I’m just playing around with these thoughts. Any comments for or against would be most welcome.

There was a report in a newspaper a while ago about a mother whose six-year-old had asked her whether he should put a slice of bread in the toaster “landscape or portrait?” I mentioned this to my ten-year-old son and he said: “He should have Googled it.”

I mention this because I am interested in how spaces and places change how we think. In particular I am interested in how new digital objects and environments are starting to change age-old attitudes and behaviours, including how we relate to one another.

And this directly leads me to a very particular place, namely public libraries and the question of whether or not they have a future. In short, what is the role – or value- of public libraries and public librarians in an age of e-books and Google?

Now at this point I have to put my hand up and admit to being wrong. Some time ago I created an extinction timeline, because I believe that the future is as much about things we’re familiar disappearing as it is about new things being invented. And, of course, I put libraries on the extinction timeline because, in an age of e-books and Google who needs them.

Big mistake. Especially when one day you make a presentation to a room full of librarians and show them the extinction timeline. I got roughly the same reaction as I got from a Belgian after he noticed that I’d put his country down as expired by 2025.

Fortunately most librarians have a sense of humour, as well as keen eyesight, so I ended up developing some scenarios for the future of public libraries and I now repent. I got it totally wrong. Probably.

Whether or not we will want libraries in the future I cannot say, but I can categorically state we will need them, because libraries aren’t just about the books they contain. Moreover, it is a big mistake, in my view, to confuse the future of books or publishing with the future of public libraries. They are not the same thing.

Let’s start by considering what a public library is for. Traditionally the answer would have been a place to borrow books. This is where the argument that libraries are now dying or will soon be dead originates. After all, if you can download any book in 60-seconds, buy cheap books from a supermarket or instantly search for any fact, image or utterance on Google why bother with a dusty local library?

I’d say the answer to this is that public libraries are important because of a word that’s been largely ignored or forgotten and that word is Public. Public libraries are about more than mere facts, information or ‘content’. Public libraries are places where local people and ideas come together. They are spaces, local gathering places, where people exchange knowledge, wisdom, insight and, most importantly of all, human dignity.

A good local library is not just about borrowing books or storing physical artefacts. It is where individuals become card-carrying members of a local community. They are places where people give as well as receive.

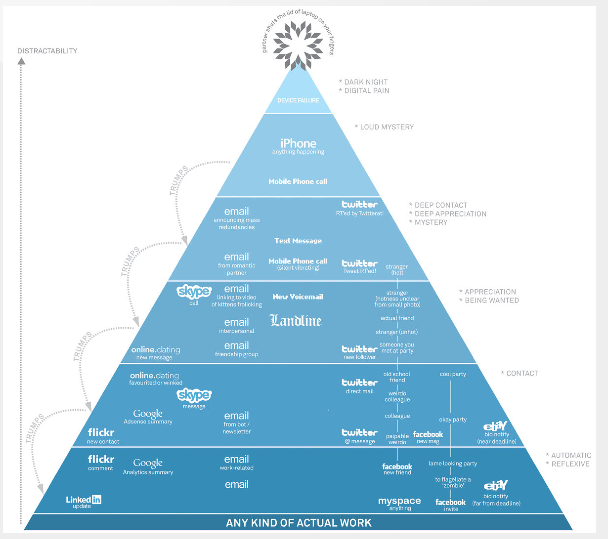

Libraries are keystones delivering the building blocks of social cohesion, especially for the very young and the very old. They are where individuals come to sit quietly and think, free from the distractions of our digital age. They are where people come to ask for help in finding things, especially themselves. And the fact that they largely do this for nothing is nothing short of a miracle.

It is interesting to me that so much is made of the fact that most things on the internet are free. Indeed whole books have been written on the subject of this radical new price. But the idea of free information is nothing new and when free public libraries were invented the idea was even more radical because of the high cost of books.

Of course, there is the argument that virtualisation means that we will no longer need public libraries – or that if they continue to exist their services will be tailored to the individual and they will be capable of instantly sending whatever it is that we, as individuals, want direct to the digital device of our choosing. And perhaps some libraries will do this for a fee rather than for free.

Costly mistake. This would be a huge error in my view, partly because what people want is not always the same as what they need and partly because this focuses purely on the information at the expense of overall learning and experience.

Some people have argued that content is now king and that the vessel that houses information is irrelevant. I disagree. I believe that how information is delivered influences the message and is, in some instances, more meaningful than the message.

As I’ve already said, libraries are about people, not just books, and librarians are about more than just saying “Shhh.” They are also about saying: “Psst – have a look at this.” They are sifters, guides and co-creators of human connection. Most of all they are cultural curators, not of paper, but of human history and ideas.

In a world cluttered with too much instant opinion and we need good librarians more than ever. Not just to find a popular book, but to recommend an obscure or original one. Not only to find events but to invent them. The internet can do this too, of course, but it can’t look you in the eye and smile gently whilst it does it.

And in a world that’s becoming faster, noisier, more virtual and more connected, I think we need the slowness, quietness, physical presence and disconnection that libraries provide, even if all we end up doing in one is using a free computer.

Public libraries are about access and equality. They are open to all and do not judge a book by its cover any more than they judge a readers worth by the clothes they wear. They are one of the few free public spaces that we have left and they are among the most valuable, sometimes because of the things they contain, but more usually because of what they don’t.

Of course, we could put a Starbucks into every library – and we could allow mobile phone use and piped music throughout too – but then surely what we will be left with are more global outposts of Starbucks not local libraries.

What libraries do contain, and should continue to contain in my view, includes mother and toddler reading groups, computer classes for seniors, language lessons for recently arrived immigrants, family history workshops and shelter for the homeless and the abused. Equally, libraries should continue to work alongside local schools, local prisons and local hospitals and provide access to a wide range of e-services, especially for people with mental or physical disabilities.

In short, if libraries cease to exist, we will have to re-invent them.

Now, admittedly many younger people still see no need to visit a library. Many, if not most, will not have done so in years. But this could be because they still see libraries as spaces full of old books rather than places full of new ideas.

But this may change. In my view it is inevitable that the ongoing digitalisation of culture will lead to an ever-greater integration of cultural institutions and public libraries will shift from being book places to places that curate our cultural and intellectual heritage. Libraries will thus become memory institution like art galleries and museums. Indeed, why not physically combine all three?

This, of course, means that the role of librarians will change. The idea of professional librarianship will fade and in its place will emerge the idea of professional informational and cultural curators and this will embrace a variety of different skills.

But let’s bring it back to why the physical space that libraries occupy is so important. Again, libraries are not important because they contain books per se. They are, in my view, important because of how a place full of books make people feel. Great libraries, like all great buildings, change how you feel and this, in turn, changes how you think.

So what’s my idea here? Two thoughts. The first is that we should accept that a library without books would still a library because it would continue to be an important community resource – a neutral public space – where serendipitous encounters with people and ideas take place. This, surely, is an idea worth spreading.

My second idea is that we should consider funding libraries in new and novel ways. This could mean libraries going back to their philanthropic roots and asking wealthy individuals to buy or build libraries rather than football clubs or art galleries.

Or it could mean getting governments to impose taxes on certain leisure pursuits that are known to provide no mental nourishment or social cohesion and use the revenue generated to subsidise other, more useful, things like public libraries or good books.

There is a considerable amount of discussion at the moment about obesity. The idea that we should watch what we eat or we will end up prematurely dead. But where is the debate about the quality of what and where we read or write? Surely what we put inside our heads – where we create or consume information – is just as important as what we put inside our mouths.