Oh that’s where my crystal ball went…I’ve been looking for it for ages.

Shifting Realities – Tech Foresight 2038

I usually speak on the future at conferences, so it’s a nice change to spend some time crafting presentations for other people. This event is on 14th June and there are some places available. See below for an overview and event link.

Enter the world of 2038, where things are not always what they seem to be, and where technological breakthroughs could change the way we enganige with and see the world.

Tech Foresight 2038 will bring industry leaders together with our world-class academics to unravel the impact of technological advances 20 years in the future.

Book your place to explore a shifting reality brought on by computer-assisted synthesis, nanophotonics, artificial scientific discovery, new data approaches, 4D printing and nutrition futures.

Why not?

Brainmail on the Blog

What can I say? I truly didn’t know that in this age of too much inforation so many people would care. At one point I had a tear in one eye (why only one will forever remain a mystery). So for all those loyal readers who trust LinkedIn (aka Microsoft) about as much as Mark Zuckerberg here is where you’ll find future issues. The next issue (105 I believe) will go up in a few weeks. Maybe. The format is still a bit unclear, but the intent remains much the same. I’d like it to be printable, but I think some experiments might be in order.

In the meantime, here is a picture of the dog enjoying a pint.

The Future of Pensions

Here are 4 futures for pensions. Key takeaway is that the state will most likely move away from pensions provision and so will employers – which leaves things firmly at the feet of individuals, most of whom seem to ignore the issue until it’s too late. Delayed gratification is obviously saving and instant gratification is obviously spending. Lots wrong with this, but it does create a starter conversation.

What assumptions have been made here? One assumption could be that societal ageing and a declining birthrate are fixed trends. What if they aren’t? What if people start dying really young again due to diet/lack of exercise or people suddenly decide to have lots of children again (to care for them in their old age perhaps)?

Another assumption might be that people are saving right now but not in ways that pensions experts recognise as being saving.

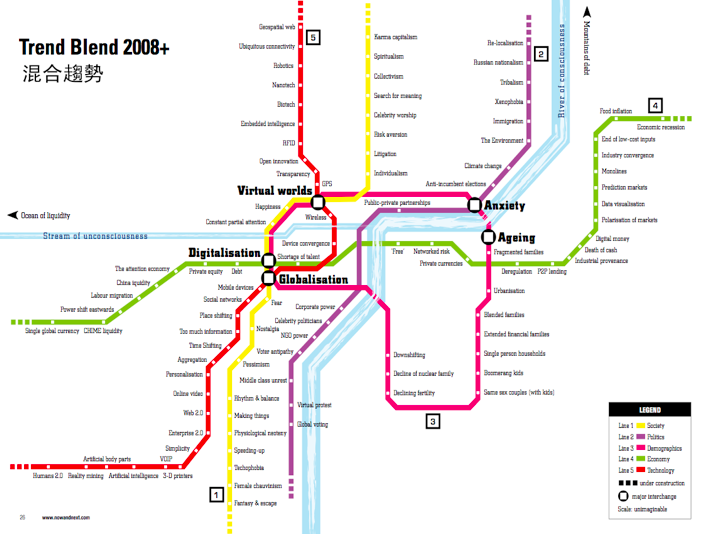

Trends 10 Years On

Not bad!? High resolution download here.

BTW, hello brainmail readers. The response to the deletion of brainmail was so heartfelt that I’m seriously considering carrying on in some form here on the blog.

Things That Won’t Change

Things do not change, we change.

– Henry David Thoreau.

We are constantly told that change is the only constant. This is true, up to a point. Things evolve and we flatter ourselves if we think that anything remains static forever. No man ever steps into the same river twice for it is not the same river and he is not the same man – or something along those lines (Heraclitus, 500 BC). Having said this, one could argue that the really important things in life do in fact change very slowly or not at all and we constantly overestimate the importance of new inventions at the expense of older ones. Consequently, the things that do change are not important.

