“It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to”

- Jean-Luc Godard.

“It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to”

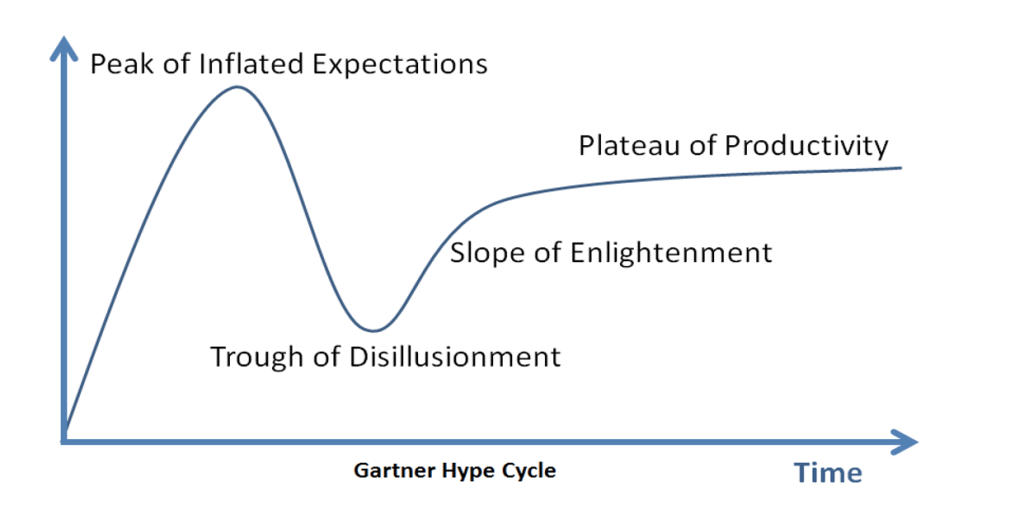

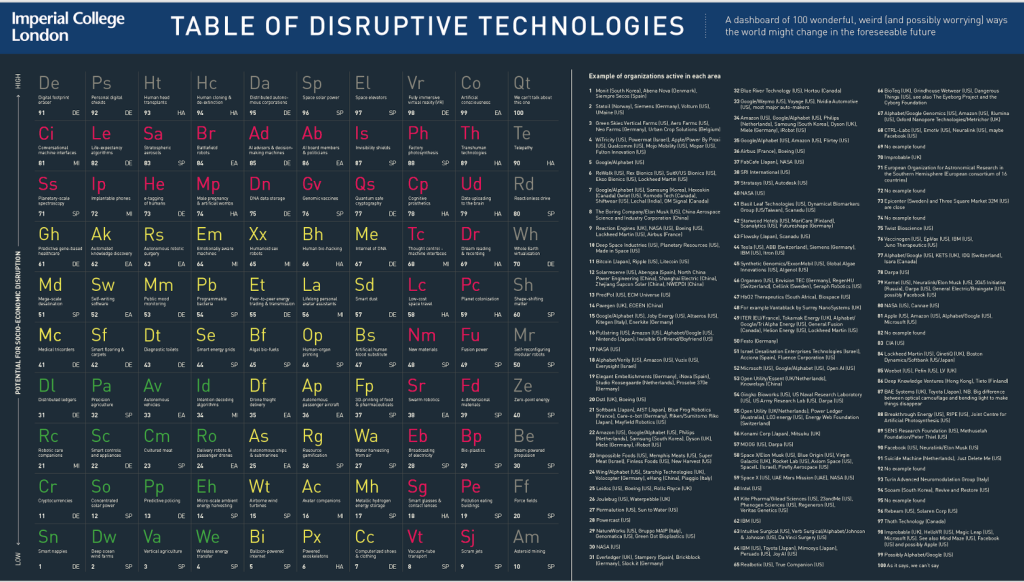

Where have I been? LinkedIn mainly. I will try to be here more often in the future. Much to post, but let’s start with this article about when innovations succeeed – or fall flat. Best read having looked at Gartner’s Hype Cycle and my own Table of Disruptive Terchnologies.

