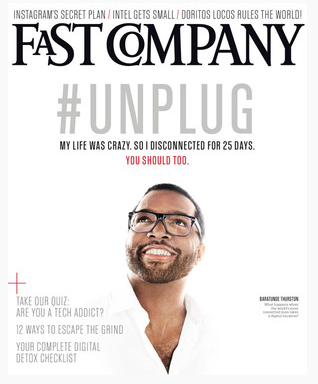

Seems that the world has finally caught up with the idea that we are becoming too connected and that a little disconnection from time to time would be a good thing. Then again, perhaps it’s just July/August and some people just want to be left alone on holiday.

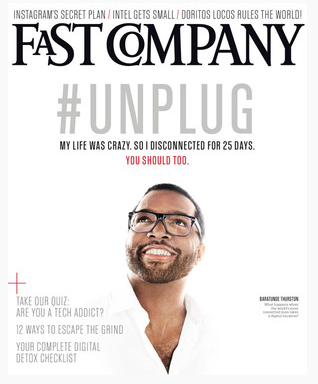

It’s interesting to note that the current issue of Fast Company is all about switching off. So too is the current issue of Stylist magazine. They interviewed me on the phone about this issue a few weeks ago (so not quite as disconnected as they’ll have you believe in the magazine!).

BTW, here’s a tiny taste of what I was saying in my book Future Minds back in 2010.

CONNECTIVITY ADDICTION

A study from the University of California (Irvine) claims that we last, on average, three minutes at work before something interrupts us. Another study from the UK Institute of Psychiatry claims that constant disruption has a greater effect on IQ than smoking marijuana. No wonder, then, that the all-time bestselling reprint from the Harvard Business Review, a management magazine, is an article about time management. But did anyone find the time to actually read it properly?

We have developed a culture of instant digital gratification in which there is always something to do—although, ironically, we never seem to be entirely satisfied with what we end up choosing. Think about the way people jump between songs on an iPod, barely able to listen to a single song, let alone a whole album. No wonder companies such as Motorola use phrases like “micro boredom” as an opportunity for product development.

Horrifyingly, a couple in South Korea recently allowed their small baby daughter to starve to death because they became obsessed with raising an “avatar child” in a virtual world called Prius Online. According to police reports, the pair, both unemployed, left their daughter home alone while they spent 12-hour sessions raising a virtual daughter called Anima from an internet café in a suburb of Seoul.

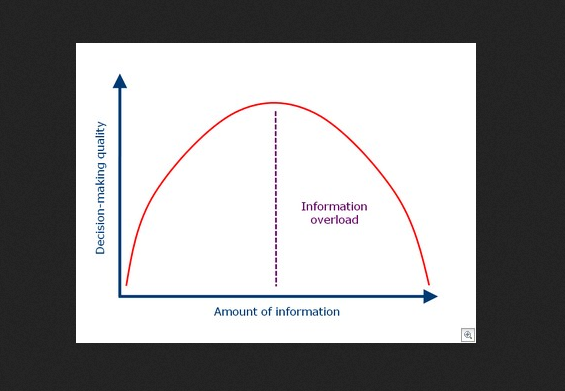

Internet addiction is not yet a globally recognized medical condition, but it is only a matter of time. Already 5–10 per- cent of internet users are “dependent,” according to the Computer Addiction Center at Harvard’s McLean Hospital. This is hardly surprising when you stop to consider what is going on. According to a University of California (San Diego) study, we consumed three times more information in 2008 as we did back in 1960.

Furthermore, according to Clifford Nass, a professor of communications at Stanford University, there is a growing cohort of people for whom the merest hint of new information, or the faintest whiff that something new is going on somewhere else, is irresistible. You can see the effect of connectivity cravings first hand when people rush to switch on their cellphones the second their plane lands, as though whatever information is held inside their phone is so important, or life threatening, that it can’t wait for five or ten minutes until they are inside the air- port terminal. I know. I do it myself.