Here then are five things that I believe won’t change over the next half-century. If this list doesn’t float your boat, I suggest that you look at the seven deadly sins. These haven’t changed much in over two thousand years.

1. An interest in the future and a yearning for the past

People were interested in the future well before Nostradamus. Indeed, the desire to look around the corner or over the garden fence is almost hard wired into the human character. We are curious and what’s going to happen next, partly because we want to avoid risk and partly because we seek opportunity.This interest in the future will not change in the future. In fact I’d predict that the level of interest in future studies will increase as change and uncertainty reach epidemic proportions. So is there a future in becoming a futurist? The answer (I’d predict) is yes, at least for a while. Machines are becoming competent at making numerical forecasts, but we still need humans to ask the questions and interpret what the numbers really mean. In an era of uncertainty we will need prophets, even false ones.

A desire for recognition and respect

People have always craved happiness, recognition and respect. At the extreme this means a yearning for status and power, which in turn fuels a desire for symbols of success. None of this will change in the future, although I would expect that the types of power people crave and the objects people aspire to own and be seen to own will change. For example, children (especially lots of children) may become a status symbol in some cultures with a twin baby buggy having the same social cachet as that of a two-seater Ferrari today. Equally, not owning a watch or a mobile phone may signify wealth in a stealth kind or way – or at least signal that you don’t need to work, which may be much the same thing. Whatever the symbols, the aspiration for recognition and respect isn’t going away.

The need for physical objects, encounters and experiences

We are a social species and the majority of people need physical contact with other people. This will not change in the future, although more of us will live and work alone. Indeed, the more that life speeds up and becomes virtual the more people will crave the opposite – physical interactions with human beings. People who live alone will crave the sensation of being held and touched, but so too will people in relationships. It will be a similar story with physical objects. The more that products and services become virtual the more that people will crave real physical spaces. Equally, the more that high technology becomes ubiquitous the more that people will crave for the old ways of doing things, especially if the rest of their lives are dominated by the insubstantial, the intangible and the impermanent. Hence arts and crafts and making things with your hands (e.g. gardening or bread baking) will flourish in the future.

4. Anxiety, fear and insecurity

When the telephone was demonstrated in 1876, some people thought that the devil was somehow on the line. The reaction to the automobile, the telegraph and even movies created a similar reaction amongst some people. Thus our current fears about the internet or virtual worlds have an historical precedent and it will be no different in the future. We will continue to invent things that make us uneasy and be unsettled and worried about the speed of change. We will therefore want to go backwards in time (or forwards into the future) because historic visions of the past and future will somehow feel safer and more certain. I expect anxiety will accelerate and deepen too, in the sense that future fears will be networked globally. The only solution, ironically, to this insecurity will be our enduring sense of hope and our ability to change.

5. A search for meaning

According to Abraham Maslow’s paper called A Theory of Human Motivation, once an individual’s basic biological needs (food, water, sleep etc) have been met they seek to satisfy a number of progressively higher needs. These range from safety through love and belonging to status and self-esteem. At the very top of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is actualisation. Over the last fifty years or so an increasing number of people have reached the peak of this pyramid and have started searching for meaning and this will continue over the next fifty.Implications? I’d expect an increase in spirituality and a search for experiences that transcend everyday life. So pilgrimages and rites of passage won’t go away either. I’d also expect that whilst some things will still need to be seen to be believed, we’ll see more people believing that things need to be believed to be seen.

Quote of the Week

“You do not merely want to be considered just the best of the best,

you want to be considered the only ones who do what you do.”

– Jerry Garcia

In Praise of Failure

You don’t hear about failure very often. And I’m not just talking about innovations that don’t see the light of day. I’m talking about people too. Why is this? What are we afraid of? After all, it’s not as if it’s unknown. Most companies — indeed, most people — fail more often than they succeed. Life is a series of experiments and a great many, if not most, fail.

Failure is the proverbial elephant-in-the-room. And yet by being scared of failure, we are missing a great opportunity.The point about failure is not that it happens but what we do when it happens. Most people flee or pretend it didn’t happen. Or they find a way to be “economical with the actualite” as a former British Government so elegantly described it.