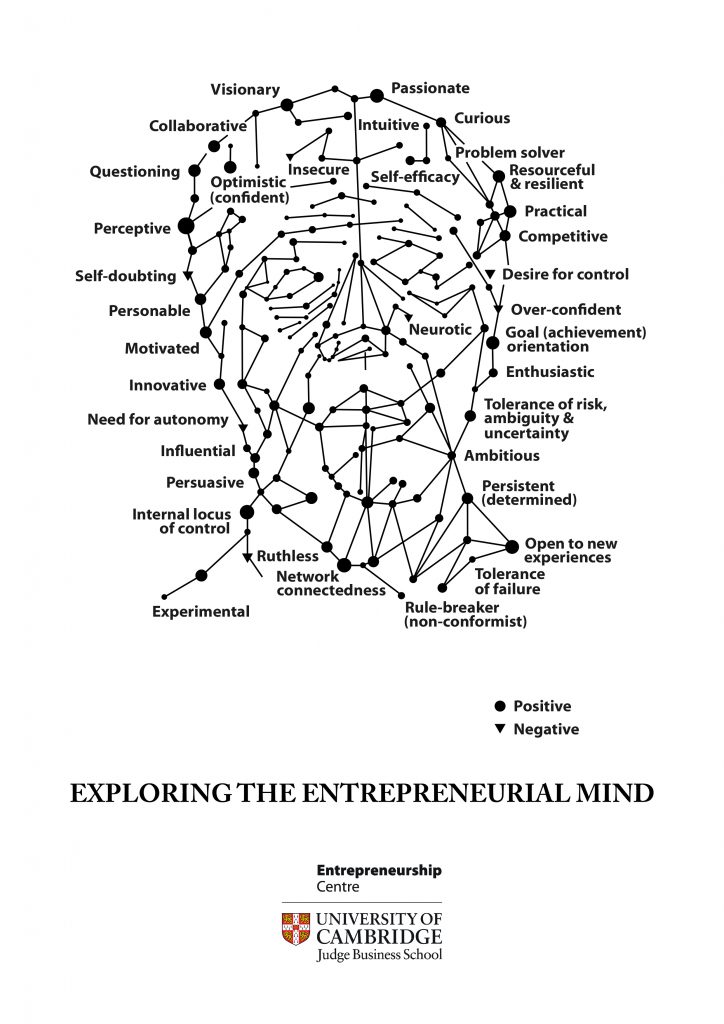

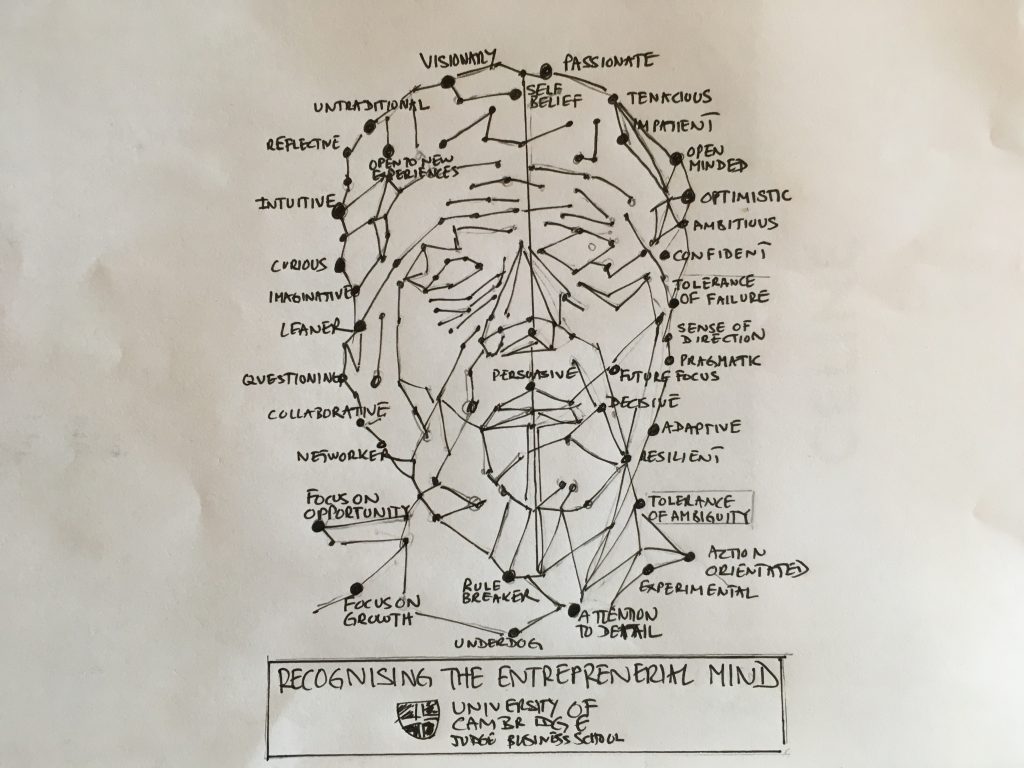

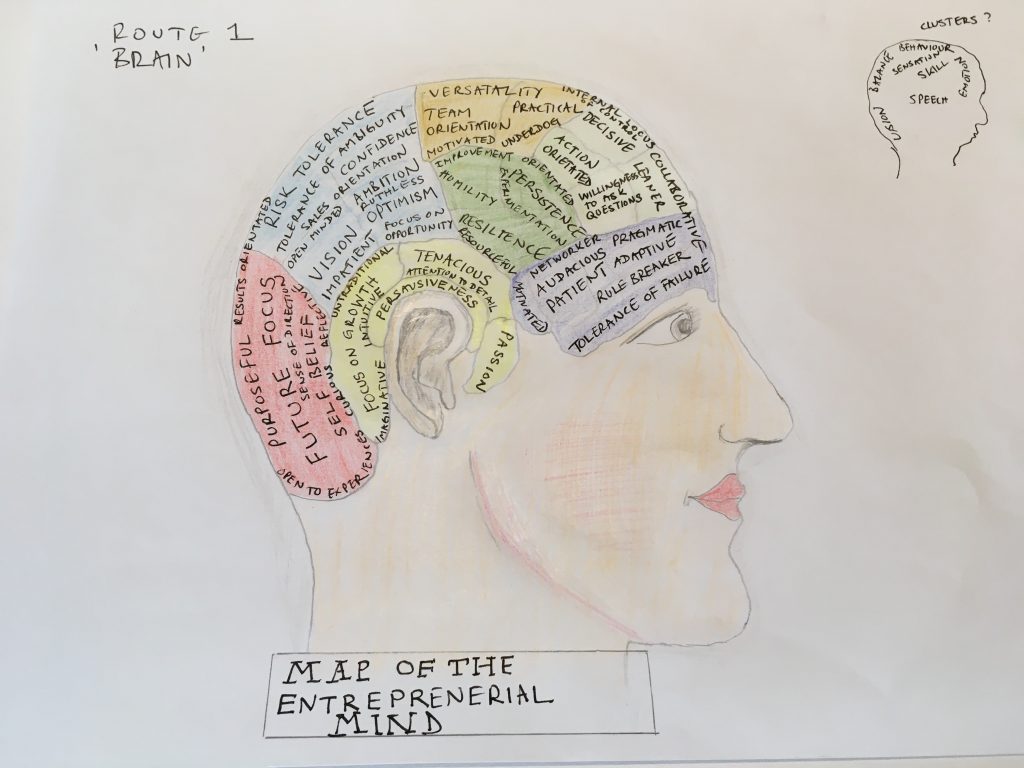

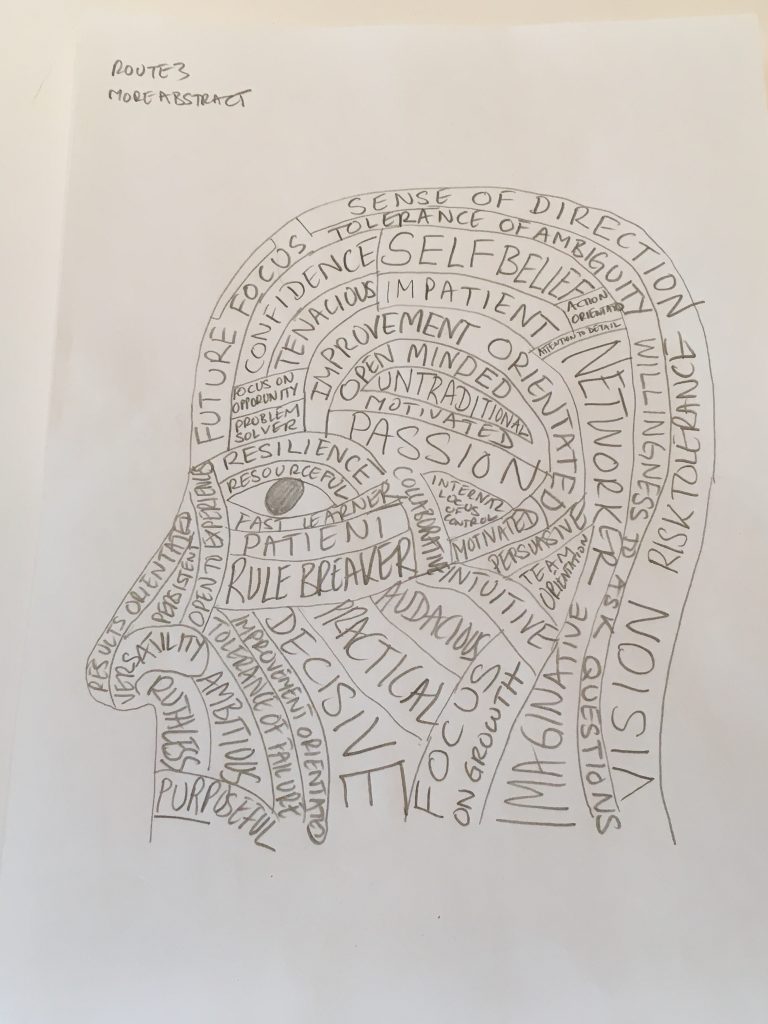

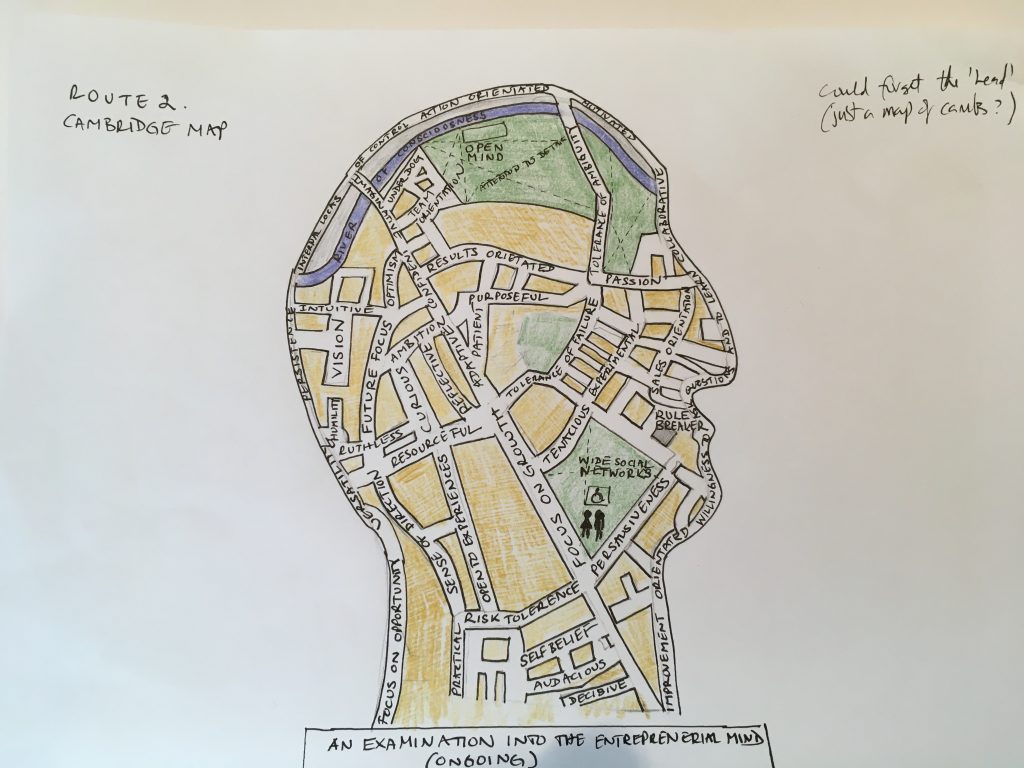

This one has been a while coming. It’s a visual exploration of some of the traits and states associated with an entreprenerial mind. Obviously not everyone will possess all of these traits or states and neither are they static – these will change over time too as a start-up grows and new people join the business. Perhaps a question is which states work best throughout an organisations lifecycle?

