I’ve thought about putting this thought into the ether before, but I’m all too aware of confirmation bias and the fact that what I’m about to say might be the future I want rather than the future that is unfolding. I’m also far too aware of the words of the writer Douglas Adams, who said that: “anything that gets invented after you’re thirty is against the natural order of things and the beginning of the end of civilisation as we know it until it’s been around for about ten years when it gradually turns out to be alright really.”

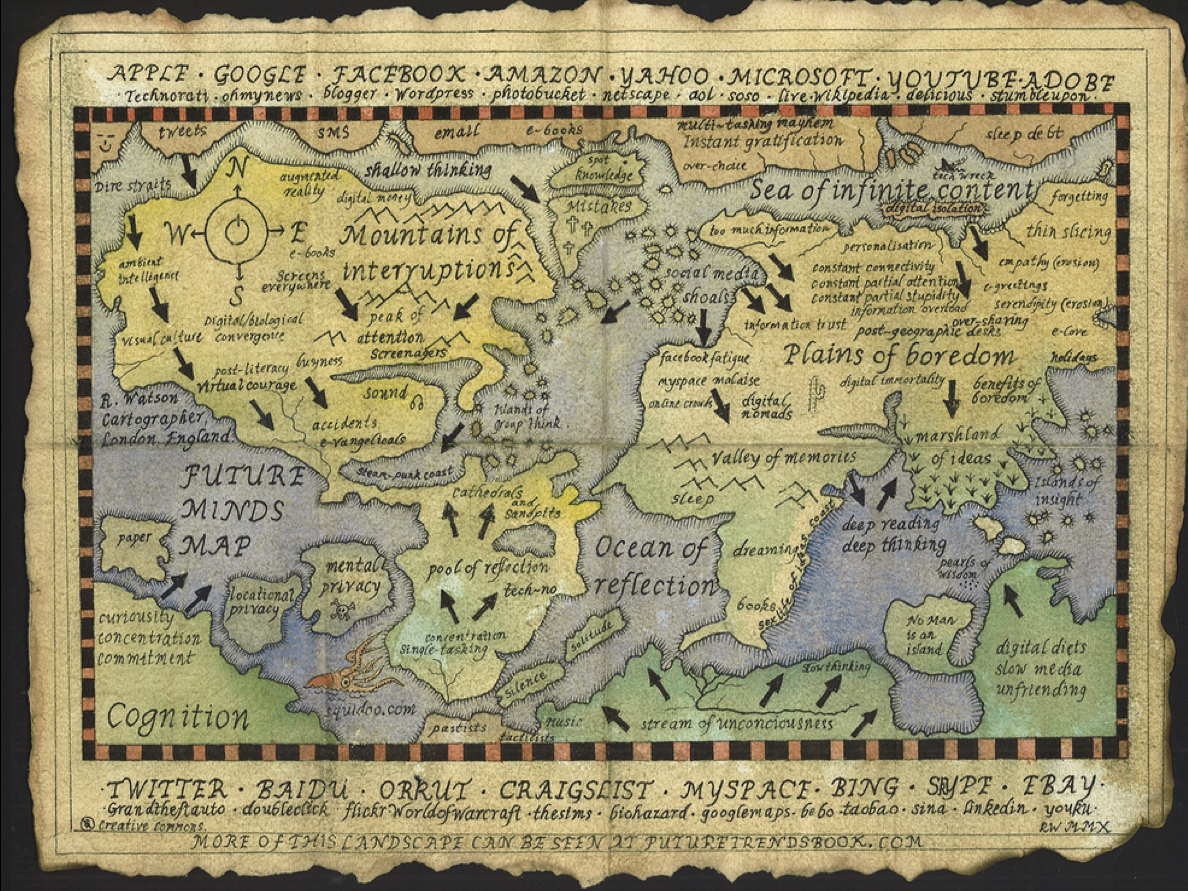

So, I’m being cautious. Nevertheless, I’m becoming aware of a rising tide of discontent regarding Big Tech, social media and smartphone use. A number of people I’ve met recently are also starting to articulate a future with no internet in it or at the very least a future where we have a significantly altered and re-balanced relationship with the internet and our devices.

Exhibit 1. A London lawyer in his twenties that I met last week could foresee a time when people become so disillusioned with the internet, smart phones and social media that they drift away from it. Key issues for him were data security, individual privacy and a lack of censorship with regard to unacceptable material (e.g. easy access of pornography by young kids with smartphones at school).