The thought of leaving home without a cellphone is alarming to most people. So is turning one off at night (many people now don’t) or on holiday. Indeed, dropping out of this hyper-connected world, even for a week, seems like an act of electronic eccentricity or digital defiance.

In one US study, only 3 out of 220 US students were able to turn their cellphones off for 72 hours. Another study, con- ducted by Professor Gayle Porter at Rutgers University, found that 50 percent of BlackBerry users would be “concerned” if they were parted from their digital device and 10 percent would be “devastated.”

It’s more or less the same story with email. Another piece of research, by Tripadvisor.com, found that 28 percent of respondents checked email at least daily when on a long weekend break and 39 percent said they checked email at least once a day when on holiday for a week or more.

A study co-authored by Professor Nada Kakabadse at the University of Nottingham in the UK noted that the day might come when employees will sue employers who insist on 24/7 x 365 connection. Citing the example of the tobacco industry, the researchers noted how the law tends to evolve to “find harm.” So if employers are creating a culture of constant connectedness and immediacy, responsibility for the ensuing societal costs may eventually shift from the individual to the organization. Broken marriage and feral kids? No problem, just sue your employer for the associated long-term costs.

A banker acquaintance of mine once spent a day in a car park above a beach in Cornwall because it was the only spot in which he could make mobile contact with his office. His firm had a big deal on and his virtual presence was required. “Where would I have been without my BlackBerry?” he said to me later. My response was: “On holiday with your family taking a break from work and benefiting from the reflection that distance provides.” He hasn’t spoken to me since we had this conversation, although he does send me emails occasionally. I usually pretend that I’m on a beach and haven’t received them.

It’s happening everywhere. I have a middle-aged female friend (a journalist) who goes to bed with a small electronic device every night. Her husband is fed up and claims it’s ruining their sex life. Her response is that she’s in meetings all day and needs to take a laptop to bed to catch up with her emails. This is a bit extreme, but I know lots of other people who take their cellphones to bed. How long before they’re snuggled up in bed late at night “attending” meetings they missed earlier, having downloaded them onto their iPad or something similar? Talk about having more than two people in a marriage.

Our desire to be constantly connected clearly isn’t limited to work. Twitter is a case in point. In theory, Twitter is a fun way to share information and keep in touch, but I’m starting to wonder whether it’s possible to be too in touch.

I have some friends who are “Twits” and if I wanted to I could find out what they’re doing almost 24/7. One, at least, will be “Eating marmite toast” at 7.08 pm and the other will be “In bed now” at 11.04 pm or “looking forward to the weekend” at 11.34 pm. Do I need to know this?

Why is all of this significant? In A Mind of Its Own, Cordelia Fine makes the point that the brain’s default set- ting is to believe, largely because the brain is lazy and this is the easier, or more economical, position. However, when the brain is especially busy, it takes this to extremes and starts to believe things that it would ordinarily question or distrust. I’m sure you know where I’m going with this but in case you are especially busy—or on Twitter—let me spell it out. Our decision-making abilities are at risk because we are too busy to consider alternatives properly or because our brains trip us up by fast tracking new information. We become unable to exclude what is irrelevant and retain an objective view on our experience, and we start to suffer from what Fredric Jameson, a US cultural and political theorist, calls “culturally induced schizophrenia.”

If we are very busy there is every chance that our brain will not listen to reason and we will end up supporting things that are dangerous or ideas that seek to do us, or others, harm. Fakery, insincerity, and big fat lies all prosper in a world that is too busy or distracted. Put bluntly, if we are all too busy and self-absorbed to notice or challenge things, then evil will win by default. Or, as Milan Kundera put it: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

Crikey. That sounds to me like quite a good reason to unsubscribe from a few email newsletters and turn the cell- phone off once in a while—to become what Hal Crowther terms “blessedly disconnected.”