Category Archives: Digital culture

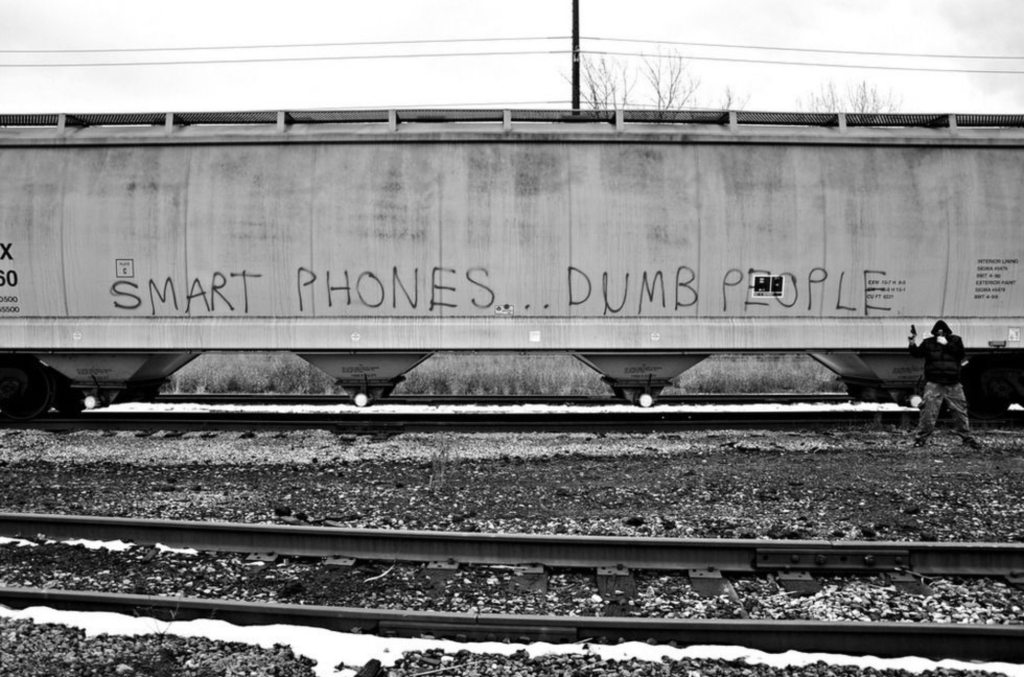

Look up, not down!

