Category Archives: Books

What if people really could see the future?

I’ve heard of the CIA and suchlike conducting experiments around everything from mind control (The Men Who Stare at Goats) to Telepathy, but until just now I’d never heard of The Premonitions Bureau, a real life Twilight-zone style bureau set up by the British psychiatrist Dr John Barker and the UK Evening Standard Newspaper’s science correspondent Peter Fairley. A new book by Sam Knight digs into this real-life ‘laboratory’ that dug into facts and checked people claiming supernatural powers or premonitions. Sounds totally nuts, but Dr Barker was a Cambridge educated head of a mental health hospital. In total he looked at 723 premonitions provided by the public, 3% of which he claimed were accurate. Pure chance? Almost certainly. Then again, don’t some animals have the ability to sense things before they happen? (e.g. incoming storms). There’s a big difference between divining meterological events (or water for that matter) and human-driven events such as assasinations or bridge collapses, but never say never in my book.

Colouring in novels

OK, how’s this for how the brain works. I’m writing some powerpoint slides for a presentation and the new version keeps adding titles for any image I insert. I went to bed, obviously subconsciously remembering a point madfe by a sci-fi writer friend of mine called `Lavie Tidhar about illustration being expensive for kids books. I woke with the idea of having blank panels in the book with captions describing the empty space – the implication being that the reader has to imagine for themselves what the image would look like.

I mentioned this to Lavie later and he added “it’s a colouring in novel. ” The kids draw their own illustrations.

How to do nothing

I’ve got sod all on at the moment (thanks Coronavirus!) so I’ve started to read How to do nothing in the greenhouse by Jenny Odell. No…the book is called How to do Nothing… I’m reading it in the greenhouse…got it? I haven’t got very far, but it’s shaping up to be really good book. The quote at the start is fab too, especially in light of what’s going on right now.

Future Shock at Fifty

Here’s my chapter from the new book that’s just out looking back at Future Shock. The book, After Shock, can be bought here. US link here.

Future Shock @ 50.

One of the enduring issues futurists face is bad timing. Like science-fiction writers and technologists, futurists often believe that things will happen sooner rather than later. Future Shock, which accurately described the turmoil of the 1970s, is perhaps more accurate and relevant now than it was then. The book’s central idea, that the perception of too much change over too short a period of time would create instability, perfectly describes the volatility, uncertainty and confusion currently being created by geo-political events, climate change and technology, most of all digital technologies, that accelerate everything except our capacity to cope with change. Hence a global epidemic of anxiety that expresses itself in everything from the rise of mental illness to the mass prescription of painkillers and anti-depressants.

Looking backwards, it’s hard to imagine how the upheavals of the early 1970s could have be seen as shocking. Surely the pace of change then was glacial compared to what it is now? But we have largely forgotten about the seismic shift from ‘we’ to ‘me’ that accompanied the fading of the sixties and the blossoming of the seventies. Group love was replaced by empowered individualism. The invention of modern computing, which soon became personal computing, amplified the focus on the individual even further. Peace, too, was shattered, not only by the enduring war in Vietnam, but by the invention of international terrorism, while OPEC’s oil shock created inflation and economic uncertainty. Oh, and the US had a rogue President, which proves, to me at least, that some things do not change quite as much as we sometimes imagine.

Maybe the speed of change in the 70s wasn’t as rapid as today, but events back then were still alarming compared to the relative stability that had endured before. Global media made such events more visible too. Information Overload is idea championed in Future Shock and another that feels almost quaint when it’s used in the context of the 70s. Overloaded? Way back then? You cannot be serious.

The problem, of course, is that while many things did indeed change, and continue to do so today, we do not. Or, at least, we struggle to keep up. Edward O. Wilson, the American biologist, sums the situation up perfectly when he says that:

“Humanity today is like a waking dreamer, caught between the fantasies of sleep and the chaos of the real world.

The mind seeks but cannot find the precise place and hour.

