“Google knows everything” – Nick, aged 8.

This is a book about how the digital era is changing our minds. It is about how new digital objects and environments, such as the internet, mobile phones and e-books are re-wiring our brains — at home, at work and at play.

Technology clearly has a lot to do with this, although in many instances it is not technology’s fault per se. Rather it is the way that many trends are combining and technology is either facilitating this confluence or accelerating and amplifying the effects. This may sound alarming but it needn’t be. We have created these digital technologies using imagination and ingenuity and it is surely within our grasp to decide how best to use them — or when not to.

But can something as seemingly innocent as a Google search or a mobile phone call really change the way that people think and act? I believe they can — and do.

This thought occurred to me one morning when I was looking out into space, from the rooftop of a hotel in Sydney. But then I reflected. Would I have thought this if I were on the phone, looking at a computer screen, in a basement office in London?

I think the answer is no. The hotel was a calm and relaxed environment with expansive harbour views, whereas an office can be a box of digital distractions. Modern life is indeed changing the quality of our thinking, but perhaps the clarity to see this only comes with a certain distance or detachment.

Does this matter? I think it does. Mobile phones, computers and iPods, have become a central feature of everyday life in hundreds of millions of households around the world. There are currently more than one billion personal computers and more than four billion mobile phones*(1) on the planet. In 2005, 12% of US newlyweds met online, while kids aged 5-16 years of age now spend, on average, around six hours every day in front of some kind of screen. This technological ubiquity must surely be resulting in significant attitudinal and behavioural shifts — but what are they? The answer is that nobody is really quite sure. The technology is too new (the internet is barely 5,000 days old) and our knowledge of the human mind is still too limited.

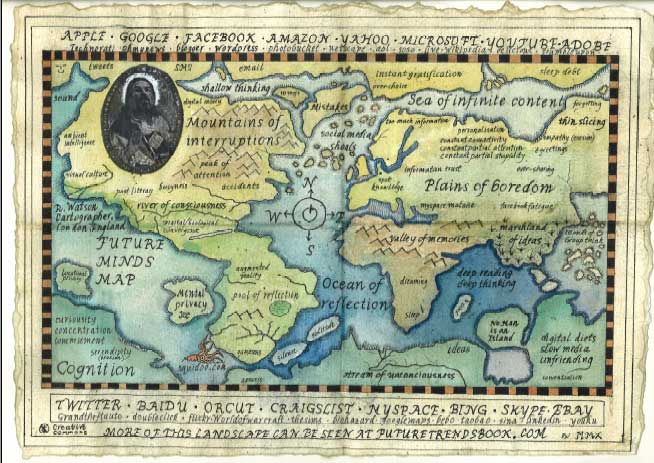

We do know the human brain is ‘plastic.’ It responds to any new stimulus or experience. Our thinking is therefore framed by the tools we choose to use. This has been the case for millennia but we have had millennia to consider the consequences. This has arguably changed. We are now so connected though digital networks that a culture of rapid response has developed. We are so continually available that we have left ourselves no time to properly think about what we are doing. We have become so obsessed with asking whether something can be done that we have left no time to consider whether something should be done. Perhaps the way our brains are constructed means that we just can’t see what is going on.

Moreover, the digital age (the internet, search engines and screens in general and mobile phones and digital books in particular) is chipping away at our ability to concentrate. As Professor Mark Bauerlein, author of The Dumbest Generation points out, screen reading “conditions minds against quiet, concentrated study, against imagination unassisted by visuals, against linear sequential analysis of texts, against an idle afternoon with a detective story and nothing else”. We are therefore in danger of developing a new generation that has plenty of answers but few good questions. A generation that is connected and collaborative but one that is also impatient, isolated and detached from reality. A generation that is unable to think in the ‘real’ world.