Bibliography:

Peta Levi, ‘Flourishing in the Cambridge parkland’, Financial Times, November 1980

Segal Quince Wicksteed, The Cambridge Phenomenon: The Growth of High Technology Industry in a University Town, 1985

Lyle M. and Signe M. Spencer, Competence at work: models for superior performance (Chapter 17, Entrepreneurs), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1993

Sally Caird, What do psychological tests suggest about entrepreneurs? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 8(6) pp. 11–20, 1993

Tom Byers (Stanford), Heleen Kist (Stanford) and Robert I. Sutton (Hass), Characteristics of the Entrepreneur: Social Creatures, Not Solo Heroes, Handbook of Technology Management, Richard C. Dorf (Ed), CRC Press, October 1997

Yin M. Myint, Shailendra Vyakarnam and Mary J. New, The effect of social capital in new venture creation: the Cambridge high‐technology cluster, John Wiley & Sons, June 2005

S Kavadias, SC Sommer, The effects of problem structure and team diversity on brainstorming effectiveness, Management Science, 2009

T Miller, M Grimes, J McMullen and T Vogus, Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship, Academy of Management Review 37 (4), 616-640, 2012

J Hutchison‐Krupat, RO Chao, Tolerance for failure and incentives for collaborative innovation, Production and Operations Management, 2014

The Cambridge Phenomenon: 50 Years of Innovation and Enterprise, Kate Kirk and Charles Cotton, Third Millennium, 2012

M. Frese & M. M. Gielnik, The psychology of entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 413–438, 2014

M. J. Gorgievski & U. Stephan, Advancing the Psychology of Entrepreneurship: A Review of the Psychological Literature and an Introduction. Applied Psychology, 65(3), 437–468, 2016

Lynda Applegate, Janet Kraus, and Timothy Butler, Skills and Behaviors that Make Entrepreneurs Successful, HBR Working Knowledge, June 2016

Dean A. Shepherd and Holger Patzelt, Entrepreneurial Cognition: Exploring the Mindset of Entrepreneurs, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018

Nicos Nicolaou, Phillip H. Phan and Ute Stephan, The Biological Perspective in Entrepreneurship Research, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, November 2020