We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”

This clash, between technologies and behaviours that change rapidly (exponential is a word that’s thrown around with careless abandon, but rarely stacks up outside computing) and our brains which do not change as fast was seen by the Toffler’s as being injurious to not only our health, but to our decision-making abilities too.

Interestingly, decades after Future Shock was written, a study published by Angelika Dimoka, Director of the Centre for Neural Decision Making at Temple University, appears to support part of what the book proposed.

This study found that as information is increased, so too is activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a region of the human brain associated with decision-making and the control of emotions. Yet eventually, if incoming information continues to flow unrestrained, activity in this region falls off. The reason for this is that part of the brain has essentially left the building. When information reaches a tipping point, the brain protects itself by shutting down certain functions. Outcomes include a tendency for anxiety and stress levels to soar and for people to abstain from making important decisions. Not so much future shock as present paralysis, perhaps.

Future Shock did not propose a solution to this problem.

The book, as the authors pointed out, was always more of a diagnosis than a cure, although education is mentioned as a critically important factor going forward. So too is a need to guard against change that’s either unguided or unrestrained.

This, again, is very much where we stand today. Technologies such as autonomous trucks, surgical robots and battlefield drones are being developed with little or no public debate.

If Tesla, for example, were Boeing or Bristol-Myers Squibb, I find it hard to imagine how their products would be allowed anywhere near the public at such a stage of development. As for artificial intelligence, the situation is even worse.

Broad or General AI could be the best or the worst invention humankind will ever make and yet there is hardly any broad discussion about the risks, let alone any public debate about what this technology is ultimately for. Like many other things, AI is largely being imposed upon people for economic gain and it is hard to see why it will enhance rather than diminish our humanity overall. However, this pessimistic view ignores two things I’ve learned about the future, which is that the future is not linear and it’s not binary either. Things will happen that nobody, especially futurists, saw coming and the most likely scenario is an uneasy balance between people wishing to push forwards and others wanting to pull back.

So, fifty years on, is there now a cure for Future Shock?

I think there is and I believe that we are beginning to see some early signs of it.

In my view, the central problem at the moment is not change or acceleration per se, but that we have lost trust in government, science, business, the media and even each other. We’ve also simultaneously lost our anchor points and thrown away our ballast, with the result that we are being tossed about in a high sea without any sign of land to navigate towards. No wonder we are feeling disorientated and somewhat nauseous.

It is this lack of direction, more than anything else, that is fuelling our anxiety in my view. But a simple solution is at hand. First, we need a moderate level of disconnection.

We need to stop treating all information as power and reclaim some control over what enters our brains. The information universe is infinite, but our attention spans and mental processing capabilities are not. More importantly, without a strong sense of identity, in other words a sense of whom we are and where we stand, we will continue to be thrown around by the slightest disturbance.

I’m not for a moment suggesting that we ditch our cell-phones or throw out our televisions in the style of Peter Finch in the movie Network, more than we consider more carefully the ideas that we let into our homes and our brains.

One we have regained some sense of calm and perspective we then need to talk to each other about where it is that we want to go in the future. How do we want to live? Even the ‘fact’ that the future has arrived all at once, which some people cite as being a source for many of our troubles, would be easy to deal with if we only knew what destination we were heading towards. Then, as Future Shock suggests, we could restrain or reject anything that impedes our progress.

Having a view of what lies ahead, a shared vision of a promised land if you will, would also allow us to focus more on the present and worry less about endless unknowns. We should spend far less time individually worrying about what might happen and much more time collectively thinking about what it is that we want to happen.

There are echoes of this happening already in everything from the growing disenchantment with our political elites and Big Tech to the criticisms that are emerging concerning globalisation and the sterile nature of free-market economics and the inequality of wealth and opportunity that results.

In my opinion, the next big thing will be a seismic shift concerning what we value, which is us. All we are waiting for is a trigger. People can feel that something or someone is coming already, although nobody has expressed it yet.

It is the absence of a future, and especially a future where humanity matters, that is being felt, but I believe we are on the cusp of changing things in the right direction.

