But nanotech will lead to some genuinely transformative applications. “- Richard Jones, pro-vice-chancellor for research and innovation at the University of Sheffield

Comment

I don’t see the relationship here between the prediction (the headline) and the text of the story. Yes, nanotech has privacy implications, but they are nothing compared to what the internet is doing – or possibly genetics. Do I agree with the prediction about privacy being deleted? I haven’t made my mind up yet.

10 Gaming: ‘We’ll play games to solve problems’

“In the last decade, in the US and Europe but particularly in south-east Asia, we have witnessed a flight into virtual worlds, with people playing games such as Second Life. But over the course of the next 25 years, that flight will be successfully reversed, not because we’re going to spend less time playing games, but because games and virtual worlds are going to become more closely connected to reality.” – Jane McGonigal, director of games research & development at the Institute for the Future in California

Comment

I agree (but taken too far I don’t like the idea)

11 ‘Quantum computing is the future’

“The open web created by idealist geeks, hippies and academics, who believed in the free and generative flow of knowledge, is being overrun by a web that is safer, more controlled and commercial, created by problem-solving pragmatists. Henry Ford worked out how to make money by making products people wanted to own and buy for themselves. Mark Zuckerberg and Steve Jobs are working out how to make money from allowing people to share, on their terms… By 2035, the web, as a single space largely made up of webpages accessed on computers, will be long gone… and by 2035 we will be talking about the coming of quantum computing, which will take us beyond the world of binary, digital computing, on and off, black and white, 0s and 1s.” – Charles Leadbeater, author and social entrepreneur.

Comment

I don’t think this is saying very much.

12 Fashion: ‘Technology creates smarter clothes’

“Technology is already being used to create clothing that fits better and is smarter; it is able to transmit a degree of information back to you. This is partly driven by customer demand and the desire to know where clothing comes from – so we’ll see tags on garments that tell you where every part of it was made, and some of this, I suspect, will be legislation-driven, too, for similar reasons, particularly as resources become scarcer and it becomes increasingly important to recognise water and carbon footprints.” – Dilys Williams, designer and the director for sustainable fashion at the London College of Fashion

Comment

Define smart? I see a polarization between high-tech fashion (wearable computers, smart fabrics, global brands) and sustainable clothing (often locally sourced and highly functional).

13 Nature: ‘We’ll redefine the wild’

“I’m confident that the charismatic mega fauna and flora will mostly still persist in 2035, but they will be increasingly restricted to highly managed and protected areas….. Increasingly, we won’t be living as a part of nature but alongside it, and we’ll have redefined what we mean by the wild and wilderness…Crucially, we are still rapidly losing overall biodiversity, including soil micro-organisms, plankton in the oceans, pollinators and the remaining tropical and temperate forests. These underpin productive soils, clean water, climate regulation and disease-resistance. We take these vital services from biodiversity and ecosystems for granted, treat them recklessly and don’t include them in any kind of national accounting.” – Georgina Mace, professor of conservation science and director of the Natural Environment Research Council’s Centre for Population Biology, Imperial College London

Comment

Sounds perfectly reasonable to me.

14 Architecture: What constitutes a ‘city’ will change

“In 2035, most of humanity will live in favelas. This will not be entirely wonderful, as many people will live in very poor housing, but it will have its good side. It will mean that cities will consist of series of small units organised, at best, by the people who know what is best for themselves and, at worst, by local crime bosses…Cities will be too big and complex for any single power to understand and manage them. They already are, in fact. The word “city” will lose some of its meaning: it will make less and less sense to describe agglomerations of tens of millions of people as if they were one place, with one identity. If current dreams of urban agriculture come true, the distinction between town and country will blur.” – Rowan Moore, Observer architecture correspondent

Comment

Urban agriculture is pure fantasy in my view, especially vertical farming. I agree that in 25 years most people will probably live in poor housing but it will probably be an improvement on what people lived in 25 years ago.

Most people will definitely live in cities, but I suspect that with the exception of a handful of iconic individual buildings, office complexes and retail developments, most people will continue to live in what we, living in 2011, would immediately recognize as cities.