“We launched too late.” “Consumers weren’t ready for it.” “She was never right for me.”No. You failed. Own up to it. Own it. This is a beginning, not the end. Learn and move on.

The problem, and it’s a big one, is this: Most people believe that success breeds success and they believe that the converse is true too, that failure breeds failure. Says who? There are plenty of people who fail before they succeed, some of whom are serial failures. Indeed, there is rumoured to be a venture capital firm in California that will only invest in you if you’ve gone bankrupt twice.

Take James Dyson, the inventor of the bag-less vacuum cleaner. He built 5,127 prototypes before he found a design that worked. He looked at his failures and learned. He then looked at his next failure and learned some more. Each adaptation led him closer to his goal. As someone once said, there’s magic in the wake of a fiasco. It gives you the opportunity to second guess.

None of this is to be confused with the mantra of most motivational speakers who urge you not to give up. Success is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration they say, and if you just keep on trying, it will eventually happen. And if it doesn’t, you’re just not trying hard enough. This is a big fat lie. Doing the same thing over and over again in the hope that something will change is almost the definition of madness. What you need to do is learn from your failure and try again differently.

All of this brings me to my first point. It is what you do when you fail that counts. Remember Apple’s message pad, the Newton? This was a commercial flop, but the failure was glorious. Indeed, who is to say that the tolerance of failure that is embedded in Apple’s DNA is not one of the reasons why Apple has evolved from a near bankrupt basket case to one of the most valuable and admired companies in history.

Does this mean you abandon your failures? Yes and no. Your idea could be right but your timing, delivery, or execution could be wrong. Who could have guessed that the one-time AIDS wonder drug AZT had been a failed treatment for cancer or that Viagra was a failed heart medication that Pfzer stopped studying in 1992?

As Alberto Alessi once said, anything very new often falls into the realm of the not possible, but you should still sail as close to the edge as you can, because it is only through failure that you will know where the edge really is. The edge is also where real genius resides.

So what I’m interested in promoting are the people whose ideas never get off the ground or rather get somewhere other than where they intended. These are the people who fail on our behalf. The unknown innovators that push things so far to the edge that they fall off. The unlucky or naïve few who open up a new trail — and get scalped — before someone else can see a way through with the wagons. (How’s that for a new historical definition of second-mover advantage?)

There’s a great quote by the writer Douglas Adams that does something like” “I may not have gone where I intended to go, but I think I have ended up where I needed to be.” But an even better quote is by the English sculptor Henry Moore that sums this up pretty well: “The secret of life is to have a task, something you bring everything to, every minute of the day for your whole life. And the most important thing is: It must be something you cannot possibly do.”

So, here’s my idea. Rather than putting up statues to people who did something that was successful, which to be brutally honest is all statues, let’s build monuments to the people who didn’t. Let’s celebrate the lives of people who invented things that didn’t work or tried to do something that was just plain crazy or ahead of its time. A monument to the unknown innovator in pursuit of an impossible dream. The people we watch with perverse envy when we are too scared, too self-conscious, or too constrained to fail ourselves. Because without these wonderful people, there would be no progress or success.

Here are my top tips for failing with greater frequency and style:

• Try to fail frequently, but never make the same mistake twice.

• Set a failure target as part of each employee’s annual review.

• If projects are a failure, kill them quickly and move on.

• Create a failure database as part of knowledge management.

• Keep things in perspective. Something failed. Nobody died.

• Set up annual failure awards. If this gets successful, stop it*

*Stephen Pile’s Book of Heroic Failures spawned the Not Terribly Good Club of Great Britain. Unfortunately, the club received 30,000 membership applications and had to be closed down because it was a failure at being a failure.

Digital Vs. Human in Korean, Russian, Indian & Turkish

Various translations of my book Digital Vs. Human are starting to emerge. I love the Korean cover – almost looks like a film poster.