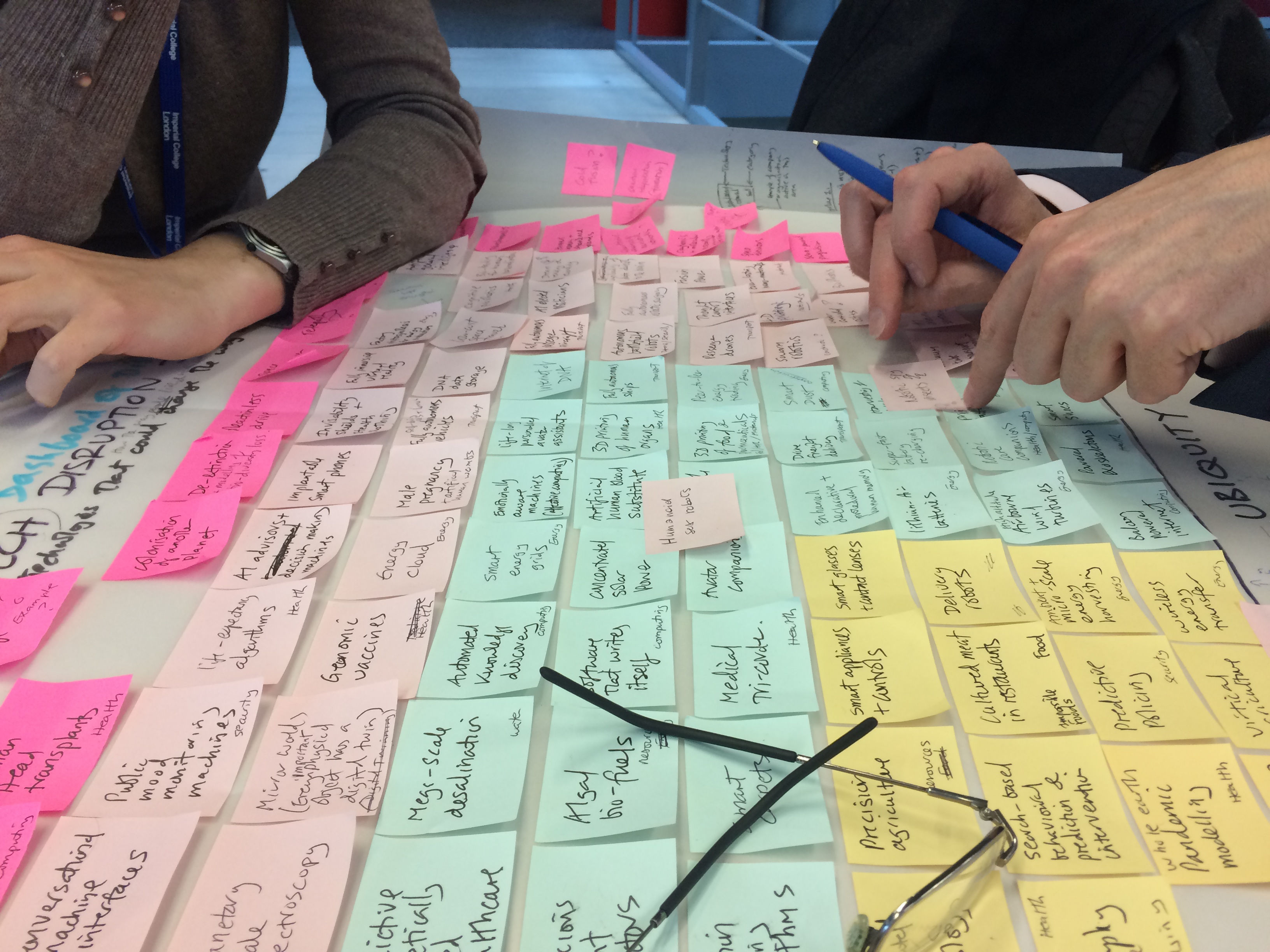

Exhibit 2. I forecast a Big Tech Backlash two years ago and it appears on my map of megatrends published back in May. I was in Silicon Valley a few weeks ago and while I’m used to reading articles about Facebook being the anti-Christ there was a fairly hostile opinion piece about Google in the US edition of Wired magazine of all places. There was also an article about throwing technology out of younger years education in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Exhibit 3: I’m starting to see words like ‘addition’ being used on an almost daily basis in relation to digital technology.

Exhibit 4: The attitudes and behaviour of Uber recently/generally.

Exhibit 5: The fact that owning the latest smart phone isn’t cool in parts of Silicon Valley. (see also the popularity of ‘dumb phones’).

Exhibit: 6: UK schools starting to end their ‘do as you want/anything goes’ policy regarding the use of technology on school premises. One school I know personally has gone as far as banning pupils from using mobiles during the day. iPad hysteria in educational circles also seems to have died down.

