It’s done. Oliver and I have sent it off for an edit. If you are interested here’s the intro.

People have always been curious about what lies over the horizon or around the next corner. Books that speculate about the shape of things to come, especially those making precise or easily understandable predictions, have been especially popular over the years. Interest has not diminished of late. Indeed, the number of books seeking to uncover or explain the future has exploded. The reason for this, which ironically no futurist appears to have foreseen, is that rapid technological change has combined with world-changing events to create a future that is characterised by uncertainty and thus anxiety. The world offers more promise than ever before, but there are also more threats to our continued existence.

During the preparation of this book we have seen the sudden collapse of Egypt’s Mubarek regime and the domino affect it has had on the Middle East; the emergent recession in parts of the United Kingdom; the economic plight of Italy, Greece & Spain; the medieval atrocities being perpetrated in Syria; the continuing demise of Barack Obama and the introduction of the iPad which is selling over one million units every month – not to mention 911-style attacks on confidential government and commercial data and John Galliano being caught on a phonecam making racist remarks in Paris.

In short, the future is not what it used to be and needs rescuing. There is now a high degree of volatility in everything from politics and financial markets to food prices, sport and weather and this is creating ubiquitous unease – especially among generations that grew up in eras that were characterised, with 20/20 hindsight, by relative stability and simplicity. A world more like Downton Abbey than Cowboys Meet Aliens!

Thus the interest in books that explain what is going on right now, where things are likely to go next and what we should do about it. But there’s a problem with all these books about the future. Indeed, there’s a fatal flaw with almost all of our thinking about what will happen next. Regardless of our deep desires, a singular future doesn’t exist and there is no heavenly salvation in sight. The present, let alone the future, is highly uncertain and we are even starting to question what happened in the past. At a recent futures summit in Provence, Grigori Yavlinsky, the ex-presidential candidate, admitted to us that the most uncertain thing about Russia was its past. Logically, if the future is uncertain there must be more than one future.

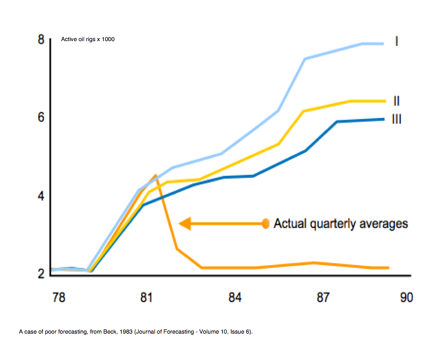

There are, of course, different ways in which the future might unfold and suggesting, as many futurists and technologists do, that one particular future is inevitable is not only inaccurate, but is dangerously misleading. What is worse is when we are asked to assign probability to this future emerging rather than that one. Linear analysis and the extrapolation of current events is a very straight road that promotes directly unforeseen shocks coming from all sides.

As the historian Niall Ferguson has observed: “It is an axiom among those who study science fiction and other literature concerned with the future that those who write it are, consciously or unconsciously, reflecting on the present.” Or as we like to say – all futures are contemporary futures in the same way that all prediction is based upon past experience. This is one reason why so many predictions about the future go so horribly and hilariously wrong.

For example, in 1884, an article in The Times newspaper suggested that every street in London would eventually be buried under nine feet of horse manure. Why would this be so? Because London was rapidly expanding and so too was the amount of horse-drawn transport. Londoners would, it seemed at the time, soon be up horse manure creek without a paddle.

What the writer didn’t foresee, of course, was that at exactly this time the horseless carriage was being developed in Germany by Daimler and Benz and their new invention would change everything. But four years later, in 1898, Karl Benz made exactly the same mistake by extrapolating from the present. He predicted that the global demand for automobiles would not surpass one million. Why? Because of a lack of chauffeurs! The automobile had been invented but the idea of driving one oneself had not. Thus it was inevitable, he thought, that the world would eventually run out of highly skilled chauffeurs and the development of the automobile would come to the end of the road.

The preoccupation with trends analysis is doubly misleading. Not only must trends be lined up with ‘discontinuities’, counter-trends, anomalies and wild cards, which have a nasty habit of jumping into view from left field, they are also retrospective and not ‘futuristic’ at all. A trend is an unfolding event or disposition, which we trace back to its initiation, and trends tells us nothing about the direction of velocity of future events. It is true that occasionally an idea or event occurs that is so significant that history is divided into periods of before and after. The steam engine, the automobile, the microprocessor, the mobile phone, the world wide web, the collapse of the Berlin Wall, 9/11, Google, Facebook and Amazon are all, arguably, examples.

But even here there is confusion. We all have a particular lens through which we see the world and no two individuals ever experience the present in the same way. Moreover, our memory can play tricks. As a result, there is always more than one reality or worldview as we like to call it.

Equally, it is not a binary world. It is a systemic one in which influences making for change interact with each other in complex and surprising ways. It is also a world where it is rare for a new idea to totally extinguish an old idea, especially one that has been in common usage for a very long time. For instance, despite the facility with which mobile technology can deliver ‘media content’, there’s still something reassuring about the daily newspaper dropping with a thud on to the hall mat as we begin another day.

