Category Archives: Privacy

The right not to be seen

If you are wondering why privacy matters, here’s a great summary by Daniel Solove, A Professor at GW Law School. I hope he won’t mind me copying this here.

1. Limit on Power

Privacy is a limit on government power, as well as the power of private sector companies. The more someone knows about us, the more power they can have over us. Personal data is used to make very important decisions in our lives. Personal data can be used to affect our reputations; and it can be used to influence our decisions and shape our behavior. It can be used as a tool to exercise control over us. And in the wrong hands, personal data can be used to cause us great harm.

2. Respect for Individuals

Privacy is about respecting individuals. If a person has a reasonable desire to keep something private, it is disrespectful to ignore that person’s wishes without a compelling reason to do so. Of course, the desire for privacy can conflict with important values, so privacy may not always win out in the balance. Sometimes people’s desires for privacy are just brushed aside because of a view that the harm in doing so is trivial. Even if this doesn’t cause major injury, it demonstrates a lack of respect for that person. In a sense it is saying: “I care about my interests, but I don’t care about yours.”

3. Reputation Management

Privacy enables people to manage their reputations. How we are judged by others affects our opportunities, friendships, and overall well-being. Although we can’t have complete control over our reputations, we must have some ability to protect our reputations from being unfairly harmed. Protecting reputation depends on protecting against not only falsehoods but also certain truths. Knowing private details about people’s lives doesn’t necessarily lead to more accurate judgment about people. People judge badly, they judge in haste, they judge out of context, they judge without hearing the whole story, and they judge with hypocrisy. Privacy helps people protect themselves from these troublesome judgments.

4. Maintaining Appropriate Social Boundaries

People establish boundaries from others in society. These boundaries are both physical and informational. We need places of solitude to retreat to, places where we are free of the gaze of others in order to relax and feel at ease. We also establish informational boundaries, and we have an elaborate set of these boundaries for the many different relationships we have. Privacy helps people manage these boundaries. Breaches of these boundaries can create awkward social situations and damage our relationships. Privacy is also helpful to reduce the social friction we encounter in life. Most people don’t want everybody to know everything about them – hence the phrase “none of your business.” And sometimes we don’t want to know everything about other people — hence the phrase “too much information.”

5. Trust

In relationships, whether personal, professional, governmental, or commercial, we depend upon trusting the other party. Breaches of confidentiality are breaches of that trust. In professional relationships such as our relationships with doctors and lawyers, this trust is key to maintaining candor in the relationship. Likewise, we trust other people we interact with as well as the companies we do business with. When trust is breached in one relationship, that could make us more reluctant to trust in other relationships.

6. Control Over One’s Life

Personal data is essential to so many decisions made about us, from whether we get a loan, a license or a job to our personal and professional reputations. Personal data is used to determine whether we are investigated by the government, or searched at the airport, or denied the ability to fly. Indeed, personal data affects nearly everything, including what messages and content we see on the Internet. Without having knowledge of what data is being used, how it is being used, the ability to correct and amend it, we are virtually helpless in today’s world. Moreover, we are helpless without the ability to have a say in how our data is used or the ability to object and have legitimate grievances be heard when data uses can harm us. One of the hallmarks of freedom is having autonomy and control over our lives, and we can’t have that if so many important decisions about us are being made in secret without our awareness or participation.

7. Freedom of Thought and Speech

Privacy is key to freedom of thought. A watchful eye over everything we read or watch can chill us from exploring ideas outside the mainstream. Privacy is also key to protecting speaking unpopular messages. And privacy doesn’t just protect fringe activities. We may want to criticize people we know to others yet not share that criticism with the world. A person might want to explore ideas that their family or friends or colleagues dislike.

8. Freedom of Social and Political Activities

Privacy helps protect our ability to associate with other people and engage in political activity. A key component of freedom of political association is the ability to do so with privacy if one chooses. We protect privacy at the ballot because of the concern that failing to do so would chill people’s voting their true conscience. Privacy of the associations and activities that lead up to going to the voting booth matters as well, because this is how we form and discuss our political beliefs. The watchful eye can disrupt and unduly influence these activities.

9. Ability to Change and Have Second Chances

Many people are not static; they change and grow throughout their lives. There is a great value in the ability to have a second chance, to be able to move beyond a mistake, to be able to reinvent oneself. Privacy nurtures this ability. It allows people to grow and mature without being shackled with all the foolish things they might have done in the past. Certainly, not all misdeeds should be shielded, but some should be, because we want to encourage and facilitate growth and improvement.

10. Not Having to Explain or Justify Oneself

An important reason why privacy matters is not having to explain or justify oneself. We may do a lot of things which, if judged from afar by others lacking complete knowledge or understanding, may seem odd or embarrassing or worse. It can be a heavy burden if we constantly have to wonder how everything we do will be perceived by others and have to be at the ready to explain ourselves.