People preferring company of screens to people

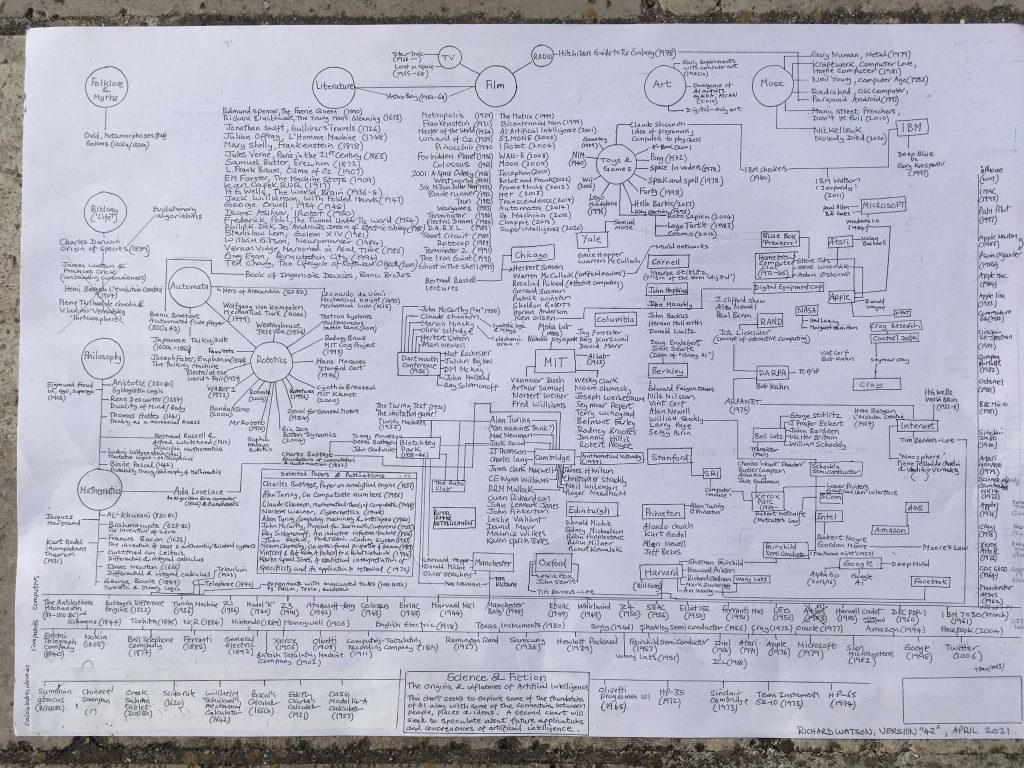

Back to the Future of AI

I think I’m getting somewhere with this. I often find that before looking forwards at the future of something, artificial intelligence, for example, it’s often worth going backwards to the start of things. This is a draft of a visual looking at the history and influences of computing and AI.

It needs a sense check, contains errors and is somewhat western-centric, but then I am all of these things. It’s also very male-heavy, but then that was the world back then – and in AI and IT possibly still is. Perhaps I should do a visual showing women in AI – starting with women at Bletchley Park, NASA and so on. I may spin this off into a series of specific maps looking purely at robotics or software too.

Digital technology and carbon emissions

I was at the Web Summit last week in Lisbon. I’ve never seen quite so many black North Face rucksacks in one place, although black faces were almost totally absent. OK, there was some refreshing energy and optimism, but also quite a bit of delusion (in my opinion) surrounding future AI and the inevitability of conscious machines.

But the best bit was, without doubt, the sustainable merchandise. Hand-knitted jumpers for £800 and re-useable drink containers. Heaven forbid that any of the 70,000 attendees used a single use coffee cup. These, of course, were all sold alongside the fact that tech uses around 15-20 per cent of global energy (depending on whom you believe) and has a carbon footprint that would put BP and Boeing to shame (See a good article on the carbon footprint of AI here).

Clearly any industry will create emissions, especially during any transition to clean energy, but what gets my goat is how certain groups and individuals have focussed on one area (e.g. flying) at the total exclusion of others. For example, emissions from the global fashion industry and textile industries match and possibly exceed aviation.

BTW, if anyone has a reliable figure for carbon emissions created by Apple, Facebook and Uber et al – but especially Google and Amazon (incl. AWS) please share!

The continued deletion of people

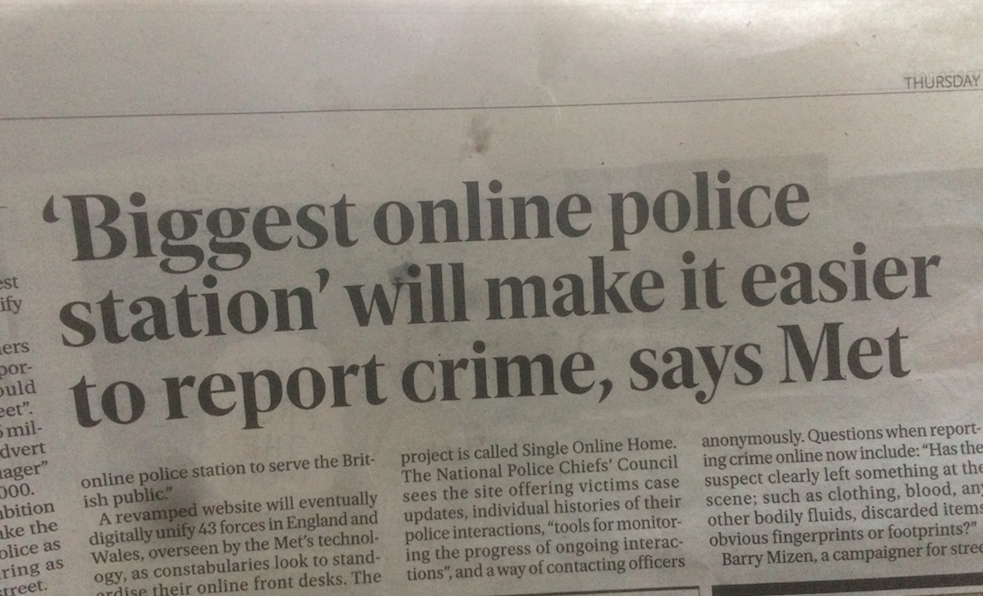

I know I’m not supposed to be reading newspapers, but when I find one left on a train I sometimes flick through.