As Future Shock says, we need to humanize distant tomorrows and the best way of doing this is to take control of the future. Whether we like it or not, we are on the cusp of developing technologies that will give us godlike powers. The simple question is what to do with this power. Who do we, as individuals, societies and a species, want to be?

Alvin Toffler died in 2016, his wife and co-author in 2019, and I think we all owe them a great debt. Not only did they place future thinking firmly on the world’s stage, they established a literary genre that continues to this day.

Richard Watson is the author of Digital Vs. Human and the founder of nowandnext.com

Future Shock 50 Years On

It’s been 50 years since the publication of Future Shock, arguably the most famous non-fiction book ever written about the future. To celebrate, a new book called After Shock is being published next week. I have contributed a chapter, which I will post next week. In the meantime here is a link to a pdf of the original book.

Future Cities

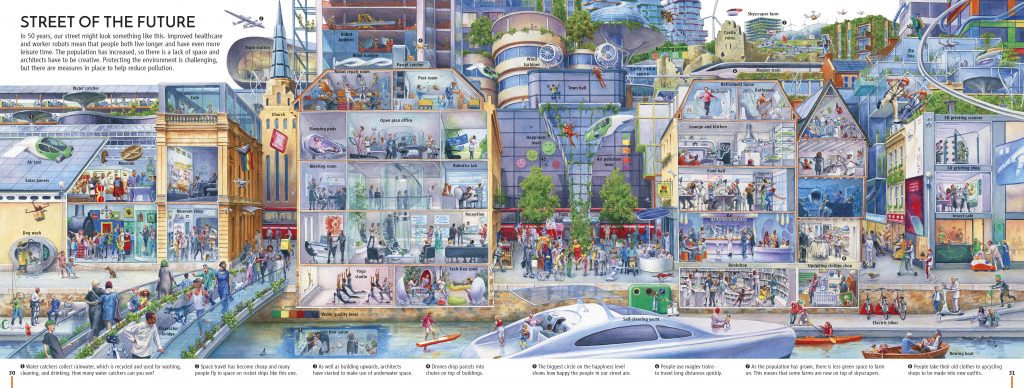

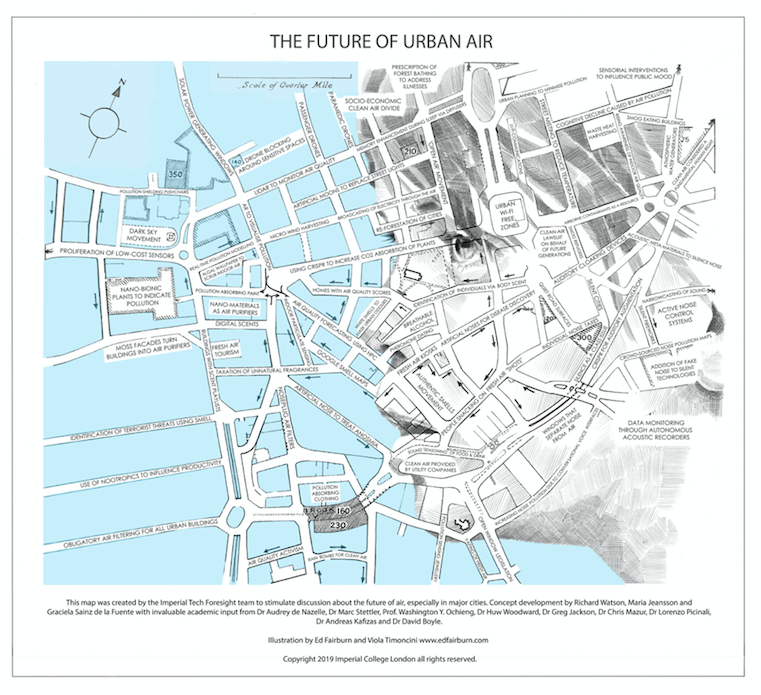

I seem to be carving out a niche with books about the future for kids. I’ve just contributed to a second, the updated version of A Street Through Time, published by DK £10.99. Works well, I think, alongside the future of air map (not really for kids).

