A university in the United Kingdom recently asked its students to write essays on whether the future was open or closed — an open future being one where anything could happen, a closed future being where a single or fixed future had become inevitable. Without exception the students all wrote essays about closed futures.

But if there is one thing we can be certain of concerning the future, it is surely that it will always be uncertain. There must always be many ways in which the future could unfold or be amended.

We have been engaged as futurists for more than 30 years with the needs of businesses, governments, and non-profit organisations to grasp the nettle when it comes to the question of “What’s next?” and to investigate how future-proof is our organization to the cluster of change agents circling our operating environment.

Over this time, we have come to think of the future as a terra incognita, a landscape that some people may claim to have seen, but one where the terrain remains mostly unknown beyond some basic geographical and geological elements. The millions of people that will, as Oxford’s William MacAskill outlines in his breathtaking book What We Owe the Future, inhabit this cloud-covered land are also largely unknown, so we have an ethical responsibility to rehearse how we should behave towards them to optimize the outcomes both for them and ourselves.

But the more we have grappled with the uncertainties of the future it has become increasingly clear that the future only exists in the present. Adapting Benedetto Croce’s aphorism about history, all futures are contemporary futures. They are not, after all, imagined destinations but rather complex world views through which we look at today. They are reflections of who we are, where we have been and where it is that we would like to travel next.

All futures are contemporary futures. They are not, after all, imagined destinations but rather complex world views through which we look at today. They are reflections of who we are, where we have been and where it is that we would like to travel next.

T. S. Eliot, like many artists (for example, where would modernist architecture be without Mondrian?), got there before us. In Burnt Norton, the first of his Four Quartets, he said:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

What might have been is an abstraction

Remaining a perpetual possibility

Only in a world of speculation.

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

….

human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

Cataloguing these world views is not hard provided we own up to what we are really doing. It is notable that we futurists are rarely employed to predict or forecast the future. Rather we are hired to either validate a journey that is already well underway or to fashion alternative futures or scenarios that flow logically from the contemporary present.

An Australian client interested in the future of primary industries, selected one future scenario from the four worlds we had created as a preferred future and set about using this “prediction” as the purpose of the scenario planning exercise. In other words, the future was an excuse to justify a pre-existing view of the future or perhaps to reassure everyone that everything would turn out alright.

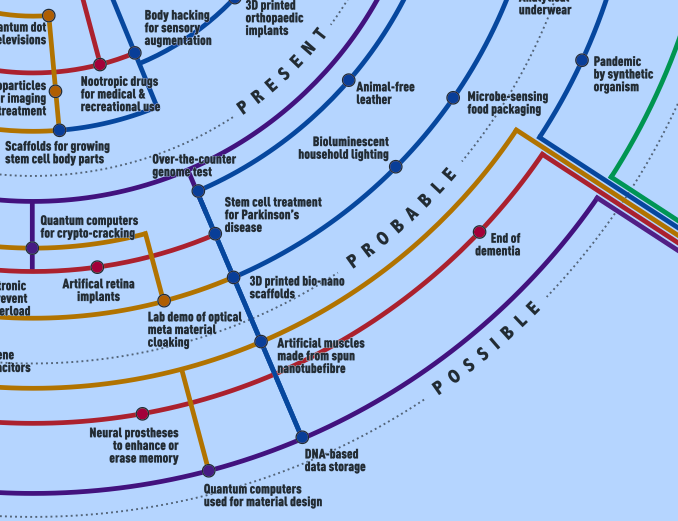

In scenario work the most important building blocks are what we call the critical uncertainties shaping the external environment in which scenario-client organisations operate. Over the last 30 years, across 30 or so projects, the favored drivers of change we have encountered have been in areas such as China & Geopolitics, Climate Change & Environmental Sustainability, Artificial Intelligence & Technology, Generational & Social Change, Economics & Happiness – not forgetting Culture Arts, & Entertainment

Foresight is, inevitably, an indulgence. If you are on a sinking ship, which perhaps the university students thought they were, the exercise can be little more than distraction. The proverbial deckchairs onboard the Titanic.

But foresight remains an activity which encourages us to think in abstract ways – literally by conjuring up artefacts that have no independent existence from our emotions and intelligence. This is most evident in the field of macro-economics which has become the melting pot in which the forces driving the environment in which we live collide with each other. They create abstractions that we then use to validate public policies that seek to optimise outcomes for nations and the world.

