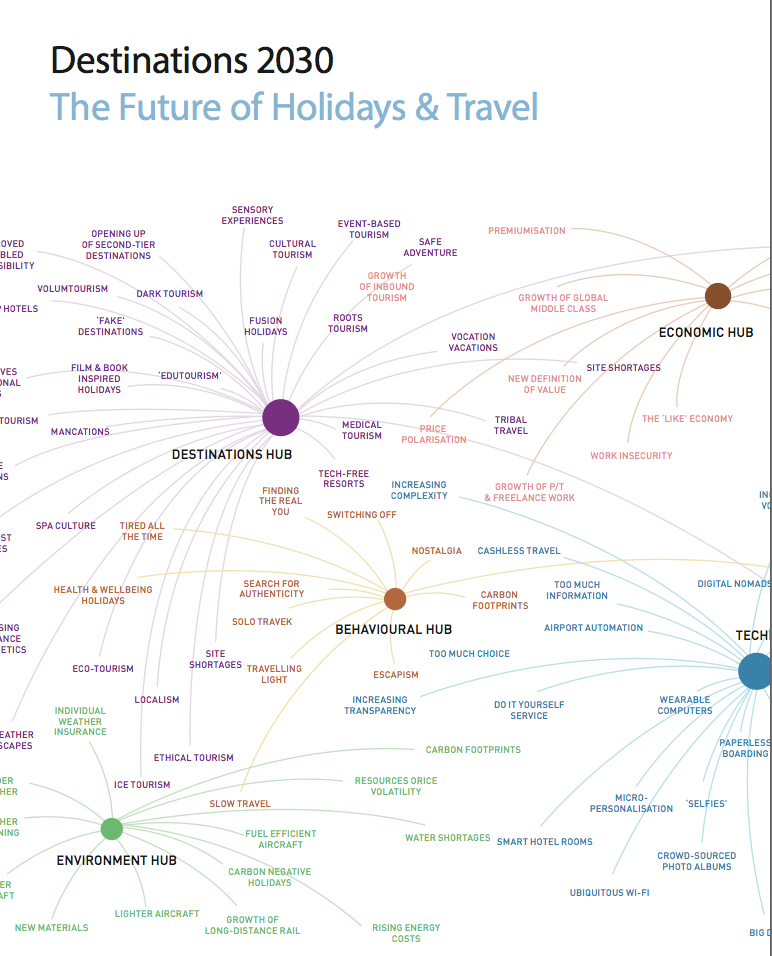

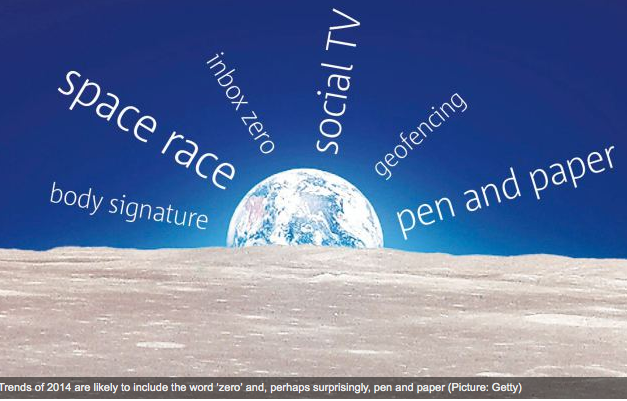

Will the world really look like the chart above in 2050?

One funny thing about predictions is that once someone has made a definitive pronouncement, events often conspire to move things in the opposite direction.

Jim O’Neill, Chief Economist of Goldman Sachs, coined the acronym ‘BRICs’ in a briefing paper issued in London on November 30, 2001. The briefing (Building Better Economic BRICs) described how Brazil, Russia, India and China, all chosen on the basis of population, economic development and attitudes towards globalization, were reshaping the world in terms of economic power. The briefing note also boldly predicted that by 2041 (then revised to 2039) these nations would eclipse the six largest Western nations with regard to economic output. In other words, Russia, Brazil, India and China would soon reshape the world, not only in terms of money, but also in terms of influence and ideas.

Following on from the BRICs we’ve had the Next Eleven countries and now the MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey). But like the BRICs, most if not all of these countries suffer from some fairly fundamental issues relating to governance and corruption, which could bring some or all of them crashing down.

China, arguably, has a building bubble in the making, its financial system is suspect (shades of the Japanese banking system prior to their ‘lost decade’), water is an issue, they are running out of low-cost rural migrants, the country is ageing rapidly and the imbalance of young males in China’s population could cause trouble if economic growth slows and unemployment starts to rise. Meanwhile, Russia is a tinderbox politically and Brazil’s prospects seem to rise and fall all the time depending upon the latest economic numbers and the whims of newspaper and magazine editors. This leaves India, where infrastructure is being pushed to its physical limits and where corruption is endemic.

This leaves the USA in an interesting position. The US is far more resilient than most people realize, thanks to a mix of favorable demographics (a high fertility rate plus a ‘can do’ attitude towards immigration) and cultural factors that include the American Dream and some highly positive attitudes towards innovators and early stage venture capital.

Add all this up and what we might find is that while the BRICs, N11 and MINTs all grow in importance, it will be the US that remains dominant out to 2050.

Image source: IMF/Citibank