Having a bad day

Just got the feedback from the publisher on my new book. Great feedback. But essentially it’s a f%$£@!g re-write. That’s my friend on my right. She’s having a bad day too.

Inevitable Surprises

I don’t know if this will ever make it into a book, but I wrote this over a year ago and given what’s happening with Brexit it’s perhaps worth putting out there…

Chapter 1: Thinking straight

“If we could first know where we are and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do and how to do it. – Abraham Lincoln.

Slowly wind back your mind. To the 23rd June 2016 at 9.00am to be exact. You may have no idea what you were doing on this day, but I think I know what you were thinking, especially if you were living in Europe. I think you were thinking “Yes!”, “No!” or “WTF!!!”

23rd June 2016 was the day that the world woke up to the news that Britain had decided to leave the EU. I was giving a lecture to the leadership team of a bank, and from what I can recall, it was like herding cats in thick fog in the middle of a zombie apocalypse.

The bankers had been caught unawares. They were shocked that Britain had voted to leave. I was shocked that they were shocked. Honestly, had this not always been a yes or no vote? Had there not been two possibilities? I could understand that the decision hadn’t gone the way they’d wanted or expected, but total dead-eyed disorientated disbelief? We will never know exactly what was in these peoples’ heads, but I have a suspicion that the answer to their collective confusion might have been down to a heavy dollop of group think served with a light sprinkling of confirmation bias.

One big problem with achieving even a homeopathic level of success can be that one develops an enduring capacity to believe that your thinking is always correct, that the way you see the world is the same as any other right-thinking person would. Why bother really thinking about anything if you already know the answer? This situation is not helped by education systems that tend to teach that there is one correct answer. Exams generally teach us that things are true or false. They don’t teach maybe or that things depend on other related and frequently fluid factors.

This self-centred certainty, can result in major disagreements between individuals, but also in thinking that’s there’s no need for deep thinking. This tendency can work inside large organisations too. The more successful an organisation becomes the more blasé´ it gets about self-evident ‘truths’ and you can end up with a pyramid of egos, all convinced of their righteousness and all certain that there is little need to look at things differently. Even when due consideration occurs it tends it be short-term and reactive, not long-term and reflective.

There are endless away-days, strategy days and take your shoes off to be more creative days, but these rarely ponder beyond the next 18 months (36-months if you’re very lucky) or question fundamentals (or fundamental questions). Even CEOs, who are supposed to spend a great deal of time thinking about the long view, can get sucked into daily distractions and find it difficult to fix an appointment with themselves to just think.

Hence, what I’d term the unthinking organisation. Such organisations can be likened to reanimated corpses. These are zombie-like organisations that wander around in a mindless manner sinking their teeth into anyone with a different opinion or a free mind.

They are dead from the neck up, although they still manage to have a highly efficient immune system that forcefully rejects any alien thought or new idea. Maybe it’s why the average lifespan of an S&P 500 company in the US has fallen from 67 years in the 1920s to just 15 years today and why 75 per cent of firms in the S&P 500 now will be gone – or going – by the year 2027. These figures come from a study by Richard Foster at the Yale School of Management and echo a similar study from the Santa Fe Institute that found publically quoted firms in the US die at similar rates regardless of age or industry sector.

In the UK, it’s a similarly skeletal story. Of the 100 companies in the FTSE 100 in 1984, only 24 were still breathing in 2012. Nothing recedes like success or so it seems. Why do organisations behave like this? (why do they die like this?). I think it’s because they think they think, but they don’t really. Their thinking is largely tactical and bounded by conventional wisdom. It’s largely about plucking some numbers out of the sky and then working backwards to explain how these numbers will come into being. This can work well for a while, a long while in some instances, but if the wider operating environment becomes complex, volatile and ambiguous it’s usually only a matter of time before what used to work doesn’t any longer. These organisations then get ambushed by what is happening outside of them: specifically, new technologies, new competitors, new business models, new economics, shifting social attitudes and behaviours and geopolitical change.