Anyway, I’m getting increasing concerned by the removal of people. First it was the supermarket (and what a sterile, soulless, joyless place that now is), then it was my bank (no cashiers now, just terminals, with one overworked person with an iPad endlessly explaining to people over the age of 40 (you know, the ones with all the money) why they now have to deal with machines rather than human beings. Above is the latest example.

In theory this might be a good idea. Another channel to contact the police. But we all know what’s going to happen. Mission Creep. It will save the Met a load of money and will eventually be the only way you can contact the police. God forbid your phone gets lost or runs out of battery. And how exactly is an online police station going to provide empathy or reassurance?

Digital Afterlives

“The first time I texted James I was, frankly a little nervous. “How are you doing?” I typed, for want of a better question. “I’m doing alright, thanks for asking.” That was last month. By then James had been dead for almost eight months.” *

“The first time I texted James I was, frankly a little nervous. “How are you doing?” I typed, for want of a better question. “I’m doing alright, thanks for asking.” That was last month. By then James had been dead for almost eight months.” *

Once you died and you were gone. There was no in-between, no netherworld, no underworld. There could be a gravestone or an inscription on a park bench. Perhaps some fading photographs, a few letters or physical mementoes. In rare instances, you might leave behind a time capsule for future generations to discover.

That was yesterday. Today, more and more, your dead-self inhabits a technological twilight zone – a world that is neither fully virtual nor totally artificial. The dead, in short, are coming back to life and there could be hordes of them living in our houses and following us wherever we go in the future. The only question is whether or not we will choose to communicate with them.

Nowadays, if you’ve ever been online, you will likely leave a collection of tweets, posts, timelines, photographs, videos and perhaps voice recordings. But even these digital footprints may appear quaint in the more distant future. Why might this be so? The answer is a duality of demographic trends and technological advances. Let’s start with the demographics.

The children of the revolution are starting to die. The baby boomers that grew up in the shadows of the Second World War are fading fast and next up it’s the turn of those who grew up in the 1950s and 60s. These were the children that challenged authority and tore down barriers and norms. Numerically, there are a lot of this generation and what they did in life they are starting to do in death.They are challenging what happens to them and how they are remembered.

Traditional funerals, all cost, formality and morbidity are therefore being replaced with low-cost funerals, direct cremations, woodland burials and colourful parties. We are also starting to experience experiments concerning what is left behind, instances of which can be a little ‘trippy’.

If you die now, and especially if you’ve been a heavy user of social media, a vast legacy remains – or at least it does while the tech companies are still interested in you. Facebook pages persist after death. In fact going out a few decades there could be more people that are dead on Facebook than the living. Already, memorial pages can be set up (depending on privacy settings and legacy contacts) allowing friends and family to continue to post. Dead people even get birthday wishes and in some instances a form of competitive mourning kicks in. Interestingly, some posts to dead people even become quite confessional, presumably because some people think conversations with the dead are private. In the future, we might even see a kind of YouTube of the dead.

But things have started to get much weirder. James, cited earlier, is indeed departed, but his legacy has been a computer program that’s woven together countless hours of recordings made by James and turned into a ‘bot – but a ‘bot you can natter to as though James were still alive. This is not as unusual as you might think.

When 32-year-old Roman Mazurenko was killed by a car, his friend Eugenia Kuyda memorialised him as a chatbot. She asked friends and family to share old messages and fed them into a neural network built by developers at her AI start-up called Replika. You can buy him – or at least what his digital approximation has become – on Apple’s app store. Similarly, Eter9 is a social network that uses AI to learn from its users and create virtual selves, called “counterparts”, that mimic the user and lives on after they die. Or there’s Eterni.me, which scrapes interactions on social media to build up a digital approximation that knows what you “liked” on Facebook and perhaps knows what you’d still like if you weren’t dead.

This might make you think twice about leaving Alexa and other virtual assistants permanently on for the rest of your life. What exactly might the likes of Amazon, Apple and Google be doing with all that data? Life enhancing? Maybe. But maybe death defying too. More ambitious still are attempts to extract our daily thoughts directly from our brains, rather than scavenging our digital footprints. So far, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have been used to restore motor control in paralysed patients through surgically implanted electrodes, but one day BCIs may be used alongside non-invasive techniques to literally record and store what’s in our heads and, by implication, what’s inside the heads of others. Still not Sci-Fi enough for you? Well how about never dying in the first place?

