Did I mention this one? Written by my mum in 1966. Coming soon….

It strikes me that if you want to spot trends or engage with the zeitgeist a good way to start is to look at what people are reading, watching or listening to. A good example is the recent US best seller book list. Top of a recent list were a biography of Elon Musk and the story of the Wright brothers. What can we make of this? Possibly that the US is thinking about invention and new technology, but also that it is looking backwards to an era of great achievement and invention.

It strikes me that if you want to spot trends or engage with the zeitgeist a good way to start is to look at what people are reading, watching or listening to. A good example is the recent US best seller book list. Top of a recent list were a biography of Elon Musk and the story of the Wright brothers. What can we make of this? Possibly that the US is thinking about invention and new technology, but also that it is looking backwards to an era of great achievement and invention.

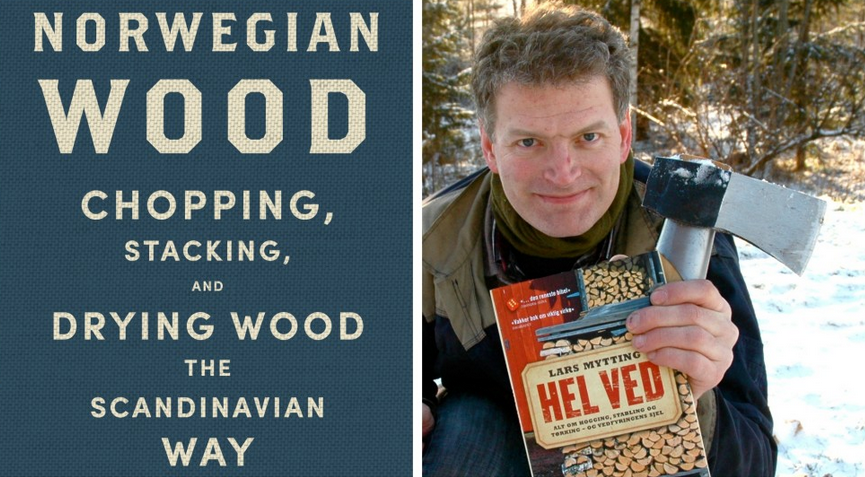

More interesting though is a book about wood (not in the list, but I’d predict a Christmas best-seller for 2015). I’m no Rorschach test expert, but I think this book might possibly tap into or illustrate a general mood. The book in question is Norwegian Wood: Chopping, Stacking and Drying Wood the Norwegian Way by Lars Mytting. Huh?

I think the reason this book is being picked up is twofold. Most fundamentally, this book is a reaction to a crisis of masculinity. Same with beards – are there any beard books? Second, it is symbolic of a human need to disconnect and engage with nature using our hands. That’s what I think anyway.

Just going on a tour of the science fiction library at Imperial College. Coincidently, I’m getting rather interested in acquiring original copies of old books that consider the future. Sci-fi obviously, but there are also a good number of non-fiction works around. For example, I’ve just ordered a copy of Looking Backwards 2000-1887 by Edward Bellamy for the crazy low price of £12.95. A notable idea contained within this book is the concept of “Universal Credit” – a card that would allow future citizens to carry a card rather than cash, which allowed for purchases of various goods and services.

I’ve just (almost) completed some scenarios for the future of gaming so I’m back in the office scribbling like a demon. The latest scribble is a map of emerging technologies and it occurs to me that I am never happier than when I’ve got a sharp pencil in my hand and a large sheet of white paper stretching out in front of me.

Thinking of this, there was an excellent piece this time last year (22/29 December 2012) in the New Scientist on the power of doodles. Freud, apparently, thought that doodles were a back door into the psyche (of course he did – a carrot was never a carrot, right). Meanwhile, a study by Capital University suggests that the complexity of a doodle is not correlated in any way with how distracted a person is. Indeed, doodling can support concentration and improve memory and understanding. Phew.

While I’m on the subject of paper by the way, there’s an excellent paper on why the brain prefers paper in Scientific American (issue of November 2013). Here are a few choice quotes:

“Whether they realise it or not, people often approach computers and tablets with a state of mind less conductive to learning than the one they bring to paper.”

