Given it’s A-Level results day today, and GCSE results next week in the UK, I thought this might be worth re-posting…

What is the purpose of a university? What

should they seek to encourage? You might think that universities, of all

places, might be thinking more about this, but alas no. This exam question has

largely fallen off the curricula. Neither is much study time being given to

whom an Australian university should serve, how they might be funded or what should

be taught and why.

There was a time when a university was a

place where people were taught to think. They were communities of open debate.

They were places where people went to be educated into the way of the world

using grammar, rhetoric and logic. They were spaces where people went to

explore and understand things, not least themselves. There were no ‘safe

spaces’ or no-platform policies.

Universities nowadays are becoming where you

go to further your career and earn more money. Following the Dawkins reforms in

the late 1980s, students are now customers with all the biases and baggage this

word entails. With notable exceptions, universities have become brands that

churn out qualifications much in the same way that fast food establishments

flip burgers, although it’s sometimes difficult to tell which might be more

damaging over the longer term.

Time to upgrade the system

A thriving university sector is essential in

a hyper-competitive world where problems are becoming trickier and constraints

are becoming stickier. But Australia is still stuck on a system created more

than a century ago to produce muscle or memory workers for business. These are

people taught physical dexterity, precision and endurance or taught to process

and apply information according to sets of rules.

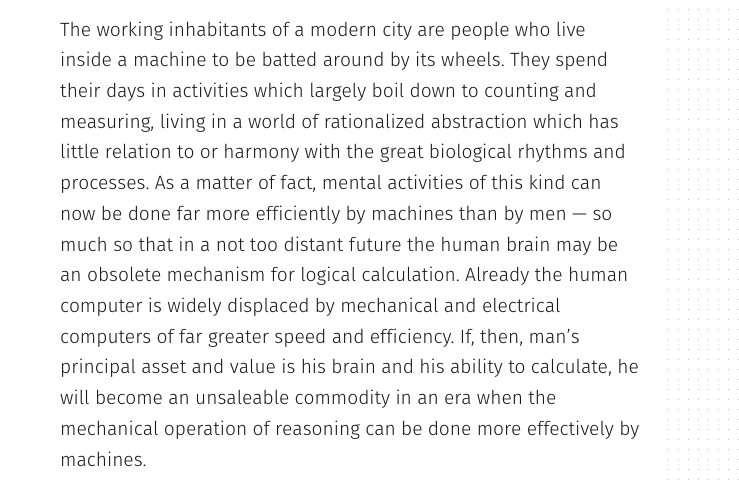

This output has suited us up to now, but

looking ahead it seems that developments in machine learning and artificial

intelligence mean that we are teaching a generation to compete head on with

computers and it’s a no-brainer who will win if the contest is about muscle,

precision, memory, data processing or logic.

With the exception of teaching people

how to create or collaborate with these machines, we should be teaching

precisely the opposite, which is how to think in ways that computers can’t.

Ultimately, there’s not a lot that machines

can’t do if we allow them, but there could be a few domains that will remain

the preserve of primitive carbon-based bipeds such as ourselves. The first is

creativity. We should be teaching students how to think more imaginatively,

whether the application be art, science or the art and science of innovation.

We need tall buildings that don’t fall down, but also ones that make the human

heart soar.

Similarly, logical machines, no matter how

smart, will continue to struggle with the faults and foibles of human beings,

which, to my mind, means it matters that we teach people about other people and

what motivates them.

Machines can be alluring, but I can’t see

them ever being inspiring, so teaching leadership should be paramount, whatever

the discipline you are attempting to impart. One of the issues I hear about

regularly is that of students entering the workforce that are technically

brilliant, but incapable of managing themselves let alone anyone else. Recognising

and rewarding EQ alongside IQ might be a good way to not only create a

functioning civil society and workforce, but also a way of creating the next

generation of effective leaders.

But don’t suppose for a moment that this can

be achieved online. We already have a problem with asocial students virtually

incapable of human interaction. Let’s not make this worse by deleting the human

interface.

A further thing that’s missing from the

current system is ethics. Historically, many universities were linked to the

church and the moral component was bedrock. Nowadays, the moral component of a

degree is akin to a slippery slope of scree sliding down a hillside. Indeed,

it’s quite possible to use your head to pass through university with flying

colours while remaining, at heart, an ego-centric, narcissistic, psychopath.

One thing I stumbled upon recently was the

4Cs (Critical thinking, Communication, Collaboration, Creativity). I propose

that we build upon this list and set off toward the distant horizon of 2040 on

the 7Cs: Critical thinking, Creativity, Collaboration, Communication,

Curiosity, Character and Compassion.

The first 4Cs are self-explanatory.

We need people to think Critically and

Creatively about the world’s problems and Communicate and Collaborate across

communities to come up with solutions. But the last 3Cs are especially

important.

The aim of education generally, and of

universities in particular, should be to instil a lifelong love of learning and

this is becoming especially vital in a world where new knowledge is being

created at an exponential rate.

But how can we expect people to continually

re-learn things without first instilling a sense of Curiosity about how things

work or might be changed for the better? Character is important for two

reasons. First, as machines become more adept at doing the things that were

once thought the preserve of humans, the value of emotionally based work should

come to the fore. Most jobs feature people at some level and if you are trying

to persuade people to do something you’re more likely to be successful if you

are liked. An attractive personality cannot be taught, but it can be

encouraged. Moral Character is equally important. We don’t just want smart

graduates, we want ethically grounded graduates too.

The final C, Compassion, is linked to moral

character. Compassion is the resource the world is running out of faster than

any other. Without Compassion the world is an ugly place.

Universities have long focussed on IQ.

Indeed, it’s hard to get into a university without it. But at the risk of

repeating myself, EQ might prove more valuable over the longer term, especially

if IQ becomes the preserve of artificially intelligent machines.

It’s hard to predict the future, and foolish

to try in many instances, but I believe that imparting individuals with a

better understanding of the human operating system would make them better

prepared for whatever 2040 throws at them.

Original article here.