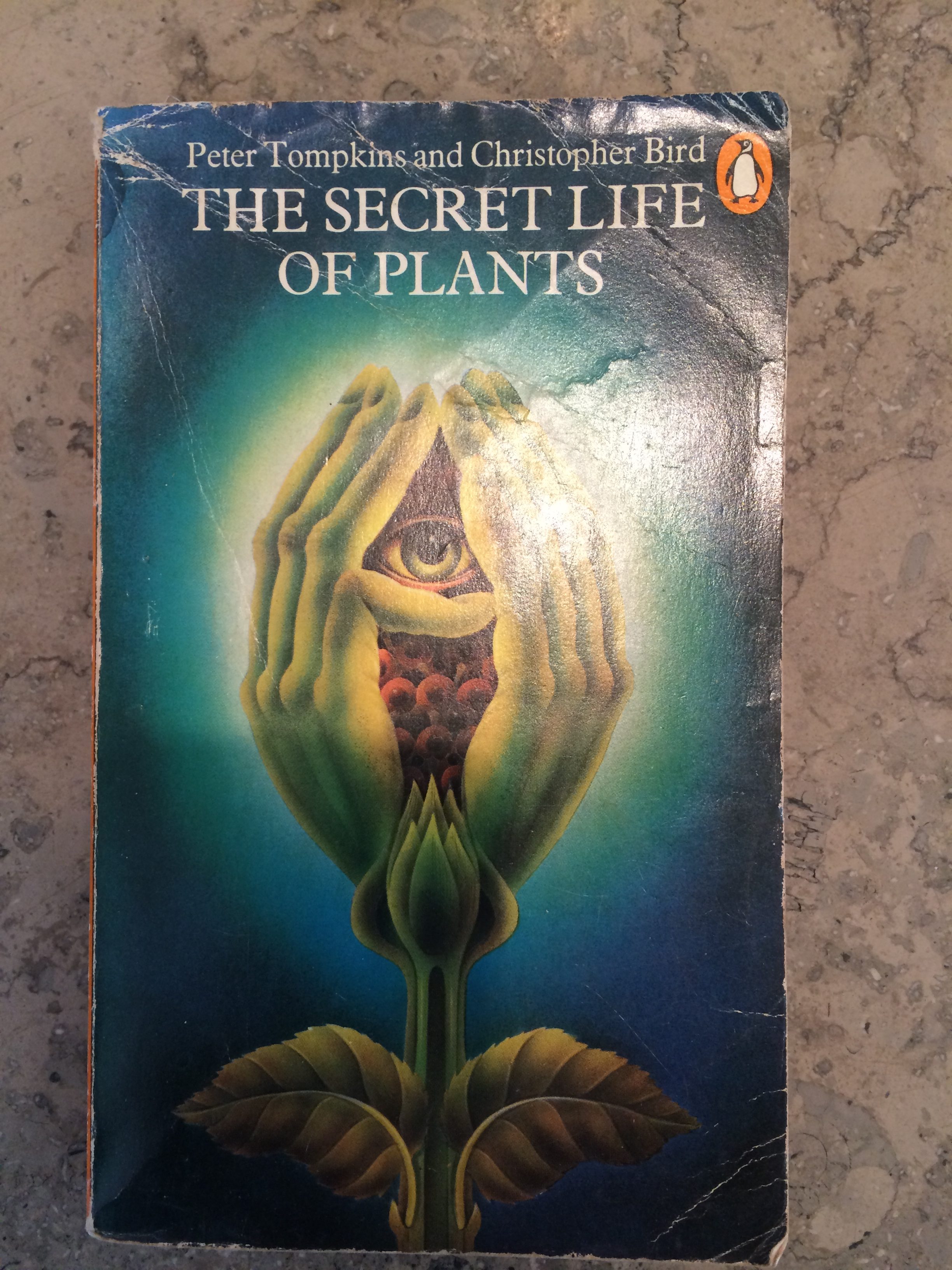

Exhibit 7: Remember e-cards? Exactly. They were the future a decade ago, but it eventually dawned on us that digital can be sterile and characterless while analogue can be sensory. People are sending me handwritten cards again. Also witness the re-birth of vinyl records, paper books and fountains pens. Sending someone an e-card for Xmas might be convenient or cheap, but it can signify that you too are cheap and can’t be bothered to invest time or effort in a relationship. Can deep human needs and desires trump convenience or price?

It should be noted here (because it rarely is) that digital and physical are different on many levels. It’s not so much embracing the one and rejecting the other (a rather binary outlook) but rather working out which is better in a particular context or circumstance.

Exhibit 8: If digital tech is so great why do so many senior people working for companies like Apple and Google send their kids to schools like the Waldorf School of the Peninsula, where there’s virtually no computer to be found? Schools such as this one are increasingly arguing that computers and learning don’t mix well, diminishing attention, inhibiting creativity, and weakening human relationships. This might please Eric Schmidt at Google, who once said, ‘I still believe that sitting down and reading a book is the best way to really learn something.’ (See exhibit 6).

Exhibit 9: The behaviour of teens. Filters on Instagram are becoming passe. Facebook is dead in the water in developed markets and back in schools smart kids are revising using paper cards because, as one explained to me: “you remember things better.”

Exhibit 10: Not an exhibit, but an idea. There are surely events that could radically reshape the digital landscape. What if Google or Facebook were redefined as publishers rather than technology platforms, for example? What if they were regulated in exacatly the same way as a newspaper or TV station? What if they were viewed as monopolies and broken up? Or what if Google simply decided to charge a cent for every search? The biggest vulnerability beyond all this, it seems to me, is simply that the ad model breaks down. Take advertising away and a significant chunk of the internet simply ceases to exist.

These are minor and largely anecdotal examples, but worth watching all the same.

BTW, one thing that isn’t being commonly discussed, surprisingly, is the idea that the data that many tech companies create value from is our data, stolen from us largely without our explicit consent. (oh please, you think people really read those terms and conditions?)