Daniel J. Solove is the John Marshall Harlan Research Professor of Law at George Washington University Law School, the founder of TeachPrivacy, a privacy/data security training company, and a Senior Policy Advisor at Hogan Lovells.

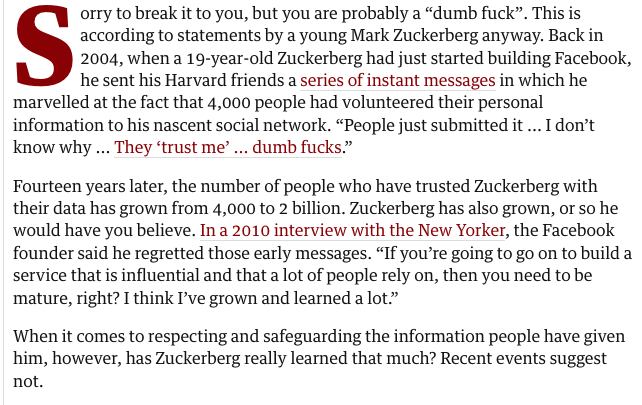

Delete Facebook

The response from Facebook (or rather the complete lack of a response) in light of the Cambridge Analytica scandal is woeful. Only one thing to do. This btw, is from the Guardian and pretty much sums up Zuck’s attitude don’t you think?

Oh, one other thing. Eton. I think the school bears some responsibility for Alexander Nix. Something I wrote last year below…

Another consideration is that, by default, any narrow focus on academic subjects gives certain supposedly intelligent students tacit permission to behave like complete psychopaths at school and later within society at large.

If the system doesn’t value or measure morality or good character then it turns a blind eye to people that don’t have any and who, quite frankly, shouldn’t be let into or out of school in the first place. Under the current system, all that counts is that students pass their exams. What many schools want are kids that achieve high scores, thereby making their own rankings look good. From there ‘successful’ students can move seamlessly into a handful of top universities and thereafter into a select group of organisations. At this point their confidence most likely solidifies into arrogance and their brains go to their heads. Have you met any modest CEOs recently?

An answer to everything?

I’ve just been in San Jose and my head is still in bit of a spin for a number of reasons (one of which is that I essentially went for a day from London).

Anyway, on the way over I read about a UK firm (Analyse Local) offering to use satellite imagery to help councils spot small businesses that are improving their business premises ‘without permission’ and hence potentially subject to higher business rates (not exactly a high crime surely?).

Then a great piece in the San Francisco Chronicle about why tech shouldn’t be used in pre-schools. This is not the first some piece coming out of Silicon Valley that’s anti-tech in schools and rather interesting.

Chimes very much with my chapter on education in Digital Vs. Human and also with something I wrote for the Australian government recently. (Wider discussion about AI here).

Finally, how about this for a head-spinner. How about if you could take everything ever written by humankind, get a computer to read it, and provide an automated summary?

Believe it or not it’s not that hard to do and to some extent we’re doing it already with vast numbers of academic papers (computer reads them all and spits out some insights).

42 anyone?

The on-demand economy

Two interesting conversations last week. The first concerned generational attitudes to privacy. A friend was considering putting their home on Airbnb. His daughter (22) thought it was a great idea. His wife (40 something) was horrified. It exposed differing attitudes to not only privacy but possessions. Ownership Vs. access too. I thought it was interesting.

The second conversation was with a retailer. I had long thought that the new ‘on demand’ economy had a small glitch, which was its business model and economics. Essentially, retailers aren’t making any money on instant (same day) delivery. Customers won’t pay much more than a few pounds to have something delivered on the same day, but it costs more than this to do it. Not sustainable, unless someone can unlock value somewhere or possibly bundle the delivery cost into something else or support it with something else (ads?).

The Future of Privacy

We are currently living in the Technolithic, an age that forms part of the most significant revolution since the agricultural and industrial eras. The Technolithic is part of the information age, but what we are now creating is perhaps not what the early internet pioneers envisaged. In the early days, the internet was about finding information. It is currently largely about finding other people. One day, I hope, it will be about finding ourselves.

But before this can happen we have to deal with a very powerful force, a force that wants to know absolutely everything about us. This force can act for the common good, but can also operate to profit the few.

Who we are and what we are allowed to be, is at the very heart of this. Please don’t get me wrong. I am not calling on you to smash your computers or stop using LinkedIn. All I am asking you to do is to raise your gaze from your freshly picked Apples and Blackberries and to pay closer attention to some of the possible consequences of using these devices, especially the way in which machines and the people that control them appear to be profiting from something that not only belongs to us but defines us.

Digital connectivity has given us many wonderful things and improved our lives immeasurably. At the moment the balance is positive, but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t remain vigilant.