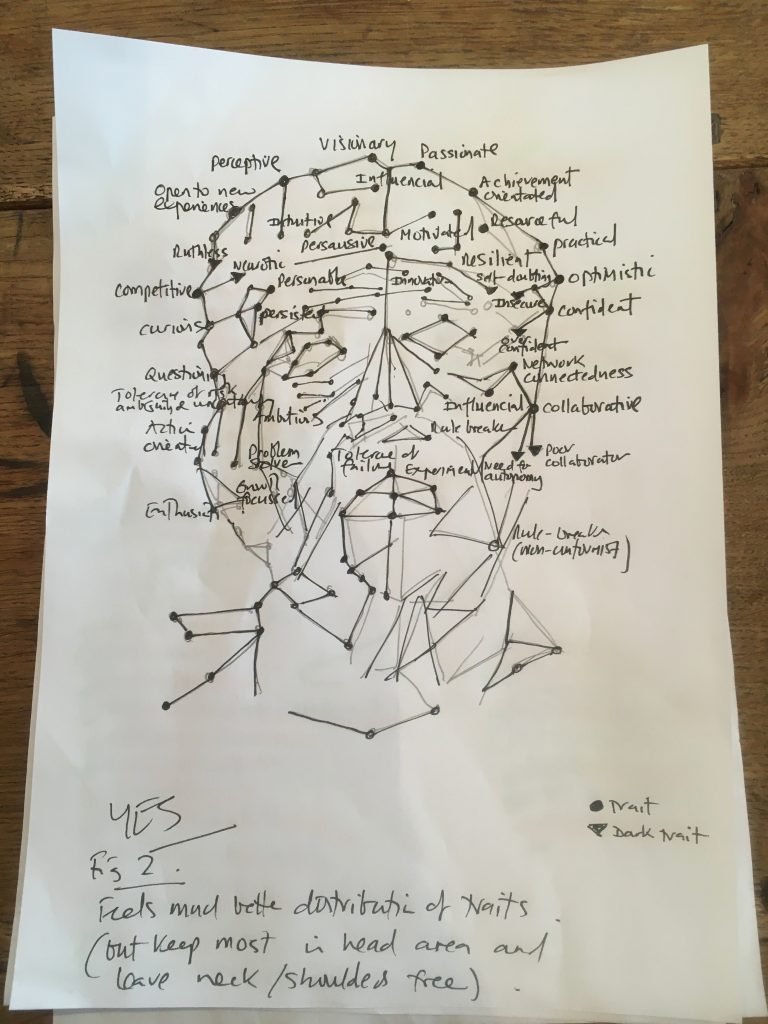

Early roughs…

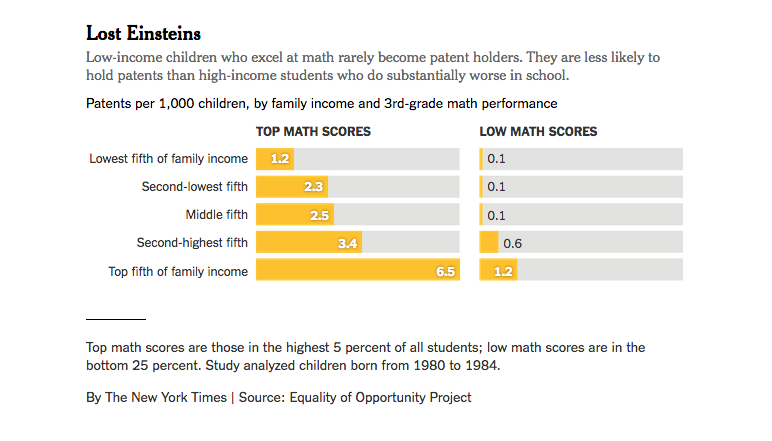

Funny how two words can be so powerful. An article in the New York Times about a Stanford study looking at what influences potential Einsteins. This graph below concerns income, other graphs look at race and gender. Thanks for Chris at Nesta who mentioned this to me.

I’m in Oman speaking at a technology conference organised by Bank Muscat. But here’s the thing. I was doing some background homework on Oman, especially on the future of Oman. This got me looking at a project called Oman 2040 (also mentioned at the conference). Looking into this further I got into future skills and education (a subject very close to my heart – my mother was a teacher). Anyway, quite separately I’m supposed to be writing something on the future of universities for publication in Australia (I get around!). I’ve been stuck on this for weeks to the point where I was about to say that I couldn’t do it. But then two things happened (and I think this is how ideas hatch generally, which links to innovation and, serendipitously, another conference in Oman called the Global Innovation Summit. (Stay with me here it’s going somewhere).

Last week I was at another conference on AI at Cambridge (like I said, I get around). By total fluke I sat next to a film maker at dinner. (I tried to sit next to a few other people, but they told me to move!). Anyway, the film maker and I got talking about education and he mentioned the 4-Cs of education (Critical thinking, Communication, Collaboration and Creativity). So that idea got stuck in my subconscious.

Then today I was having dinner by myself in Muscat and after eating I had a cigar (known as a ‘thinking stick’ to a salesman from IBM that I once met). Then out of nowhere I had an idea. The 4C’s are all wrong*. It should be the Seven Cs. They should be: Collaboration, Creativity, Critical Thinking, Communication, Curiosity, Compassion (EQ) and (Moral) Character.

So, there you have it folks. That’s how ideas get born. My essay on the future of universities is now flowing like there’s no tomorrow…

Can biology teach us anything about innovation? The essence of Darwinism is that progress is created by adaptation to changing circumstances. What starts off as a random mutation often spreads throughout a population to eventually become the norm through a process of natural selection. The same is surely true with innovation. New ideas are mutations created through chaos and adaptation, especially when two or more old ideas combine or reproduce in unusual or unexpected ways. In short, innovation = inheritance (history) + variation + selection.

Serendipity clearly plays an important part in this process and the list of things created by accident is certainly impressive; Aspirin, Band-Aids, credit cards, DNA finger printing, dynamite, inoculation, Jell-O, Ferrari, Lamborghini, microwave ovens, penicillin, ink-jet printers, X-rays, nylon, heart pacemakers, Coca-Cola, Teflon, Vulcanised rubber, Nintendo, Lego, Smart Dust, matches, dynamite (yikes), safety glass, Corn Flakes, Super Glue, Viagra and Velcro to name quite a few.

Pursuing experiments – and tolerating the inevitable failures that result – is therefore one practical way to make an organisation more innovative. But is there is another option? Is there a strategy, process or even a culture that will embed innovative thinking at the very core of an organisation’s being? I think there is.

Think about when individuals and institutions are at their most innovative. You might think about the cross-fertilisation of disciplines and experience. This is indeed one way to kick-start innovative thinking and it’s not that difficult to design spaces where diverse people will bump into each other in a random manner. Office kitchens and staircases immediately spring to mind. Lunch is even better. A Harvard Business Review article once claimed that P&G had attempted to “systemise the serendipity” that so often sparks innovation. When the Hollywood producer Brian Grazer heard about this he commented: “that’s what we call lunch.”