“In recent research by Karin James of Indiana University Bloomington, the reading circuits of five-year-old children crackled with activity when they practiced writing letters by hand, but not when they typed letters on a keyboard.”

“Screens sometimes impair comprehension precisely because they distort peoples’ sense of place in a text.”

“Students who had read study material on a screen relied much more on remembering than knowing.”

OK, this looks good. You should all know about Douglas Rushkoff. He’s a commentator on technology and society, but unlike me he’s really clever. So what is he arguing about in this new book? I’m not sure. It’s not out quite yet in the UK, but the publisher puts it like this (apologies, this is a blatant cut and paste):

“Rushkoff argues that the future is now and we’re contending with a fundamentally new challenge. Whereas Toffler said we were disoriented by a future that was careening toward us, Rushkoff argues that we no longer have a sense of a future, of goals, of direction at all. We have a completely new relationship to time; we live in an always-on “now,” where the priorities of this moment seem to be everything. Wall Street traders no longer invest in a future; they expect profits off their algorithmic trades themselves, in the ultra-fast moment. Voters want immediate results from their politicians, having lost all sense of the historic timescale on which government functions. Kids txt during parties to find out if there’s something better happening in the moment, somewhere else.

Rushkoff identifies the five main ways we’re struggling, as well as how the best of us are thriving in the now:

1. Narrative collapse – the loss of linear stories and their replacement with both crass reality programming and highly intelligent post-narrative shows like The Simpsons. With no goals to justify journeys, we get the impatient impulsiveness of the Tea Party, as well as the unbearably patient presentism of the Occupy movement. The new path to sense-making is more like an open game than a story.

2. Digiphrenia – how technology lets us be in more than one place – and self – at the same time. Drone pilots suffer more burnout than real-world pilots, as they attempt to live in two worlds – home and battlefield – simultaneously. We all become overwhelmed until we learn to distinguish between data flows (like Twitter) that can only be dipped into, and data storage (like books and emails) that can be fully consumed.

3. Overwinding – trying to squish huge timescales into much smaller ones, like attempting to experience the catharsis of a well-crafted, five-act play in the random flash of a reality show; packing a year’s worth of retail sales expectations into a single Black Friday event – which only results in a fatal stampede; or – like the Real Housewives – freezing one’s age with Botox only to lose the ability to make facial expressions in the moment. Instead, we can “springload” time into things, like the “pop-up” hospital Israel sent to Tsunami-wrecked Japan.

4. Fractalnoia – making sense of our world entirely in the present tense, by drawing connections between things – sometimes inappropriately. The conspiracy theories of the web, the use of Big Data to predict the direction of entire populations, and the frantic effort of government to function with no “grand narrative.” But also the emerging skill of “pattern recognition” and the efforts of people to map the world as a set of relationships called TheBrain – a grandchild of McLuhan’s “global village”.

5. Apocalyptic – the intolerance for presentism leads us to fantasize a grand finale. “Preppers” stock their underground shelters while the mainstream ponders a zombie apocalypse, all yearning for a simpler life devoid of pings, by any means necessary. Leading scientists – even outspoken atheists – prove they are not immune to the same apocalyptic religiosity in their depictions of “the singularity” and “emergence”, through which human evolution will surrender to that of pure information.” (ends).

Apocalyptic. I like that. It feels like that. It feels like we are on the edge, teetering, like the end sequence in the movie the Italian Job. And the funny thing is…I think quite a few people, me included, would on one level like the bus to fall off the cliff.

Been in Austria. Reading (properly this time) Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. This was written in 1985 so it’s now rather interesting in the context of the internet and mobile devices rather than TV. Also reading 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense: The Most Intriguing Scientific Mysteries of Our Times by Michael Brooks.

BTW, nice quote…

“Love. Fall in love and stay in love. Write only what you love, and love what you write. The key word is love. You have to get up in the morning and write something you love, something to live for.” –Ray Bradbury,

I’ve been in Greece doing some stuff. The hotel was very nice, but to be frank it could have been anywhere. Interestingly, the guests were largely American, although that’s probably because the hotel was linked to a large American chain. The BRIC tourist crowd that I usually bump into was nowhere to be seen, except for a few young Russians.