I was in Poland last year doing a TEDx talk and met one of the developers behind an app called Life Circle. This is an app that makes blood donation more effective by opening up the communication lines between blood banks and blood donors. This might sound mundane, but it isn’t. It’s a matter of life in death in some instances. Simply allowing a blood centre to have a users smartphone number means that they can see where their donors are in near real time.

This allows the blood bank to call in certain blood groups if there’s an emergency. It can work anywhere – from Warsaw to Washington – and users can link with social networks and potentially recruit more donors. Moreover, once linked you could potentially ‘game’ blood donation, although the idea of competing with others to see who can give the most blood would obviously be a very bad idea.

Another medical marvel is Google Flu Trends. If you don’t know about it already, it’s an early example of Big Data and near real-time prediction. The story is that some people had a feeling that there must be a correlation between outbreaks of flu in particular regions and search terms used in the same locations. If one could predict the right words you could catch an outbreak sooner.

200,000 people are hospitalised annually in the US alone due to flu and between 20,000 and 30,000 die, but until recently it took the Centre for Disease Control around a week to publish flu data.

The Big Data connection here, by the way, is that Google did not know which handful of search terms would correlate, so it just ran half a billion calculations to find out, and it turned out that 45 search terms were indeed related. What is going on here, and is starting to occur elsewhere too, is that rather than sampling small data sets we are able to look at huge amounts of data, sometimes at all the data in near-real-time, which can reveal correlations that were previously deeply hidden or totally unobservable.

In other words, many aspects of our daily existence that were previously closed, hidden or private are becoming much more open, transparent and public and much of this data has huge value and forms a wholly new asset class.

The website 23andme.com recently got into trouble in the US with the FDA because it was thought by some that the site, and the results of the tests that were being offered, was carrying too much weight and users were acting in ways that were not necessarily in their best interests. In other words, users were seeing probabilities or predictions as certainties.

Again, if you don’t know about this, the site essentially offers to quickly sequence your genome for around $99. A decade or so ago, this would have cost you around a billion dollars. The results might strongly suggest, for example, that a 25-year-old man would have issues with his heart when he was in his 50s or that a 15-year old girl had a significant chance of developing breast cancer.

There are clearly privacy issues galore around new technologies such as these – should your new employer have access to information that you are 70% certain to die in 20 years for example?

Another, more mundane, example of companies looking at people and predicting future outcomes is McDonald’s. They, along with many other fast food chains in the US, have started to use technology to predict what you are about to order – and start to prepare your meal before you have actually ordered anything.

How and why do they do this? In the US about 50% of fast food turnover is through the drive-thru window and customers can become stressed if the queue moves too slowly. CCTV cameras are therefore pointed at cars in the queue and these cameras are connected to software that works out what each car is, not based on individual number plates, but on the silhouette of each car.

This knowledge is then married to millions of bits of historical data about what the drivers of such cars tend to order and, hey presto, predictive sales and marketing. The general idea, I guess, is that if you are driving a 10-year-old Volvo station wagon you’ve probably got a mother and at least one happy meal coming up, whereas if you can see a brand new Hummer you are not about to sell a small salad and a bottle of water.

Is McDonald’s technology intrusive? Does it invade privacy? I don’t think so. If they are stealing anything it isn’t anything of great value. Moreover, you can mess with their minds by riding a bicycle into the drive-thru and ordering two Big Macs and three cokes.

There are many other examples of machines attempting to know us and predict our behaviour. One is called the Malicious Intent Detector and it’s used primarily in airports in the US. This machine also uses cameras connected to software.

The idea here is that body-language can tell us quite a lot about what people are thinking or, more usefully, what they are thinking of doing. Our facial expressions, our eye movements, our clothes, what we are doing with our hands all betray certain things about us.

Indeed as much as 90% of communication is believed to be non-verbal. Combine this thought with skin temperature analysis (sensed remotely), facial recognition, x-rays and software that looks at how our clothes are fitting and you have a fairly good way of finding out whether someone is carrying something they shouldn’t or is intent on doing something that they shouldn’t.

But we can take things further still. Predictive policing is a direct result of better data and better analysis of crime figures. What it is able to do, with astonishing accuracy, is predict not only where, but when crime will take place. If this sounds like the Department of Future Crime in the film Minority Report that’s more or less the idea. It doesn’t identify criminals directly, but does pinpoint potential targets down to 150 square metres on specific days in some cases.

But that’s just the beginning potentially. If one adds developments in remote brain reading we could possibly have a situation where even our inner thoughts are intercepted. The asymmetry of this situation – and indeed of Big Data generally – shifts the balance of power between the state and the individual so we should keep a careful watch on this.

I’ve had my Identity stolen twice, but the benefits of digital transactions still outweigh any negatives. However, if someone were to steal not only my date of birth, address and bank account details, but everything about me, I’d view this rather differently.