Another route is to combine the energy and naivety of youth with the wisdom and cynicism of old age. This can work too. Reverse mentoring is a very practical idea championed by the likes of former GE boss Jack Welsh. Or there’s the thought of recruiting both the newest and the oldest members of staff for brainstorms. Diversity in terms of skills is key, but so too are age and experience.

And, of course, there’s the idea that if you generate enough ideas one will surely be good enough to use. This does occasionally work, although in my experience not very often. I prefer the opposite, which involves thinking inside a small box rather than thinking outside of one. Read, for example, Adam Morgan’s book called A Beautiful Constraint.*

So, what’s my big idea for generating big ideas? What’s my million- dollar idea? Death. That’s right, demise, departure, disappearance, extinction, the grim reaper. Hold on, am I seriously suggesting that we kill companies and organisations just to reinvent them?

Sort of.

It strikes me that true clarity only arrives occasionally and generally it’s when we think we are going to die. If we are looking down the barrel of a gun – or a microscope – we tend to see our death (and with it our entire life) in high definition. This creates a tremendous sense of urgency to put it mildly. This might not be of much use if we have seconds to live, but if we are given weeks or months we’re often able to focus on the things we really want to do and separate what’s merely urgent from what’s actually important. Relationships are rekindled, ideas are hatched, things get reinvented.

Sometimes we are fortunate. We think we are going to die, but we don’t. The tests or the analysis were wrong. The threat failed to materialise. We were lucky. Sometimes the change resulting from serious threats is enduring, although more often than not we revert to our bad old ways once the grim reaper has gone elsewhere. This is true for institutions as much as it’s true for individuals.

One of the reasons that Apple, sometimes cited as the world’s most valuable company, is so innovative might be to do with the fact it was 90 days away from being bankrupt back in 1997. Similar near death experiences abound, ranging from Telsa, SpaceX and KFC to Airbnb, FedEx and IBM.

So, the second million-dollar question must surely be this…can you fake your own death in order to think straight or to become more innovative? Believe it or not a company in South Korea once tried to do precisely this, although it backfired somewhat.

Back in 2008 there was a South Korean craze called ‘well-dying’ in which employees would write and then read out their last words in fake funeral services. Organisations such as Samsung and Hyundai sent their employees on courses organised by Korea Life Consulting in order to question their life paths and priorities. The idea got a lot of bad press at the time, partly because people were required to get inside a real coffin, but it wasn’t a wholly bad idea.

Asking people what they’d do if they had a day, a week or a year left to live can be a good way to reveal what they really think about things, including themselves. Asking a leadership team inside a large organisation to do the same is a similarly good way to reveal not only priorities, but potentially to revaluate strategies too. What might you do differently if you didn’t have to worry about regulation, unions, governments, quarterly earnings and so forth?

After all, if you have absolutely nothing to lose you will behave very differently than if you do. You will try things that are riskier and be far less concerned with what others might think of you. In short, you will be brave and be led by your heart as much as your head. You’ll dream big and be less inclined to get stuck on practicalities.And, of course, we only truly appreciate what we have been given when there’s a real chance that these same things will be taken away. It is only through death that we really learn to live.

As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Try using a narrative of rapidly changing circumstances and ultimately the imminent extinction of your organisation to radically revaluate where you are going and how you might get there.Or write an obituary for your organisation and then treat it as a strategy for reincarnation.

Carpe diem.

* A Beautiful Constraint: How to transfer your limitations into advantages, and why it’s everyone’s business by Adam Morgan

Can biology teach us anything about innovation? The essence of Darwinism is that progress is created by adaptation to changing circumstances. What starts off as a random mutation often spreads throughout a population to eventually become the norm through a process of natural selection. The same is surely true with innovation. New ideas are mutations created through chaos and adaptation, especially when two or more old ideas combine or reproduce in unusual or unexpected ways.

Serendipity clearly plays an important part in this process and the list of things created by accident is certainly impressive; Aspirin, Band-Aids, credit cards, DNA finger printing, dynamite, inoculation, Jell-O, Ferrari, Lamborghini, microwave ovens, penicillin, ink-jet printers, X-rays, nylon, heart pacemakers, Coca-Cola, Teflon, Vulcanised rubber, Nintendo, Lego, Smart Dust, matches, dynamite (yikes), safety glass, Corn Flakes, Super Glue, Viagra and Velcro to name quite a few.