We’ve seen significant progress in extending human lifespans over the last couple of centuries, although longevity has plateaued of late and may even fall in the future due to diet and sedentary lifestyles. Enter regenerative medicine, which has a quasi-philosophical and semi-religious activist wing called Transhumanism. Transhumanism seeks to end death altogether. One way to do this might be via Nano-bots injected into the blood (reminiscent of the 1966 sci-fi movie Fantastic Voyage). Or we might generically engineer future generations or ourselves, possibly adding ‘repair patches’ that reverse the molecular and cellular damage much in the same way that we ‘patch’ buggy computer code.

Maybe we should leave Transhumanism on the slab for the time being. Nevertheless, we do urgently need to decide how the digital afterlife industry is regulated. For example, should digital remains be treated with the same level of respect as physical remains? Should there should be laws relating to digital exhumation and what of the legal status of replicants? For instance, if our voices are being preserved who, if anyone, should be allowed access to our voice files and could commercial use of an auditory likeness ever be allowed?

At the Oxford Internet Institute, Carl Öhman studies the ethics of such situations. He points out that over the next 30-years, around 3 billion people will die. Most of these people will leave their digital remains in the hands of technology companies, who may be tempted to monetise these ‘assets.’ Given the recent history of privacy and security ‘outages’ from the likes of Facebook we should be concerned.

One of the threads running through the hit TV series Black Mirror is the idea of people living on after they’re dead. There’s also the idea that in the future we may be able to digitally share and store physical sensations. In one episode called ‘Black Museum’, for example, a prisoner on death row signs over the rights to his digital self, and is resurrected after his execution as a fully conscious hologram that visitors to the museum can torture. Or there’s an episode called ‘Be Right Back’ where a woman subscribes to a service that uses the online history of her dead fiancé to create a ‘bot that echoes his personality. But what starts off as a simple text-messaging app evolves into a sophisticated voicebot and is eventually embodied in a fully lifelike, look-a-like, robot replica.

Pure fantasy? We should perhaps be careful what we wish for. The terms and conditions of the Replika app mentioned earlier contain a somewhat chilling passage: People signing up to the service agree to “a perpetual, irrevocable, licence to copy, display, upload, perform, distribute, store, modify and otherwise use your user content.’ That’s a future you they are talking about. Sleep well.

* The Telegraph magazine (UK) 19 January 2019. ‘This young man died in April. So how did our writer have a conversation with him last month?’

Digital Emissions

We hear a lot about the environmental costs of air travel. Burning jet fuel currently contributes around 2.5% to total carbon emissions. Therefore, fly less or stop flying altogether we’re told. But what you don’t hear so much about is that Information Communication Technology (ICT) will be responsible for 3.5% of global emissions by 2020. A 2013 study suggested that the digital economy uses 10% of global electricity and this could double to 20% by 2025. The issue is data centres, but even an iPhone uses more power than a fridge. Tweet that.

PS – On a slightly related note, did you know that bitcoin mining consumes more power than Switzerland?