Let’s put it like this. If someone came up to you on the street and asked you for personal information would you give it to them? And what if they asked about your daily schedule, your friends, your work, your favourite shops, restaurants and holiday spots?

How about if they wanted to know which books you read, what kinds of meals you like, how much sleep you get and what you searched for online in the privacy of your own home? Would you find that a little unsettling? Would you at least ask why this person wanted this information? And what if they said that they wanted to sell this information, your information, onto someone else that you’d never met. Would you allow it?

This is essentially what’s going on right now with social networks, although I believe it’s about to get far worse. Part of the problem is the mobile phone, although the word ‘phone’ is rather misleading. After all, using a phone to speak to someone is dying out globally. Voice traffic is falling through the floor, while text based communication is going through the roof.

These phones, and there are more than 6 billion + of them now, are broadcasting information about us all of the time, especially if they are smart phones, which increasingly they are. In fact smart phones have been outselling PCs globally since about 2012. In the UK, almost 10% of five year olds now own a mobile phone and by ten-years-of-age, it’s 75%. Eventually, all of these will be smart phones.

Our mobile phones are actually a form of wearable computing and I’d expect wearables to explode over the coming years. I don’t simply mean more people owning more phones, but more people carrying devices that continually broadcast information about us, and this would includes clothing embedded with computers, shoes containing computers, digital wallets and even toothbrushes containing computers. This is broadly the internet of things and it where the problems will really start.

An internet connected toothbrush might seem trivial, ridiculous even, but trust me they are coming. To begin with they will be seen as expensive toys. You’ll be able to download your brushing history or compete with your friends in various dental games. They will form part of the self-tracking or quantified-self movement and will be bought alongside Nike Fuel bands and sleep monitors.

Nothing wrong with this unless your toothbrush data finds its way into the wrong hands. For example, what if dental care was to be refused – or made vastly more expensive – if you had not reached level 3 of the tooth fairy game?

Currently there are roughly 12 billion things connected by the internet. By 2045 some people think this number will be 7 trillion. This means computers and wireless connectivity in every man-made object on earth and a few natural objects too.

Trees with their own IP address? It’s totally possible. And don’t forget that we put ID chips in our cats and dogs so its probably only a matter of time before we start chipping our children too.

Anyway, the point here is that almost everything we do and almost everything we own in the future, will emit data and this data will be very valuable to someone. I rather hope that this someone is us and that we can opt in and out at will, earning micro-payments for the data relating to our activities if that’s what we want.

And this brings me to why privacy is one of the biggest problems in our new electronic age. At the heart of Internet culture is a force that wants to find out everything about you. And once it has found out everything about you and 7 billion others, that’s a remarkable asset, and other people will be tempted to trade and do commerce with that asset.

Does this matter?

I think it matters for three key reasons.

First, people can be harmed if there is no restriction on access to personal information. Medical records, psychological tests, school records, financial details, sites visited on the internet all hold intimate details of a person’s life and the public revelation or sharing of such information can leave a person vulnerable to abuse.

Second, privacy is fundamental to human identity. Personal information is, on one level, the basis of the person. To lose control of one’s personal information is in some measure to lose control of one’s life and one’s dignity. Without some degree of privacy, for example, friendship, intimacy and trust are all lost or, at the very least, meaningless.

Third, and most importantly of all perhaps, privacy is linked to freedom, especially the freedom to think and act as we like so long as our activities do not harm others.

If individuals know that their actions and inclinations are constantly being observed, commented upon and potentially criticized, they will find it much harder to do things that deviate from accepted norms. There does not even have to be an explicit threat. Visibility itself is a powerful way of enforcing norms.

This, to some extent, is what’s starting to happening already with every intimate photograph, and every indelicate tweet being attributable to source, whether the source wants it to be or not.

As Viktor Mayer-Schonberger has pointed out, the possession of data about used to mean an understanding of the past. But, increasingly, the possession of data is starting to mean an ability to predict and control the future.

In the right hands this knowledge will be a tool for great good. But we should remain vigilant, because in the wrong hands this knowledge will be used against us, either to control us or to profit from us in a manner that destroys us as autonomous human beings.

Zuckerberg’s Law

The amount of personal information people are prepared to reveal about themselves – in return for commercial gain or social status – will double every eighteen months.

Just made that up based upon Mark Zuckerberg’s comment that every year people are sharing twice as much information as the previous year.

Surveillance society

This is brilliant. There are now 32 CCTV cameras within 200 yards of the building in which George Orwell wrote “1984.” * But even if we remove these fixed cameras there’s still the fact that 4 billion people are roaming the planet with mobile phones, most of them equipped with cameras. In other words, while Orwell got the constant surveillance part right, he missed the fact that it would be the individuals themselves that ended up being the cameras. Enter the brave new world of crowdsensing…

* Source: Sam Palmisano, CEO of IBM.