I know I’m not supposed to be reading newspapers, but when I find one left on a train I sometimes flick through.

Anyway, I’m getting increasing concerned by the removal of people. First it was the supermarket (and what a sterile, soulless, joyless place that now is), then it was my bank (no cashiers now, just terminals, with one overworked person with an iPad endlessly explaining to people over the age of 40 (you know, the ones with all the money) why they now have to deal with machines rather than human beings. Above is the latest example.

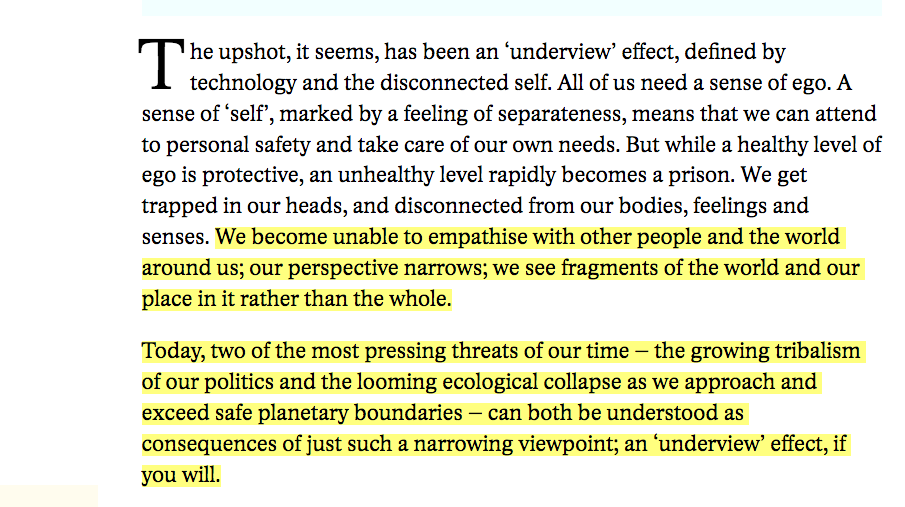

In theory this might be a good idea. Another channel to contact the police. But we all know what’s going to happen. Mission Creep. It will save the Met a load of money and will eventually be the only way you can contact the police. God forbid your phone gets lost or runs out of battery. And how exactly is an online police station going to provide empathy or reassurance?