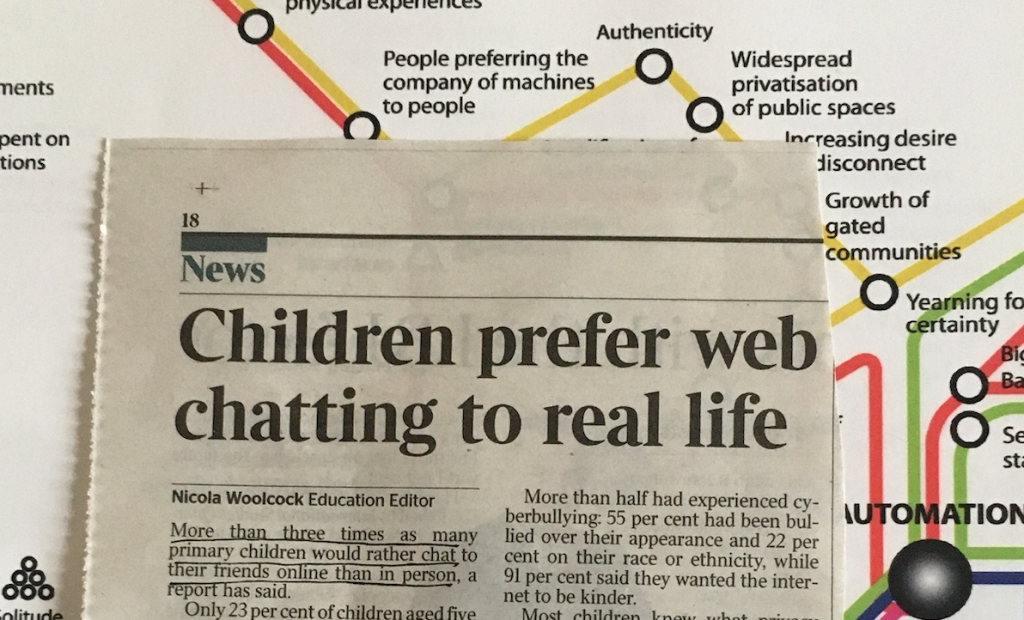

Children and screen use

On the day that a major study has found that using the internet alters our brains, in particular reducing our ability to focus, this article has been published by Dr Aric Sigman in the journal Pediatric Research.

Erring on the wrong side of precaution – Dr Eric Sigman.

Children’s screen media habits are embedded early and last for decades and probably for life. By the time the average American child finishes their 8th year, they will have spent more than a full year of 24-h days on recreational screen time. Shaping their screen media habits in a positive direction from an early stage is therefore imperative.

At a time when discretionary (non-homework) screen time (DST) is the single main activity of First World children, medical bodies from WHO to the US, Australian and New Zealand Departments of Health to the American Academy of Pediatrics and Canadian Pediatric Society increasingly offer parents recommended DST limits as a sensible precautionary measure while research continues. The paper by Pagani et al. and the lead author’s previous work reports ‘developmental persistence in how youth invest their discretionary time’ but adds a new dimension: screen location in early years predicts higher DST and significantly less favourable health and developmental outcomes years later and concludes that ‘This research supports a strong stance for parental guidelines on availability and accessibility.’

Yet on the journey to societal awareness, these public health messages are often met with various calculated obstructions. Parents, including health professionals, are often informed about children and DST through mainstream media, social media, blogs and free online encyclopedias where the issue is often portrayed as an ongoing ‘hotly debated’ cultural issue reflecting a clash between generations, with accompanying headlines such as ‘Screen Time: Is it good or bad for our kids?’.

The Times recently informed the British public that the ‘mental health risk of screens’ for teenagers is no greater than ‘eating potatoes’, explaining that medical concerns are based on ‘cherry-picking of vague research that throws up spurious correlations’.

The New York Times Health section asks ‘But surely screen addiction is somehow bad for the brain?’ and immediately answers ‘It’s probably both bad and good for the brain’, reassuring parents that because they watched hours of TV a day themselves as youngsters, ‘their experiences may be more similar to their children’s than they know’.

The BBC has just informed Britain ‘Worry less about children’s screen use, parents told. There is little evidence screen use for children is harmful in itself, guidance from leading paediatricians says’.

It is worth pointing out that, uniquely, information about the association between DST and paediatric health is increasingly controlled by and accessed through the very media being studied. Screen media often presents itself as a mere neutral platform through which to access information; however, it is worth considering, for example, that BBC Worldwide generates $1.4 billion in ‘Headline’ sales annually from its screen-based products and services. Furthermore, it is almost entirely unheard of for journalists or media to reveal that a DST health study being reported on in the news often emanates from an institution with significant funding from well-known screen media corporations including Google and Facebook.

There are more concerted overtures to influence public and professional perception of this health issue and prevent or discredit precautionary guidance. In 2017, a group of 81 predominantly British and American academic psychologists, including notable luminaries, were so ‘deeply concerned’ about the prospect of British Government health authorities merely offering loose precautionary guidance to parents on excessive child DST that they signed an open letter published in a national newspaper read by many doctors, urging Government doctors not to do so because it would be on the basis of ‘little to no evidence’ that ‘risks’… ‘potentially harmful policies’. Guidelines for parents should be ‘built on evidence, not hyperbole and opinion’.

The Research Director of the Digital Media and Learning Hub, University of California, has attacked the APA’s ‘killjoy ‘screen time’ rules that had deprived countless kids’, lamenting ‘but damage has been done.’

Such debate and conflicting stories may be good for news and social media, drawing the eye to contrariness. However, this is undermining ongoing initiatives to raise awareness among parents that excessive DST is an evolving health issue and to encourage and support them in limiting their children’s excess and late night use.

The purported justification for refraining from offering precautionary DST guidelines is a lack of evidence-based decision-making. Moreover, we are informed most of the evidence is correlational, some of the effect sizes are small, some findings are inconclusive, therefore precautionary guidelines are premature and unjustified.

