Something I’ve written about Deep Fakes for the Metro newspaper

Author Archives: Richard

Searching for God on Google

Well, OK, it’s on Amazon, but Google planning to connect people with God too.

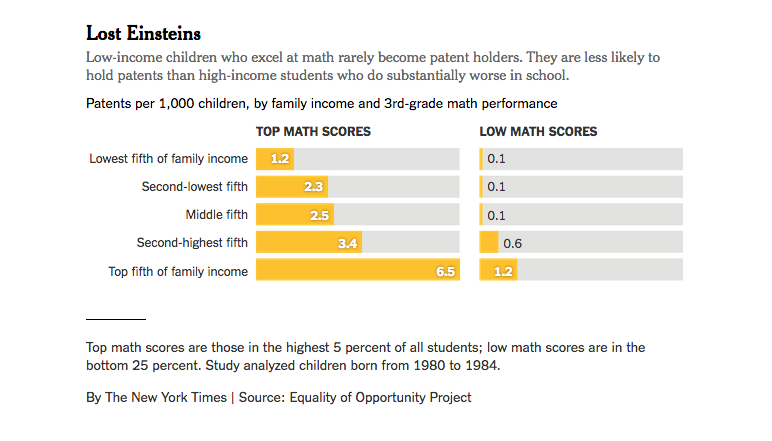

Lost Einsteins

Funny how two words can be so powerful. An article in the New York Times about a Stanford study looking at what influences potential Einsteins. This graph below concerns income, other graphs look at race and gender. Thanks for Chris at Nesta who mentioned this to me.

Robots Vs. People

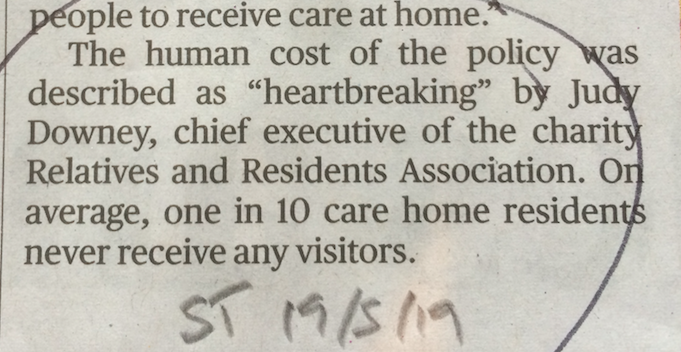

I attended a conference on AI at Cambridge University last week and one of the most interesting points was why we were developing robots to look after old people – why not just use people? The answer could be that we are running out of people, especially younger people, as is the case in Japan, but this simply begs another question. Why don’t we either educate younger people on the importance of looking after older people, especially one’s own relatives, or simply conscript younger people into the NHS for short periods (a wonderfully provocative idea proposed by Prof. Ian Maconochie at an Imperial College London lecture the other week).

I attended a conference on AI at Cambridge University last week and one of the most interesting points was why we were developing robots to look after old people – why not just use people? The answer could be that we are running out of people, especially younger people, as is the case in Japan, but this simply begs another question. Why don’t we either educate younger people on the importance of looking after older people, especially one’s own relatives, or simply conscript younger people into the NHS for short periods (a wonderfully provocative idea proposed by Prof. Ian Maconochie at an Imperial College London lecture the other week).