Pursuing experiments – and tolerating the inevitable failures that result – is therefore one practical way to make an organisation more innovative. But is there is another option? Is there a strategy, process or even a culture that will embed innovative thinking at the very core of an organisation’s being? I think there is.

Think about when individuals and institutions are at their most innovative. You might think about the cross-fertilisation of disciplines and experience. This is indeed one way to kick-start innovative thinking and it’s not that difficult to design spaces where diverse people will bump into each other in a random manner. Office kitchens and staircases immediately spring to mind. Lunch is even better. A Harvard Business Review article once claimed that P&G had attempted to “systemise the serendipity” that so often sparks innovation. When the Hollywood producer Brian Grazer heard about this he commented: “that’s what we call lunch.”

Another route is to combine the energy and naivety of youth with the wisdom and cynicism of old age. This can work too. Reverse mentoring is a very practical idea championed by the likes of former GE boss Jack Welsh. Or there’s the thought of recruiting both the newest and the oldest members of staff for brainstorms. Diversity in terms of skills is key, but so too are age and experience.

And, of course, there’s the idea that if you generate enough ideas one will surely be good enough to use. This does occasionally work, although in my experience not very often. I prefer the opposite, which involves thinking inside a small box rather than thinking outside of one. Read, for example, Adam Morgan’s book called A Beautiful Constraint.*

So, what’s my big idea for generating big ideas? What’s my million- dollar idea? Death. That’s right, demise, departure, disappearance, extinction, the grim reaper. Hold on, am I seriously suggesting that we kill companies and organisations just to reinvent them?

Sort of.

It strikes me that true clarity only arrives occasionally and generally it’s when we think we are going to die. If we are looking down the barrel of a gun – or a microscope – we tend to see our death (and with it our entire life) in high definition. This creates a tremendous sense of urgency to put it mildly. This might not be of much use if we have seconds to live, but if we are given weeks or months we’re often able to focus on the things we really want to do and separate what’s merely urgent from what’s actually important. Relationships are rekindled, ideas are hatched, things get reinvented.

Sometimes we are fortunate. We think we are going to die, but we don’t. The tests or the analysis were wrong. The threat failed to materialise. We were lucky. Sometimes the change resulting from serious threats is enduring, although more often than not we revert to our bad old ways once the grim reaper has gone elsewhere. This is true for institutions as much as it’s true for individuals.

One of the reasons that Apple, sometimes cited as the world’s most valuable company, is so innovative might be to do with the fact it was 90 days away from being bankrupt back in 1997. Similar near death experiences abound, ranging from Telsa, SpaceX and KFC to Airbnb, FedEx and IBM.

So, the second million-dollar question must surely be this…can you fake your own death in order to think straight or to become more innovative? Believe it or not a company in South Korea once tried to do precisely this, although it backfired somewhat.

Back in 2008 there was a South Korean craze called ‘well-dying’ in which employees would write and then read out their last words in fake funeral services. Organisations such as Samsung and Hyundai sent their employees on courses organised by Korea Life Consulting in order to question their life paths and priorities. The idea got a lot of bad press at the time, partly because people were required to get inside a real coffin, but it wasn’t a wholly bad idea.

Asking people what they’d do if they had a day, a week or a year left to live can be a good way to reveal what they really think about things, including themselves. Asking a leadership team inside a large organisation to do the same is a similarly good way to reveal not only priorities, but potentially to revaluate strategies too. What might you do differently if you didn’t have to worry about regulation, unions, governments, quarterly earnings and so forth?

After all, if you have absolutely nothing to lose you will behave very differently than if you do. You will try things that are riskier and be far less concerned with what others might think of you. In short, you will be brave and be led by your heart as much as your head. You’ll dream big and be less inclined to get stuck on practicalities.And, of course, we only truly appreciate what we have been given when there’s a real chance that these same things will be taken away. It is only through death that we really learn to live.

As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Try using a narrative of rapidly changing circumstances and ultimately the imminent extinction of your organisation to radically revaluate where you are going and how you might get there.

Write an obituary for your organisation and then treat it as a strategy for reincarnation.

Carpe diem.

* A Beautiful Constraint: How to transfer your limitations into advantages, and why it’s everyone’s business by Adam Morgan