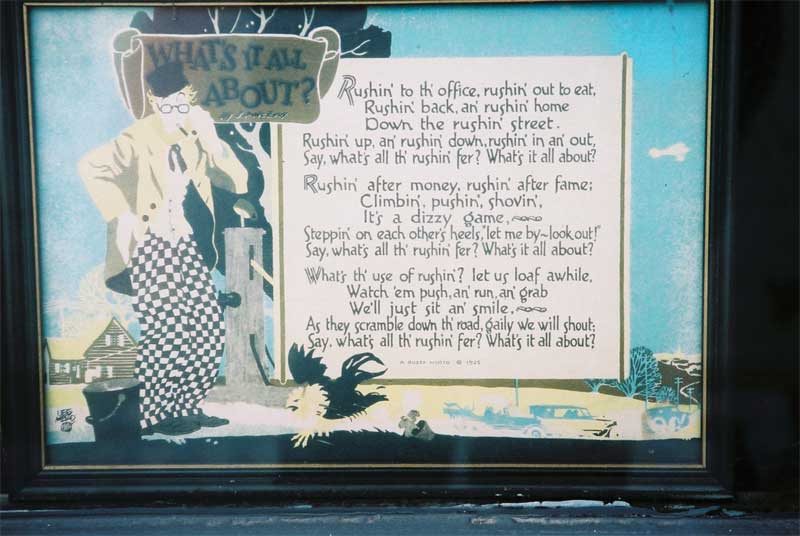

It’s not just the new generations either. We all scroll through our days without thinking deeply about what we are really doing or where we are ultimately going. We are turning into whirling dervishes, frantically moving from place to place in search of superficial ecstasy, unaware that many the things we most yearn for are being trampled by our own feet. It is only when we stop moving and the dust settles that we can see this destruction clearly. Our attention and relationships are becoming atomised too. We are connected globally, but our physical relationships are becoming wafer thin and ephemeral. Digital objects and environments influence how we all think and are profoundly shaping how we interact.

Ultimately, I believe the quality of our thinking – and ultimately our decisions – is suffering. Digital devices are turning us into a society of scatterbrains. If any piece of information can be recalled at the click of a mouse, why bother to learn anything? We are all becoming google-eyed. If GPS*(2) can allow us to find anything in an instant, why master map reading? But what if one day the technology doesn’t work? What then?*(3)

It is the right kind of thinking – what I call deep thinking – that makes us uniquely human. This is the type of thinking that is associated with new insights and ideas that move the world forward. It is thinking that is rigorous, focused, deliberate, independent, original, imaginative and reflective. But deep thinking like this can’t be done in a hurry or in an environment full of noise and interruptions. It can’t be done in 140 characters or less. It can’t be done when you are doing three things at once.

Yes it’s possible to walk and chew gum at the same time but I am concerned about what happens when you add a Twitter stream, a Kindle and an iPod into the mix. In short, what happens to the quality of our thinking when we never really sit still or completely switch off?

Why does all this matter? Because a knowledge revolution is replacing human brawn with human brains as the primary tool of economic production.*(4) It is now intellectual capital (i.e. the product of human minds) that matters most. But we are on the cusp of another revolution. In the future, our minds will compete with smart machines for employment and even human affection. Hence, being able to think in ways that machines cannot, will become vitally important. Put another way, machines are becoming adept at matching stored knowledge to patterns of human behaviour, so we are shifting from a world where people are paid to accumulate and distribute information to an innovation economy where people will be rewarded as conceptual thinkers. Yet this is precisely the type of thinking that is currently under attack.

So how should we as individuals, organisations and institutions (the latter being those deliberately built environments where we spend most of our lives) be dealing with the changing way that people think? How can we harness the potential of new digital objects and environments whilst minimising their downsides?

Personally, I think we need to do a little less and think a little more. We need to slow things down. Not all the time but occasionally. We need to stop confusing movement with progress and get away from the idea that all communication and decision making has to be done instantly. The tyranny of the next financial quarter is just as damaging to deep thinking as a noisy office fitted with fluorescent lighting.

I’m sure that by writing this book I will be accused by some people of going backwards, or of being a pastist. But remember that some of the tried and tested technologies of yesteryear have grown old precisely because they are good and we should think twice before deleting them. Equally, being a member of the Tech No movement doesn’t mean smashing the nearest digital device. It simply means questioning potential consequences or asking for some level of balance. It is about arguing that we need a little more of this and a little less of that.

This is a book about work, education, time, space, books, baths, sleep, music and other things that influence our thinking. It is about how something as physical, finite and flimsy as a 1.5 kg box of proteins and carbohydrates can generate something as infinite and potentially valuable as an idea. Hence, it is for anyone who’s curious about thinking about their own thinking and for everyone who’s interested in unleashing the extraordinarily potential of the human mind.

Whether you are interested in how to deal with too much information, constant partial attention, our obsession with busyness, leisure guilt, the myth of multi-tasking, the sex life of ideas, or the rise of the screenager, this book explores the different aspects of how digital objects and environments are re-wiring our brains – and makes some practical suggestions about what we can do about it.

—

* (1)Half of British children aged between 5 and 9 now own a mobile phone. For 7 to 15 year-olds the figure is 75%. This is despite government advice that no child under-16 should be using one. The average age that children in the UK now acquire a mobile phone is 8 years.

* (2) I interviewed someone for a job recently and one of her questions was whether or not she could use my car. I said she could, so she asked whether my car had a GPS in it. It doesn’t. She turned the job down. I wish her luck, whatever direction her life goes in. The point here is that GPS and Google give us information but they do not impart understanding and in some cases they can prevent us from properly planning ahead.

*(3) We assume the internet will always work. But what if it doesn’t? A US think-tank (Nemertes Research) says internet use is rising by 60% each year worldwide. Unless we can increase capacity they claim ‘brownouts’ (frozen screens, download delays etc) will become commonplace, relegating the internet to the status of a toy. How would you cope with that?

* (4) A study by McKinsey & Company, a management consultancy, claims that 85% of new jobs created in the US between 1998 and 2006 involved “knowledge work”.