15 Sport: ‘Broadcasts will use holograms’

“Globalisation in sport will continue: it’s a trend we’ve seen by the choice of Rio for the 2016 Olympics and Qatar for the 2022 World Cup. This will mean changes to traditional sporting calendars in recognition of the demands of climate and time zones across the planet…Sport will have to respond to new technologies, the speed at which we process information and apparent reductions in attention span. Shorter formats, such as Twenty20 cricket and rugby sevens, could aid the development of traditional sports in new territories.” – Mike Lee, chairman of Vero Communications and ex-director of communications for London’s 2012 Olympic bid.

Comment

I am just about to start work looking at the future of sport so it’s a bit early to really comment on this one. Yes, the globalization of sport will probably continue but we should not underestimate counter-trends (e.g. local or ‘real football’ as an alternative to global football brands with mega-budgets). Yes to new technologies too and I certainly agree with short format sport as a reaction to shorter attention spans (Golf is next for the short-format treatment apparently).

16 Transport: ‘There will be more automated cars’

“It’s not difficult to predict how our transport infrastructure will look in 25 years’ time – it can take decades to construct a high-speed rail line or a motorway, so we know now what’s in store. But there will be radical changes in how we think about transport. The technology of information and communication networks is changing rapidly and internet and mobile developments are helping make our journeys more seamless. Queues at St Pancras station or Heathrow airport when the infrastructure can’t cope for whatever reason should become a thing of the past.” – Frank Kelly, professor of the mathematics of systems at Cambridge University.

Comment

Agree with the first bit, but good luck with the point about queues and seamless journeys. First, I think he could be overestimating the impact of technology and secondly (more importantly) he is neglecting economics. In the West especially governments are burdened by debt and rising urban populations and it’s quite possible that much public infrastucture will be in very poor repair by 2036.

17 Health: ‘We’ll feel less healthy’

“Health systems are generally quite conservative. That’s why the more radical forecasts of the recent past haven’t quite materialised. Contrary to past predictions, we don’t carry smart cards packed with health data; most treatments aren’t genetically tailored; and health tourism to Bangalore remains low. But for all that, health is set to undergo a slow but steady revolution. Life expectancy is rising about three months each year, but we’ll feel less healthy, partly because we’ll be more aware of the many things that are, or could be, going wrong, and partly because more of us will be living with a long-term condition.” – Geoff Mulgan, chief executive of the Young Foundation

Comment

Agreed.

18 Religion: ‘Secularists will flatter to deceive’

“Organised religions will increasingly work together to counter what they see as greater threats to their interests – creeping agnosticism and secularity… I predict an increase in debate around the tension between a secular agenda which says it is merely seeking to remove religious privilege, end discrimination and separate church and state, and organised orthodox religion which counterclaims that this would amount to driving religious voices from the public square.” – Dr Evan Harris, author of a secularist manifesto

Comment

Fascinating subject (I’d love to do some scenarios on the future of religion). I agree with some of this. I think that the world will become more religious over the next 25 years but the idea that secularization will grow is potentially suspect.

19 Theatre: ‘Cuts could force a new political fringe’

“Student marches will become more frequent and this mobilisation may breed a more politicised generation of theatre artists. We will see old forms from the 1960s re-emerge (like agit prop) and new forms will be generated to communicate ideology and politics.” – Katie Mitchell, theatre director.

Comment

Disagree. Yes, I this could happen, but I think a much stronger trend could be quite the opposite. If the economy (in the West) fails to pick up and we enter a prolonged period of doom and gloom, I would predict that people will get so sick and fed up that sugary, escapist, nostalgic fantasies and musicals with thrive.

20 Storytelling: ‘Eventually there’ll be a Twitter classic’

“Twenty-five years from now, we’ll be reading fewer books for pleasure. But authors shouldn’t fret too much; e-readers will make it easier to impulse-buy books at 4am even if we never read past the first 100 pages…My guess is that, in 2035, stories will be ubiquitous. There’ll be a tube-based soap opera to tune your iPod to during your commute, a tale (incorporating on-sale brands) to enjoy via augmented reality in the supermarket. Your employer will bribe you with stories to focus on your job. Most won’t be great, but then most of everything isn’t great – and eventually there’ll be a Twitter-based classic.” – Naomi Alderman, novelist and games writer

Comment

I’d predict that in 25 years Twitter won’t exist (and I’ll take a bet on that).