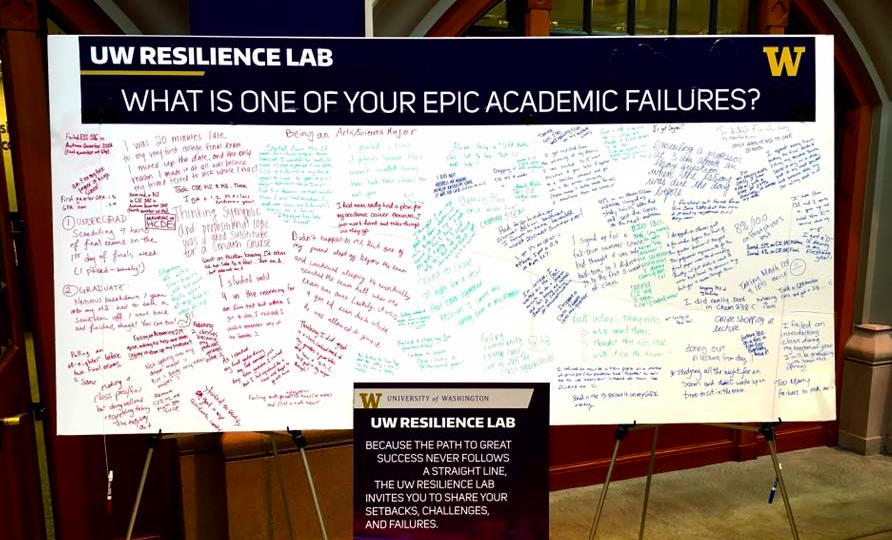

I rather like the school that has withdrawn Christmas on the basis that students need to make a case for why it needs to be reinstated. However, my idea of the year award for 2018 goes to the genius who came up with the idea of Failure CVs (having been in the midst of personal statement season of late this makes a refreshing and more honest alternative).

Johannes_Haushofer_CV_of_Failures

Something I wrote about failure a very long time ago..

You don’t read about failure very often. And I’m not just talking about ideas that don’t see the light of day. I’m talking about people too. Why is this? What are we afraid of? After all, it’s not as if it’s unknown. Most companies — indeed, most people — fail more often than they succeed. It is the proverbial elephant-in-the-boardroom. And yet by being scared of failure, we are missing a great opportunity.

The point about failure is not that it happens but what we do when it happens. Most people flee. Or they find a way to be “economical with the actualite” as a former British Government so elegantly described it.

“We launched too late.” “Consumers weren’t ready for it.”

No. You failed. Own up to it. Own it. This is a beginning, not the end.

The problem is this: Most people believe that success breeds success and they believe that the converse is true too, that failure breeds failure. Says who? There are plenty of people who fail before they succeed, some of whom are serial failures. Indeed, there is rumoured to be a venture capital firm in California that will only invest in you if you’ve gone bankrupt twice.

Take James Dyson, the inventor of the bag-less vacuum cleaner. He built 5,127 prototypes before he found a design that worked. He looked at his failures and learned. He then looked at his next failure and learned some more. Each adaptation led him closer to his goal. As someone once said, there’s magic in the wake of a fiasco. It gives you the opportunity to second guess.

None of this is to be confused with the mantra of most motivational speakers who urge you not to give up. Success is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration they say, and if you just keep on trying, it will eventually happen. And if it doesn’t, you’re just not trying hard enough. This is a big fat lie. Doing the same thing over and over again in the hope that something will change is almost the definition of madness. What you need to do is learn from your failure and try again differently.

All of which brings me to my first point. It is what you do when you fail that counts. Remember Apple’s message pad, the Newton? This was a commercial flop, but the failure was glorious. Indeed, who is to say that the tolerance of failure that is embedded in Apple’s DNA is not one of the reasons for Apple’s success with the iPod and iTunes?

Does this mean you abandon your failures? Yes and no. Your idea could be right but your timing, delivery, or execution could be wrong. Who could have guessed that the one-time AIDS wonder drug AZT had been a failed treatment for cancer or that Viagra was a failed heart medication that Pfzer stopped studying in 1992?

As Alberto Alessi once said, anything very new often falls into the realm of the not possible, but you should still sail as close to the edge as you can, because it is only through failure that you will know where the edge really is. The edge is also where real genius resides.

So what I’m interested in promoting are the people whose ideas never get off the ground or rather get somewhere other than where they intended. These are the people who fail on our behalf. The unknown innovators that push things so far to the edge that they fall off. The unlucky or naïve few who open up a new trail — and get scalped — before someone else can see a way through with the wagons. (How’s that for a new historical definition of second-mover advantage?)

There’s a great quote by the English sculptor Henry Moore that sums this up pretty well: “The secret of life is to have a task, something you bring everything to, every minute of the day for your whole life. And the most important thing is: It must be something you cannot possibly do.”

So here’s my idea. Rather than putting up statues to people who did something that was successful, let’s build a monument to the people who didn’t. Let’s celebrate the lives of people who invented things that didn’t work or tried to do something that was just plain crazy. A monument to the unknown innovator in pursuit of an impossible dream. The people we watch with perverse envy when we are too scared, too self-conscious, or too constrained to fail ourselves. Because without these wonderful people, there would be no progress or success.

Here are my top five tips for failing with greater frequency and style:

- Try to fail as often as possible but never make the same mistake twice.

- Set a failure target as part of each employee’s annual review.

- If projects are a failure, kill them quickly and move on.

- Create a failure database as part of knowledge management.

- Set up annual failure awards. If this gets too successful, stop it. (Stephen Pile’s Book of Heroic Failures spawned the Not Terribly Good Club of Great Britain. Unfortunately the club received 30,000 membership applications and had to be closed down because it was a failure at being a failure.)