The journey out was awful. Because I wanted a direct flight I ended up going with Thomas Cook, which was beyond dreadful. It wasn’t so much the 8-hour delay, but the fact that nobody ever bothered to make an announcement about what was going on. The airport departures board continually displayed incorrect information (3, possibly 4, factually incorrect statements about boarding and departure times) and to find out what was actually happening you had to find the information desk (no signage whatsoever) and even then you ended up talking with a handling agent, not Thomas Cook.

My only explanation for this is that representatives of Thomas Cook were too scared to make an appearance in front of their own customers. You probably think I’m exaggerating this point, but when the final announcement about whether the plane had been fixed or not was about to be made 5 policemen turned up to keep the peace – in case the news was bad. Actually that’s one thing I’ve started to notice about the English – that they no longer sit quietly and do nothing, but complain loudly like Americans.

But what really got me was this. If the company had the foresight to arrange for the police to be present (armed, by the way, although this was a pure coincidence) then why did they not have the intelligence to handle the whole situation better?

What people wanted was information. They wanted someone from the company to show up in person and explain to them what was going on as soon as things looked bad (so within an hour of the missed departure time). If this meant saying that they didn’t know what was going on that would be fine.

Moreover, announcements that certain things would happen at certain times were just plane stupid if they then didn’t. I can understand (but only just) the fact that the departures board continually displayed incorrect information, because there was, I was told, a third party involved. However, people that explain, in person, that |”You’ll be off by 12,00”…“You’ll be boarded at 2.10” or ‘We can load the whole plane in fifteen minutes” should know better than to make promises they can’t necessarily keep.

Customer service moral: Tell people what’s going on directly as soon as there’s a major problem and don’t say things you know not to be true or things that may turn out not to be the case. I get on a lot of planes and I’ve never seen one carrying several hundred people boarded in 15-minutes, for example.

Also, when you apologise to a planeload of angry customers, do it from the heart and not from a soulless script. “We’re sorry for the delay” is a perfectly good response if a plane is 15-30 minutes late. If a departure is 8 hours behind schedule it just won’t do. “We’re incredibly sorry for the huge delay” might be a little bit better. Equally, offering passengers “One free drink” isn’t really appropriate. Do what Virgin Blue once did and say: “All drinks are on us until the bar runs dry”.

BTW, I’ve got two book recommendations for you. The first one is called Why You are Australian by Nikki Gemmell. It’s a letter from the author to her children about why she moved then from England to Australia and it’s terrific.

The second book, that I picked up on impulse at the airport, is called future Babble: Why expert predictions fail – and why we believe them anyway by Dan Gardner. I’m still reading it but so far so good.

A nice quote from Stewart Brand, reviewing a book by George Dyson called Turing’s Cathedral: “One of the best ways to comprehend the future of something is to study its origins deeply.”

I couldn’t agree more. I worked with a newspaper many years ago looking at delivering tomorrow’s newspaper and a vital element was looking backwards one hundred years or so using an historian.

Two books I like the sound of. The first is Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain. Essentially this is about the transition from an age of character (actions) to one of personality (style) where the pressure to entertain and sell oneself (and never to be nervous or unsure about oneself) is growing rapidly. Here’s the central idea of the book: “Introverts living under the extrovert ideal are like women living in a man’s world, discounted because of a trait that goes to the core of who they are.”

The second is It Was a Long Time Ago and It Never Happened Anyway by David Satter. This is about Russia, its lost utopia, its nostalgia for community spirit, its demographic crisis and the rise of Putin. My take from reading a review of this book is that Russia is now primarily about lost empire and a desire to be feared.

A stat from the book (could have been another one on Russia, I can’t remember): When the Soviet Union fell apart its population stood at 150 million. By 2025 it will be between 121 million and 136 million according to the UN.

In its last fiscal quarter, Apple sold more iPhones (37m) than babies were born in the world (36.3m). So, given that Apple products are now so popular, when will someone design a virus specifically targeting, say, iPhones?

BTW, I like the sound of this book (left). Wait: The Art and Science of Delay by Frank Partnov.

And, yes, I’ve also just noticed that I blogged the Apple stat a few weeks ago!