Why aren’t large organisations in particular more open minded? Some are. The Ministry of Defence in the UK and the Department of Defence in the US both ponder the imponderable, not because they will necessary be 100% right, but because they don’t want to be 100% wrong. Reducing magnitudes of error in combat can literally save lives. But most large organisations don’t do this. They are like super-tankers approaching an iceberg. Having finally decided that an object on the radar is indeed an iceberg, there’s a long discussion on the bridge about the need to turn and at what speed and in which direction. But then it takes ages for the ship to actually turn. It’s all very well talk about organisations ‘pivoting’ but my experience is that most are incapable. The only organisations that can and do change direction rapidly are small start-ups, where again it’s often a matter of life and death.

Exhibit one: Group Think. This idea was first put forward by Yale psychologist Irving Janis in 1973 and sought to explain why groups of smart people often make terrible decisions. The problem, as he saw it, is that groups tend to seek solidarity, harmony and consensus and work actively to supress any form of dissent. This is the main reason, I believe, that the bank mentioned earlier failed to see the possibility of Brexit occurring.

Exhibit two: Confirmation Bias. Groups can display collective confirmation bias, but the term is best applied to individuals and describes the way in which people tend to favour information, data (and individuals) that broadly reflect what they already think or believe.

In other words, we all inhabit echo chambers where our views, opinions and strongly held beliefs are reflected back to us and go unchallenged. Social media has made this far worse, amplifying what used to be a local phenomenon into a global one. Because both these biases, but especially confirmation bias, operate at a subconscious level, blocking any incoming information from reaching our conscious minds, it’s hard to be aware of what’s going on, let alone make allowance for it. In a sense, none of this stupidity is our fault.

To give the bank credit, I understand that they had made mild preparations for a ‘no’ vote in the referendum, but even so it was fascinating to observe how group think, in particular, played out. The bank was based in London. Everyone, more or less, lived close to the capital. Most of the people these people knew also worked and lived near London and probably thought more or less like they did. It was essentially a self-referencing group.

So how might the leadership team have challenged their own thinking? One way might have been to widen their intelligence gathering operations. I imagine that most read publications such as The Banker and probably the Economist (but doubtfully all of it). Probably the Financial Times too. Had they read The Sun or watched Daytime television or listened to talk radio they might have thought differently. Better still, perhaps they could have left their dozy desks and visited some of their own branches outside London.

Speaking directly to staff, and especially to customers, rather than relying on research reports and the media, (the latter again largely located in and focussed on London) may have opened their eyes to the idea that some people thought that local identity might trump global economics. Interestingly, it could be argued that both Brexit and Trump are connected to something else people can’t see, namely ageing populations. The problem here, once again, is that most organisations are staffed by people in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s and it’s hard for them to imagine what’s in the heads of people in their 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s.

So, my lecture wasn’t going quite as expected. But then, to make matters worse, I suggested that Britain might not leave the EU. At this point the leadership team probably decided that I was certifiable. Had we not just voted to go? So how could we possibly stay? Are you nuts? But, of course, impossible is often a matter of opinion. One distinguishing feature of the future is precisely that it’s so vague. It’s always a moving target too. Anyone that thinks otherwise will eventually get run over by reality. In almost any instance you can imagine, there’s always more than one way things can turn out. It’s usually about probabilities, not inevitabilities, but even here we tend to be hopeless at judging the odds.

Not to be continued (as far as I can see).

The book that never was

Not all of my books make it. This is the introduction from a book that’s been junked….

Introduction

“The other day I was thinking, “I just over think things.” And then I thought. “Do I though?” – Demetri Martin, Comedian.

This book is a gentle plea for more thinking. Specifically, it’s an appeal for a calmer, slower, deeper, more reflective, more deliberate and longer-term mind-set in everything from business and politics to holidays and household chores.