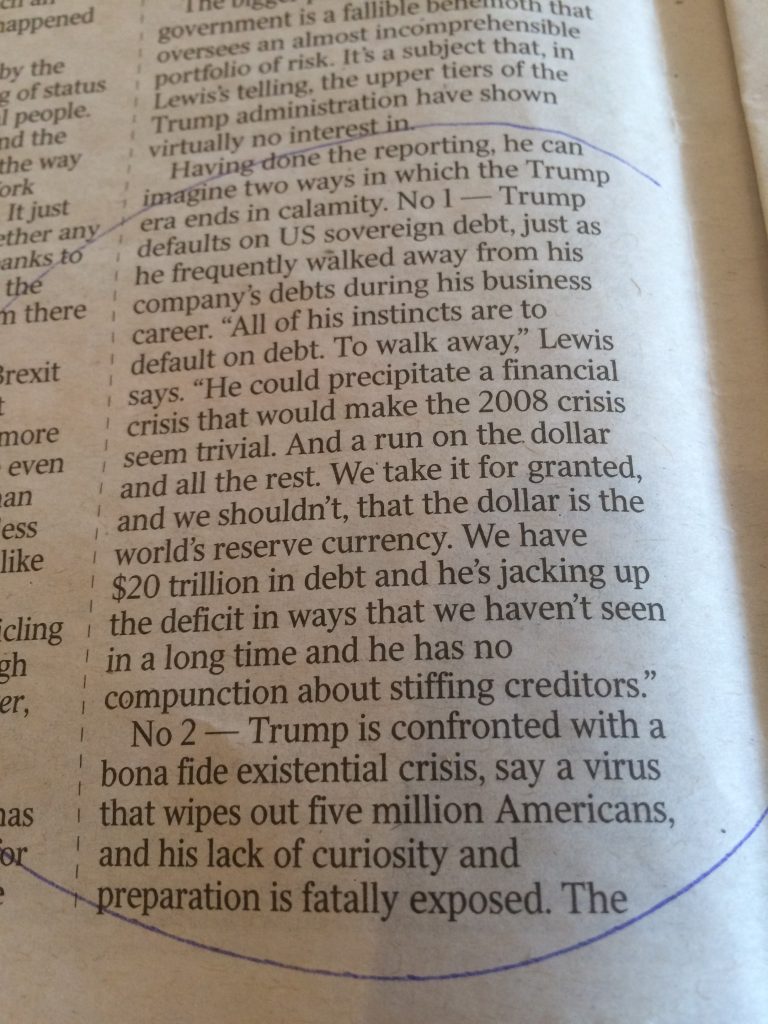

OK, how about this one? (same publication)

