While I’m on the subject of digital detox (previous post), a few of you might have school age kids on holiday at the moment. Chances are you are frantic trying to organise things for the little darlings to do. Don’t. Read this instead.

Boredom is beautiful. Rumination is the prelude to creation. Not only is doing nothing one of life’s few remaining luxuries, it is also a state of mind that allows us to let go of the external world and explore what’s deep inside our head. But you can’t do this if ten people keep sending you messages about what they are eating for lunch or commenting on the cut of your new suit. Reflection creates clarity. It is a “prelude to engagement of the imagination,” according to Dr. Edward Hallowell, author of Crazy Busy. It is a useful human emotion and one that has historically driven deep insight.

Boredom hurts at first, but once you get through the mental anguish you can see things in their proper context or sometimes in a new light. Digital technology, and mobile technology in particular, appears to negate this. If you are trying to solve a problem it is now far too easy to become digitally distracted and move on. But if you persist, you might just find what you’ve been looking for. So don’t just do something after you’ve read this chapter, sit and think for a while.

Faced with nothing, you invent new ways of doing something. This is how most artists think when faced with a blank canvas. Historically, children have operated like this too. They moan and groan that they are bored, but eventually they find something to do—by themselves. Boredom is a catalyst for creative thought. Only these days it mostly isn’t. We don’t allow our children the time or the space to drift and dream. According to the UK Office of National Statistics, 45 percent of children under 16 spend just 2 percent of their time alone. Moreover, the amount of free time available to schoolchildren (after going to school, doing home- work, sleeping, and eating) has declined from 45 to 25 percent. Children are scheduled, organised, and outsourced to the point where they never have what New York University Professor Jerome Wakefield calls a chance to “know themselves.” It’s the same with adults. Our minds are rarely scrubbed and dust builds up to the point where we can’t see things properly.

Not only is it difficult to become bored, we can’t even keep still long enough to do one thing properly. Multitasking is killing deep thinking. Leo Chalupa, an ophthalmologist and neurobiologist at the University of California (Davis), claims that the demands of multitasking and the barrage of aural and visual information (and disinformation) are producing long-lasting and potentially permanent damage to our brains. A related idea is constant partial attention (CPA). Linda Stone, who has worked at both Apple and Microsoft Research Labs, knows about how high-tech devices influence human behaviour. She coined the term CPA to describe how individuals continually scan the digital environment for opportunities and threats. Keeping up with the latest information becomes addictive and people get bored in its absence.

In a sense this isn’t anything new. We were all doing this 40,000 years ago on the savannah, tucking into freshly killed meat while keeping keeping a look out for predators. But digitisation plus connectivity has increased the amount of information it’s now possible to consume to the extent that out attention is now fragmented all of the time. This isn’t always a bad thing, as Stone points out. It’s merely a strategy to deal with certain kinds of activity or information.

However, our attention is finite and we can’t be in hyper-alert, “fight-or-flight” mode 24/7. Constant alertness is stressful to body and mind and it is important to switch off, or at least reduce, some of the incoming information from time to time. As Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slow, says: “Instead of think- ing deeply, or letting an idea simmer in the back of the mind, our instinct is now to reach for the nearest sound bite.” We relax by cramming even more information into our heads.

Chalupa’s radical idea is that every year people should be encouraged to spend a whole day doing absolutely nothing. No human contact whatsoever. No conversation, no telephone calls, no email, no instant messaging, no books, no newspapers, no magazines, no television, no radio, and no music. No contact with people or the products of other human minds, be it written, spoken, or recorded.

Have you ever done nothing for 24 hours? Try it. It will do your head in for a while. Total solitude, silence, or lack of mental distraction destroys your sense of self. Time becomes meaning- less and recent memories start to disappear. There is a feeling of being removed from everything while being deeply connected to everything in the universe. It is fantastic and frightening all at the same time. But don’t worry, you soon feel normal again. Return to sensory overload and deep questions about a unifying principle for the universe soon disappear, to be replaced by important questions about what you’re going to eat for dinner tonight or how you’re going to find that missing Word file.

