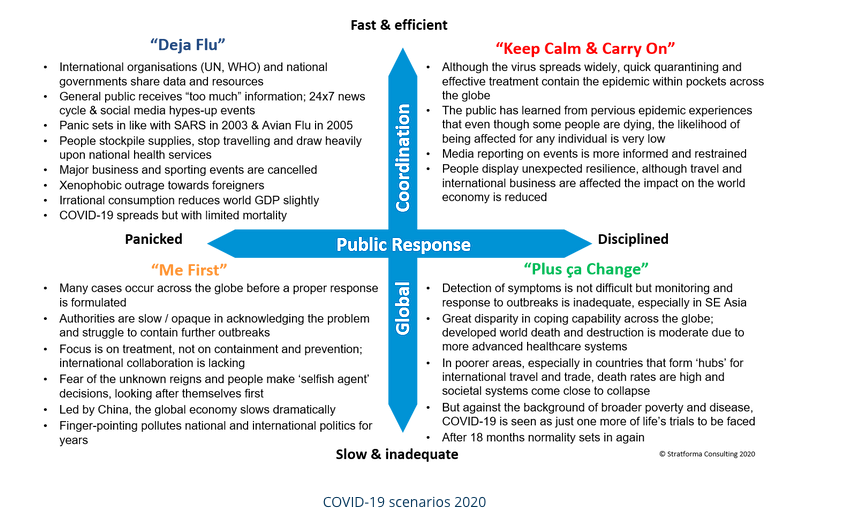

A scenario matrix from my friend Nick Turner at Stratforma. His explanation below.

The framework is built on the axes of two critical uncertainties:

- The nature of global coordination; “slow and inadequate” vs. “fast and efficient”

- The nature of public response; “panicked” vs. “disciplined”

When placed in a 2×2 matrix, four scenarios unfold:

“Déjà Flu”: a world where despite national governments and multi national agencies responding in a responsible and coordinated fashion, feed “too much” information, the public over-react, resulting in irrational consumption and even xenophobic outrage.

“Keep Calm & Carry On”: a world where the virus spreads but effective quarantining and treatment contain the epidemic and the public display unexpected resilience, as the media behave in a more retrained way.

“Plus ça Change”: a world of disparity in response across the globe between developed and developing economies, the population of latter, despite experiencing high mortality rates, shrug off as just another one life’s challenges to be faced.

“Me First”: a world of delay, opacity, incompetence and unpreparedness, leading to public panic, overreaction and selfishness, the after effects of which linger for years.

More on this in Nick’s post here.