Is this just a little bit let Continue reading

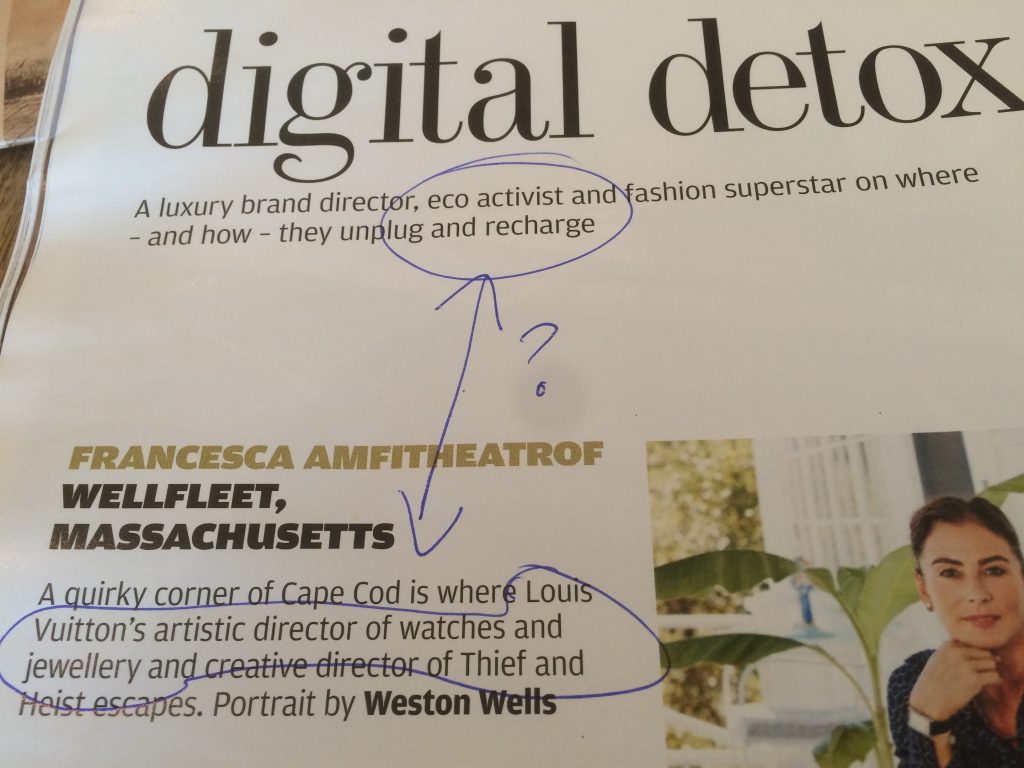

Slight contradiction?

Louis Vuitton is a luxury brand. The word luxury comes from the latin luxus, meaning excess and the latin luxuria, meaning rank or offensive. You cannot work for a luxury brand and be an eco-activist.

New Map

Peak Blog Post

After 15 years I think I may have reached peak posting. I’m running out of puff. If I regain some puff I’ll let you know, but in the meantime here’s another circled sentence from a random publication.

What can’t computers do?

Are you worried that your job could be ravaged by a robot or consumed by a computer? You probably should be judging by a study by Oxford University, which said that up to half of jobs in some countries could disappear by the year 2030.

Similarly, a PEW Research Centre study found that two-thirds of Americans believe that in 50 years’ time, robots and computers will “probably” or “definitely” be performing most of the work currently done by humans. However, 80 per cent also believe that their own profession will “definitely” or “probably” be safe. I will come back to the Oxford study and the inconsistency of the two PEW statements later, but in the meantime how might we ensure that our jobs, and those of our children, are safe in the future?

Are there any particular skills or behaviours that will ensure that people are employed until they decide they no longer want to be? Indeed, is there anything we currently do that artificial intelligence will never be able to do no matter how clever we get at designing AI?

To answer these questions, we should perhaps first consider what it is that AI, automated systems, robots and computers do today and then speculate in an informed manner about what they might be capable of in the future.

A robot is often defined as an artificial or automated agent that’s programmed to complete a series of rule-based tasks. Originally robots were used for dangerous or unskilled jobs, but they are increasingly being used to replace people when people are too inefficient or too valuable. Not surprisingly, machines such as these are tailor made for repetitive tasks such as manufacturing or for beating humans at rule-based games. A logical AI can be taught to drive cars, another rule-based activity, although self-driving cars do run into one rather messy problem, which is people, who can be emotional, irrational or ignore rules.

The key word here is logic. Robots, computers and automated systems have to be programmed by humans with certain endpoints or outcomes in mind. If X then Y and so on. At least that’s been true historically. But machine learning now means that machines can be left to invent their own rules and logic based on patterns they recognise in large sets of data. In other words, machines can learn from experience much as humans do.

Having said this, at the moment it’s tricky for a robot or any other type of computer to make me a good cup of coffee, let alone bring it upstairs and persuade me to get out of bed and drink it. That’s the good news. A small child has more general intelligence and dexterity than even the most sophisticated AI and no robot is about to eat your job anytime soon, especially if it’s a skilled or professional job that involves fluid problem solving, lateral thinking, common sense, and most of all Emotional Intelligence or EQ.

Moreover, we are moving into a world where creating products or services is not enough. Companies must now tell stories and produce good human experiences and this is hard for machines because it involves appealing to human hearts as well as human heads.

The future will be about motivating people using stories not just numbers. Companies will need to be warm, tolerant, personable, persuasive and above all ethical and this involves EQ alongside IQ. Equally, the world of work is less about command and control pyramidal hierarchies where bosses sit at the top and shout commands at people. Leadership is becoming more about informal networks in which inspiration, motivation, collaboration and alliance building come together for mutual benefit. People work best when they work with people they like and it’s hard to see how AIs can help when so much depends on passion, personality and pervasiveness.