Moreover, while means of delivery, business models, materials, competitors, profit margins and even companies may change radically the deep human needs (e.g. the desire to tell or listen to stories) often remain relatively constant.

Change happens rapidly, but in most instances it takes decades, often generations, for something new to result in a linked extinction event. The slow pace of fast change is observable. We all witness this. Like the destroyer in Sydney Harbour’s Maritime Museum at Darling Harbour – built in 1943 – which has in its ops room a fax machine.

More often than not different individuals and institutions will experience present and future in slightly different ways depending on where they live, what they do and how they have grown up (i.e. more than one reality again). There is more than one present let alone more than one future.

This is a good thing, as is the level of uncertainty that surrounds the future. Indeed, in many respects this is one of the most interesting times ever to be alive, because almost everything that we think we know, or take for granted, is capable of being challenged or changed, often at a fundamental level. Even human nature if Joel Garreau the author of Radical Evolution is to be believed.

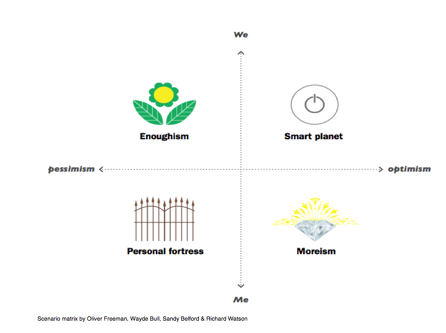

It is the view of the authors of this book that the only rigorous way that one can deal with a future that is so uneven and disjointed is to create a framework that reveals a set of alternative futures covering a number of different possibilities.

This technique, called scenario planning or more properly scenario thinking, originated as a form of war-gaming or battle planning in military circles and was then picked up by, amongst others, Royal Dutch Shell, the oil company, as a way of dealing with ambiguity and uncertainty. In Shell’s case, scenarios correctly anticipated both the 1973 oil crisis, which hiked prices dramatically, and the corresponding price falls almost a decade later.

Other incidences where scenarios have foreseen what few others could include Adam Kahane’s Mont Fleur Scenarios in South Africa in 1992, which foresaw a peaceful transition to democratic rule, and two sets of scenarios created by the authors of this book for a major bank in 2005 and the future of the Teaching Profession in 2006/7, both of which identified futures around the global financial collapse that occurred in 2008/9

This, then, is a book about the future that offers readers a number of alternatives for dissection and discussion. It is not a book about trends, although key trends within demographics, technology, energy, the economy, environment, food, water and geopolitics are commented upon in depth. Equally, it is not a ‘how to’ book about scenario planning, although in the second half of the book the authors explain how scenario planning works and outline how each of the four different scenarios presented in the book were developed. Rather it is a book that considers a number of critical questions and then uses a robust and resilient process to unleash four detailed scenarios about what it might be like to live in the world in 2040 from a variety of different perspectives. It is not simply about where today’s trends might take us but about what the world in 2040 might be like.

It is not our intention to predict the future. We are not seeking, as it were, to get the future totally right. This is impossible. Our aim is rather to prevent people from getting the future seriously wrong. This is achievable, but only if we give ourselves the chance to think bravely and creatively. The book is intended to form part of a deep conversation. It is designed to open peoples’ minds to what is going on right now and create a meaningful debate about some of the choices we face and where some of the things that we are choosing to do – or allowing to happen – right now may go next.

It is intended to alert individuals and organizations to a broad range of longer-term issues, assumptions and decisions and to firmly place a few of them on the long-range radar for careful monitoring and further analysis. It is about challenging fundamental assumptions and re-framing viewpoints, including whether or not people are asking the right questions. And in this context disagreement is a valuable tool.

Most of all, perhaps, we would like liberate peoples’ attitude towards the future. In all our work we discover that people from all kinds of professions and backgrounds want to make a difference – to generate change as well as adapt to it. As Peter Senge once remarked: “Vision becomes a living thing only when most people believe they can shape their future.” So, yes, people need to understand the opportunities and threats that lie ahead but also consider in which direction they would like to travel.

For example, is mankind on the cusp of another creative renaissance, one characterised by radical new ideas, scientific and technological breakthroughs, material abundance and extraordinary opportunities for a greater proportion of the world’s people, or are we in a sense at the end of civilisation, a new world characterised by high levels of volatility, anxiety and uncertainty?

Are we entering a peaceful period where serious poverty, infant mortality, adult literacy, physical security and basic human rights are all addressed by collective action or are we moving more towards an increasingly individualistic and selfish era in which urban overcrowding, the high cost of energy and food, water shortages, social inequality, unemployment, nationalism and increasingly authoritarian government combine to create a new age of misery and rage?

Some urban economists and sociologists are predicting a future in which between one and two billion people will be squatters in ‘edge cities’ attached to major conurbations – Mexico, Mumbai, Beijing and more – while others believe in the concept of a smart planet in which our expertise delivers a triumphal response to the drivers of change and we create local self-managed inclusive communities which resonate with traditional democratic value.

Just what does the future have in store for us? This is what this book aims to find out.