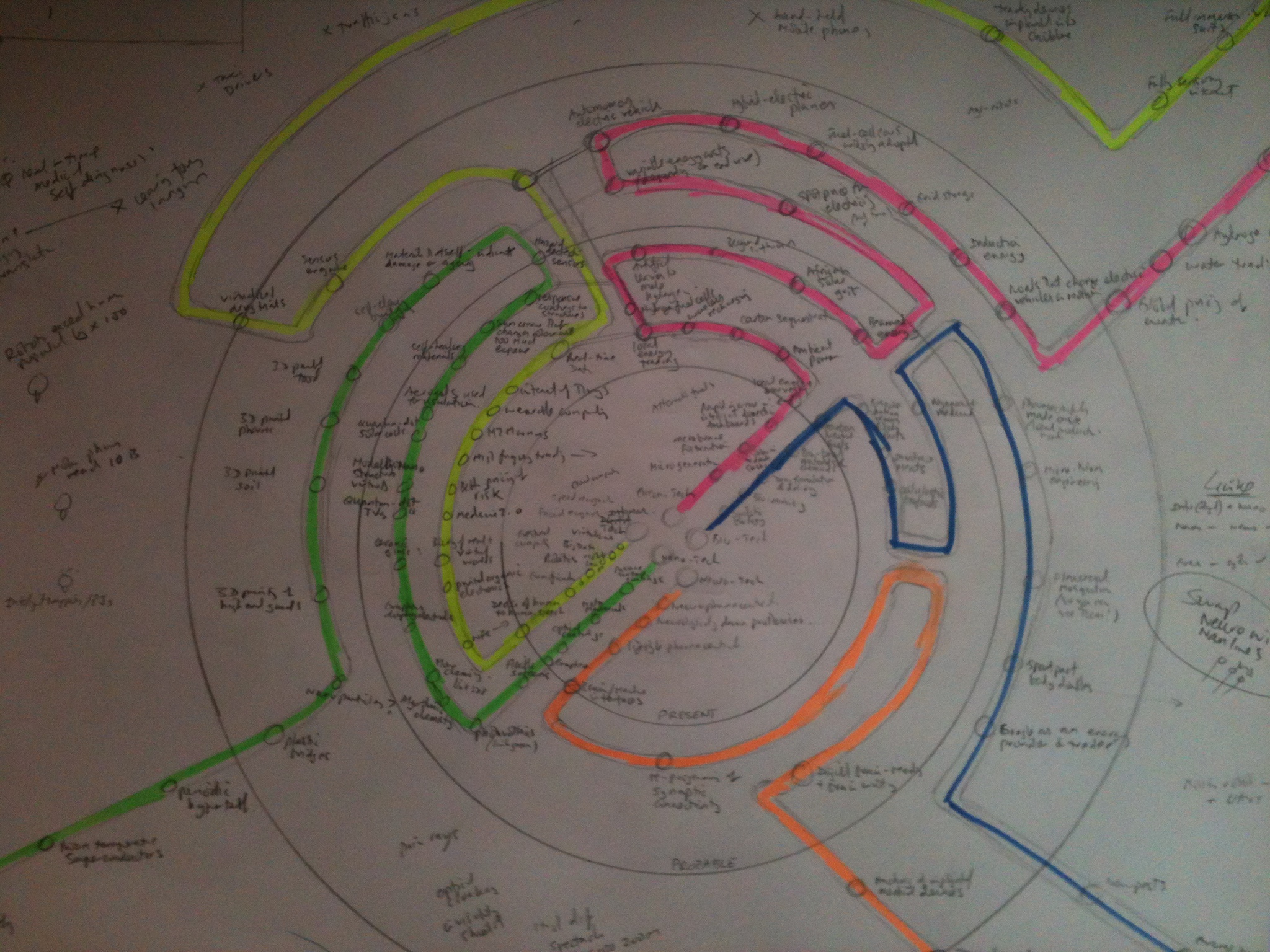

Consider what Bill Gates used to do. Twice a year for 15 years the world’s then richest man would take himself off to a secret waterfront hideaway for a seven-day stretch of seclusion. The ritual and the agenda of Bill’s think weeks were always the same: to ponder the future and to come up with a few ideas to shake up Microsoft. In his case this involved reading matter but no people. Given that Gates has been instrumental in the design of modern office life, it’s interesting that he felt the need to get away physically; one would expect him to inhabit a virtual world instead.

I once received a brief from the strategy director of a FTSE 100 company who wanted to take his team away to do some thinking. When I suggested that we should do just that—go away for a few days, read some books, think, and then discuss what we’d read— he thought I’d lost my mind. Why? Because there was “no process.” There were no milestones, stage gates, or concrete deliverables against which he could measure his investment.

The point of the exercise is this. Solitude (like boredom) stimulates the mind in ways that you cannot imagine unless you’ve experienced it. Solitude reveals the real you, which is perhaps why so many people are so afraid of it. Empty spaces terrify people, especially those with nothing between their ears.

But being alone and having nothing to think about allows your mind to refresh itself. Why not discover the benefits of boredom for yourself?