I’m not for a moment saying that AI won’t have a big impact, but in many cases I think it’s more a case of AI plus human not AI minus human. AI is a tool and we will use AI as we’ve always used tools – to enhance and extend human capabilities.

You can program machines to diagnose illness or conduct surgery. You can get robots to teach kids maths. You can even create algorithms to review case law or predict crime. But it’s far more difficult for machines to persuade people that certain decisions need to be taken or that certain courses of action should be followed.

Being rule-based, pattern-based or at least logic-based, machines can copy but they aren’t generally capable of original thought, especially thoughts that speak to what it means to be human. We’ve already seen a computer that’s studied Rembrandt and created a ‘new’ Rembrandt painting that could fool an expert. But that’s not the same as studying art history and subsequently inventing abstract expressionism. This requires rule breaking.I’m not saying that AI created creativity that means something or strikes a chord can’t happen, simply that AI is pretty much stuck because of a focus on the human head, not the human heart. Furthermore, without consciousness I cannot see how anything truly beautiful or remotely threatening can ever evolve from code that’s ignorant of broad context. It’s one thing to teach a machine to write poetry, but it’s entirely another thing to write poetry that connects with and moves people on an emotional level and speaks to the irrational, emotional and rather messy matter of being a human being. There’s no ‘I’ in AI. There’s no sense of self, no me, no you and no us.

There is some bad news though. An enormous number of current jobs, especially low-skilled jobs, require none of the things I’ve just talked about.If your job is rigidly rule based or depends upon the acquisition or application of knowledge based upon fixed conventions then it’s ripe for digital disintermediation. This probably sounds like low-level data entry jobs such as clerks and cashiers, which it is, but it’s also some accountants, financial planners, farmers, paralegals, pilots, medics, and aspects of both law enforcement and the military.

But I think we’re missing something here and it’s something we don’t hear enough about. The technology writer Nicholas Carr has said that the real danger with AI isn’t simply AI throwing people out of work, it’s the way that AI is de-skilling various occupations and making jobs and the world of work less satisfying.

De-skilling almost sounds like fun. It sounds like something that might make things easier or more democratic. But removing difficulty from work doesn’t only make work and less interesting, it makes it potentially more dangerous.

Remoteness and ease, in various forms, can remove situational awareness, for example, which opens up a cornucopia of risks.The example Carr uses is airline pilots, who through increasing amounts of automation are becoming passengers in their own planes. We are removing not only the pilot’s skill, but the pilot’s confidence to use their skill and judgment in an emergency.

Demographic trends also suggest that workforces around the world are shrinking, due to declining fertility, so unless the level of workplace automation is significant, the biggest problem most countries could face is finding and retaining enough talented workers, which is where the robots might come in. Robots won’t be replacing anyone directly, they will just take up the slack where humans are absent or otherwise unobtainable. AIs and robots will also be companions, not adversaries, especially when we grow old or live alone. This is happening in Japan already.

One thing I do think we need to focus on, not only in work, but in education too, is what AI can’t do. This remains uncertain, but my best guess is that skills like abstract thinking, empathy, compassion, common sense, morality, creativity, and matters of the human heart will remain the domain of humans unless we decide that these things don’t matter and let them go. Consequently, our education systems must urgently move away from simply teaching people to acquire information (data) and apply it according to rules, because this is exactly what computers are so good at. To go forwards we must go backwards to the foundations of education and teach people how to think and how to live a good life.

Finally, circling back to where I started, the Oxford study I mentioned at the beginning is flawed in my view. Jobs either disappear or they don’t. Perhaps the problem is that the study, which used an algorithm to assess probabilities, was too binary and failed to make the distinction between tasks being automated and jobs disappearing.

As to how it’s possible that people can believe that robots and computers will “probably” or “definitely” perform most of the jobs in the future, while simultaneously believing that their own jobs will “probably” or “definitely” be safe. I think the answer is because humans have hope and human adapt. For these two reasons alone I think we’ll be fine in the future.

.

Thought for the Day

In the future people will insure their memories.