This point of view appeals to our belief in the impartiality of science and preference for evidence-based decision-making, whereby any precautionary paediatric guidance is ‘grounded in robust research evidence’: systematic reviews of longitudinal randomised controlled studies.

We would all like to have the luxury of formulating public health guidance on the basis of comprehensive neatly quantified data from prospective randomised controlled trials. And it is frustrating to find that the study of DST does not conform to that of other more established areas of paediatric public health.

However, this copious popular refrain ‘evidence-based’ reported in the media is an entirely disingenuous misappropriation of the entire concept of evidence-based medicine. When it comes to policy-making and guidance on child health, the established position remains ‘an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure’. For example, WHO considers the precautionary principle ‘a guiding principle… for WHO and everyone engaged in public health’.

There are times in paediatric public health/preventive medicine when the luxury of ‘robust research evidence’ is not yet available. Moreover, as Pagani et al.’s study design makes clear, DST is obviously not a pharmaceutical substance but a complex, multi-factorial lifestyle behaviour.2 Therefore, producing definitive proof of causation in the many domains of study, from neurobiology to psycho-social, will be a long time coming.

And this is where the calculated obstructions come in to play. As WHO observes, ‘The precautionary principle is occasionally portrayed as contradicting the tenets of sound science and as being inconsistent with the norms of “evidence-based” decision-making… these critiques are often based on a misunderstanding of science and the precautionary principle… people must humbly acknowledge that science has limitations in dealing with the complexity of the real world… thus, there is no contradiction between pursuing scientific progress and taking precautionary action.’

Positioning themselves as standard-bearers of high empiricism, those opposed to offering precautionary DST guidance have appropriated the term ‘evidence-based’ in an attempt to mislead society into thinking that to selectively highlight research findings of unfavourable associations between screen misuse and health outcomes and err on the side of the precautionary principle while research continues is a form of unprofessional ‘cherrypicking’ of the evidence. It implies an attempt at public deception through the intentional omission of unsupportive evidence. Misutilitising the term ‘evidence-based’ is a move to misportray those erring on the side of precaution as employing lower empirical standards, and to those unfamiliar with the precautionary principle and standard protocols in paediatric public health—the public and most media—this may seem a convincing exorcism of shoddy practice. It certainly makes for provocative, entertaining media.

This media carnival, in essence, leaves the AAP, the US, Australian and New Zealand Departments of Health, and WHO among others, along with the authors of many highly respected studies conducted at highly respected institutions published in highly reputable journals, as incompetent, untrustworthy and unprofessional. It wrongly casts them as ignoring the intellectual and social benefits of screen technology and preventing children from ‘exploring the world around them’ and developing their full potential.

Such a position indicates either a profound misunderstanding or the intentional obfuscation of the relationship between science and the precautionary principle, and a high disregard for the experience and clinical judgement of child health professionals.

Those opposed to offering precautionary DST guidance have wilfully avoided the distinction between in-house empirical arguments between scientists versus the routine need to develop responsible general protective health guidance for children. They have misappropriated and emphasised the obvious limitations of existing research as a way of casting doubt on the entire public health issue and on the credibility of those simply advocating moderation and sensible precaution, in the hope that DST guidelines will be perceived as impetuous and premature scaremongering. We are urged to err on the wrong side of caution.

However, rigidly adhering to an abstract principle of high empiricism, with a distorted interpretation of evidence-based medicine taking precedence over the protection of children’s health, should be considered self-indulgent and medically unethical. Furthermore, it reveals a high disregard for the important role of the experience and judgement of child health professionals to interpret available evidence, and promotes a hubristic picture of psychology and ‘educational technology’ researchers knowing better than the many paediatric and public health professionals what is best for protecting child health.

The burden of ‘proof’ must now be on them to demonstrate that high and/or premature exposure to DST—and now bedroom screens—pose no health and development risks to children. The time has come for health professionals to begin to scrutinise the motives of those attempting to obstruct provisional guidance on child DST. They are violating the precautionary principle. Fortunately, research teams such Pagani et al continue to uphold it by addressing the elephant in the room—the overlooked issue of how the mere location of a screen may potentiate greater DST and attenuate necessary developmental experiences. We should follow their advice.

Robots that read bedtime stories

I thought that ‘executive summary’ nursery rhymes, for time-pressed parents to read to their children, were bad enough. I think this might be worse. Not only are we removing human interaction, we are allowing Big Tech to listen in on our children.