1). Everyday acceleration.

People are spending more time online and are increasingly ‘always on.’ I even heard a father recently say that his teen now exists in one of two states: “Asleep or online”.

Add to this the impact of globalisation (markets that never close), the fact that it’s becoming easier to do anything, anywhere (24/7 mobile access to many goods and services) and corporate downsizing (more than one job to do) and you end up with a culture of rapid response, hectic households and people with not enough hours in the day to do everything they think needs doing.

Implications?

A demand for speed and convenience, an interest in filtering and currated consumption (because there’s now too little time and too much choice), multi-tasking (the erroneous belief that we can do more than one thing at once well), more mistakes (trying to do too much plus an increasing amount of distraction means getting more things wrong), less rigorous thinking (no time for reflection), less sleep, more anxiety and, ironically, a growing interest in trying to slow things down.

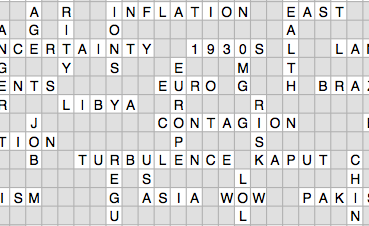

Another consequence is what’s been termed information pandemics. The idea here is that in the olden days (15-20 years ago) it took a long time for news to circulate. Therefore, individuals and institutions had time to properly consider whether threats were real or not and had the time to devise rigorous responses. Nowadays things circulate so fast (and people believe that they have so little time to react) that responses are often badly formulated or misjudged. The precautionary principle in politics, and society in general, fans this attitude of overreaction.

2). Data deluge

It’s become far too easy (and cheap) to create and distribute news and information.

The result is that everyone is now doing it and one consequence of this is a data deluge, with much of this news and information being of questionable origins or value.

This is atomising our attention, but is also making our relationships with individuals and institutions wafer thin and, at times, short-term.

Implications.

We need to adjust our mindset away from the old idea that information is power. Nowadays it’s primarily attention that’s power and we need to better understand that not all material is useful or trustworthy. We need to create better filters for information and learn to ignore what’s not useful, whilst being careful not to shut out things that may become useful over time. In short, we need to slow a few things down, either by switching things off from time to time or by deliberately using certain channels or media depending on what it is that we are trying to achieve.

Expect to see more interest in filtering, digests, data visualisation and reputation scores and reliability metrics.

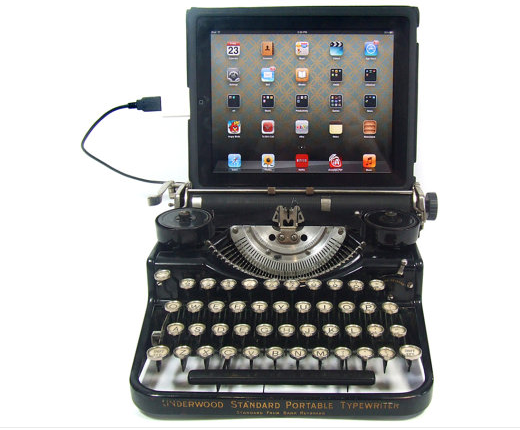

3). Image & Text

We are entering a period where the power of the image is rising at the expense of the written word. This is largely demand driven – a reaction to people being time starved – but it’s also being driven by the supply side. The internet started off as a text-based medium and is now largely image driven, with video being a key component. Meanwhile, graphic novels are booming and telecom companies are reporting a massive increase in text-based communication at the expense of voice communications.

Implications?

Tensions in education with students demanding short, sensory and highly interactive instruction. Also, a danger of misunderstandings created by the lack of tonality and body-language contained within text-based communications. Also a growing demand for data visualisation and information aesthetics.

4). Online Anonymity

They say the things you love about someone when you start a relationship are the things you hate by the end of it. Our relationship with the internet has, until now, largely depended on anonymity. But the problems of anonymity are growing, such as lying, fraud, cyber bullying, or just outright bad behaviour and even hate. People behave differently online because they are anonymous. There are no real consequences.

Facebook and Google have started to change this. You have to use your real name to log on and everything you do is traced back to your real offline identity. This means your life becomes much more public and to some extent true, although my own experience of people using Facebook, especially with younger people, is that what they say is happening online is far from what is true in reality.

Implications

In the short-term expect to see more virtual courage and online hostility. Whether such nastiness, hatred and negativity flows out into the real world is an interesting debate.

Over the longer-term I suspect that online anonymity will go, although this point is open to discussion, along with the question of whether or not the generative nature of the internet will one day disappear, replaced by what is effectively a series of locked-down regional intranets (i.e. Apple owns Wikipedia, the information contained therein is fixed and can only be accessed by Apple products).

5) Transparency & Privacy

This is interesting because it both supports and contradicts the previous point.

On the one had digital information + connectivity means that things that were previously hidden, or only available to the eyes and ears of a few, is now open for all to see and hear. This is a good thing on one level because it fuels honesty and promotes collaboration and possibly empathy. But the corresponding trend is a decline in privacy, which not only includes what people say or see, but also where people are, what they are doing, what they are buying, whom they know and even what they think.

At the moment there are generational differences in terms of the response to this. Generation Y and below are generally unconcerned, although this can cause trouble. Generation X are concerned, but are not sure what can be done and Baby Boomers are generally blissfully ignorant of what’s occurring.

Implications

More honesty and accountability, but also more cyber and physical crime. Over time I’d expect our reactions to move towards the centre, with people becoming more aware of the dangers of over-sharing or placing information in certain formats or channels. Equally, calls for transparency will settle somewhere that’s realistic and practical and benefits the needs of all concerned.

6). Personalisation

One of the great things about digitalisation is that material can be personalised by users, often to the needs of a single individual. This can mean customising content generally or it might mean the customisation of content based upon precisely where someone is at a particular moment (i.e. locational services). However, there is a darker side to this. If we all, increasingly, live inside personalised bubbles of information, there’s a danger that we will become less tolerant of others, because we will not have our views or ideas challenged. A culture based on ‘me’ isn’t good for empathy or understanding of others.

Implications

More satisfaction and enjoyment on one level, but more selfish behaviour and intolerance on another, at least until society’s values and legislation catch up with the new technology.

7) Collaboration & Ownership

On one level, digital culture seems to be driving people apart, fuelling both isolation, passivity and self-importance. On another level, connectivity is bringing people together and is driving creativity and cooperation. We now, arguably, have a greater understanding of what’s going on much further away and we are more aware of the problems facing the world. Connectivity also means that it’s easier to find like-minded individuals and it appears that we are discovering that things we once assumed needed to be owned by in individual can in fact be shared by all, once we find something, or someone, we can trust. (i.e. Zipcar and iCloud being early examples of collaborative consumption and dematerialisation).

Implications

A realisation that none of us are as smart as all of us, a shift away from individual ownership towards shared or collaborative consumption and experiences.