Think of inflation, unemployment, GDP, aggregate demand/supply, and economic growth as just some of the key variables that governments slavishly rely upon to determine their fiscal and monetary policies. What do all these items have in common? Simply, it is that they do not exist. You can’t touch them or feel them.

Rather, they are abstractions reliant on the algorithmic values that are used to generate what data is collected and why – reliant on the underlying world views of those collecting the data.

For example, when you attempt to disentangle the mishmash of driving forces that create inflation, it becomes impossible to generate logical descriptions of future environments. There is simply too much going on for the future to settle. This is perhaps the contemporary problem with futures and thus its future.

Perhaps Douglas Rushkoff was right, with all futures collapsing into a chaotic present.

After all, how can you engage people into thinking about unfamiliar futures when the recent past contains a reality TV star becoming the U.S. president, the UK waving goodbye to its European cousins, a virus inflicting infection upon the world, and a tank war in Europe that oscillates between the trenches of 1914 and the futuristic fantasies of H G Wells. Everything happens, everywhere, all at once. Unfathomable parallel universes simultaneously collapsing into a black hole from which the light of “it might be alright” cannot escape.

No wonder Major Tom became a junkie (David Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes) and no surprise that William Gibson, anticipating AI in his seminal cyber-punk novel Neuromancer, eventually gave up writing novels set in the future. The present is quite strange enough thank you very much. There is no bandwidth left to think beyond the present. Even the so-called news has become too much to bear. If it bleeds it leads, but if it calms our fears it disappears. Too much reality? Escape into a virtual insanity. At least you won’t be alone.

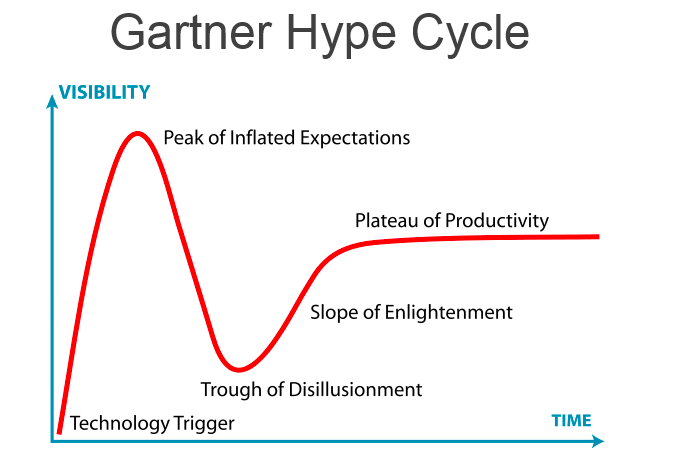

Our current engagement with AI similarly tells us a lot about the impossibility of the future. AI is more than a critical uncertainty with a range of potential futures. It is a basket of unknown unknowns whose systemic consequences are Black Swans beyond our comprehension.

Even death and taxes come to grief in an AI future funded by Tech Titans using the spoils of privacy invasion and algorithmic recommendation to fund massive rockets (Freud anyone?) and/or longevity research (Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray perhaps?)

It is unsurprising then that we live in a world without a future. As a result, cultural attention and financial investment is moving to a compressed and accelerated present. Two cultural phenomena support this point of view. The first is the rise of populism fuelled by social media, the second is AI.

We are living in a world where news – fake or otherwise – travels quickly and conversations based on providers like Tik Tok, Instagram and Twitter are interested only in the here and now, so much so that in many channels the uploaded content has a very short life before it disappears. The cycle of news is quickening and shortening every day. Here today and gone today.

The second phenomenon is more one of social psychology. Mindfulness is the case in point. It teaches that preoccupation with what might become a deterministic tomorrow needs to be abandoned in place of a total non-judgmental preoccupation with the present.

As T.S. Eliot prompted the concepts of present and future worlds that are muddling and confused as well as steeped in uncertainty as to their origin.

He also cast doubt on the idea of the past, and would have endorsed Russian economist and politician Yavlinsky’s comments in a futures workshop in Provence some years back when he declared that for Russia the greatest level of uncertainty belonged to the past. How can we agree on our future if we can’t agree on our past”? And anyway, the future is too far away to matter.

Maybe the students with closed minds are right after all?

No future indeed.

Richard Watson and Oliver Freeman. Extracted from Compass magazine, December 2023.