I initially thought of calling this book How to Think, but then I instinctively thought that perhaps people don’t want to be told how to think. Surely thinking is an instinctive skill that doesn’t need thinking about. But is this true? Have you ever thought about this?

We aren’t generally taught how to think at school and we don’t think deeply about our thinking very much thereafter. This is a great shame, because our thinking, and especially our imagination, is perhaps the most precious natural resource we’ve got on earth. But it’s being polluted by everything from endless streams of interruption to the unsustainable demands of narrow and numerically-based financial markets. Our liberty to think openly and freely is also being eroded, both by universities supporting ‘no platform’ policies and by the visceral hatred endemic in much of our polarising political culture.

This hasn’t always been the case, and it’s not true everywhere either. But our fixation with doing everything as quickly as possible is making us, our institutions and society infirm. Even weekends and holidays, which were once times for relaxation and reflection, have been invaded by digital devices that demand our constant attention and disconnect us from our true selves. I might be wrong, but the collateral damage of our hyper-connected world might be people that are less connected, both to themselves, and the wider world around them. Our mental focus, like our education systems, is shrinking when it should be expanding. We need to bring back breadth, depth, lifelong wonder and curiosity.

There have been a number of books about the neuroscience of thinking, especially how our sly subconscious gets us into so much trouble. We are surrounded by the debris of this on a daily basis. We rush into roles, responsibilities and relationships without properly thinking, or we think about things in a singular, linear and unconnected manner. We ignore the layered lessons of history, the cyclical nature fashion and the counter-forces that often emerge in response to any significant innovation or event.

Books about creativity and innovation abound too, but these tend to exist within a sterile vacuum divorced from real world pressures, organisational psychologies and institutional pathologies. Have you tried really thinking at work? Without permission? For a whole day? Without getting reprimanded? Or what of the impact of mood on thinking? Why don’t we think about this more often? Why are we so careless with the physical environments in which we expect our co-workers to think and our children to learn? Why is our obsession with external architecture so often to the exclusion of the other sensory elements, for example the architecture of touch, sound and smell?

On all counts, the result is thinking that’s becoming increasingly timid, lazy, sterile and one-dimensional, which is making us open to unmanageable surprises.

I would like to address all these issues and more, but from a positive perspective. I am less concerned about why things go wrong and more interested in how to put them right. How can we manipulate our meddlesome minds to make them more attuned to emerging opportunities and risks? How can we become more sensitive to the faint murmurs that are so often the forerunners of change? How should we embolden individuals and organisations alike to filter out utter nonsense, spot valuable anomalies or realise the significance of an overheard anecdote? How, for instance, might an organisation use smell to increase productivity?

Most importantly, we are possibly on the cusp of a radical revolution in artificial intelligence and advanced machine learning. How might we educate our minds – and those of our children and our children’s children – to be open, adaptive and resilient in disruptive environments? How should we think when machines can do this for us? How can we ensure that one of the major consequences of machines that can think isn’t people that don’t or needn’t? How do we guard against a situation where human complacency or disenfranchisement means we no longer ask questions like these?

I think the answer to this is to become very good at the things these machines are very bad at. In short, we must work tirelessly to unleash our unique ability to think imaginatively, ethically and empathetically and inspire others to do the same. And to do all this, and much more besides, I believe we need a moderate level of disconnection and a significant amount of time. Without this no stable sense of self can emerge. Only when we are firmly anchored in ourselves can we hold conversations from which new ideas and insights will emerge. Only when we achieve a graceful, joyous, lightness of being can we float above our everyday existence and correctly perceive, and solve, the global challenges that lie ahead.

We cannot construct a long-term strategy for human accomplishment, let alone one for the survival of our species, when we are smothered by busyness, distracted by ephemera or constantly running to keep up with the accelerated present.

Sit down, turn off your phone, switch on your attention and come with me for a gentle stroll down some hidden paths of perception and possibility.