Talk for the Dubai government at Judge Business School at Cambridge University recently. https://www.instagram.com/mbrinnovation/?hl=en

Category Archives: Innovation

Celebrate Failure!

Thought for Thursday

“And what was the true object of this superstitious stuff? A final clue came from “Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention” (1996), in which Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi acknowledges that, far from being an act of individual inspiration, what we call creativity is simply an expression of professional consensus. Using Vincent van Gogh as an example, the author declares that the artist’s “creativity came into being when a sufficient number of art experts felt that his paintings had something important to contribute to the domain of art.” Innovation, that is, exists only when the correctly credentialed hivemind agrees that it does. And “without such a response,” the author continues, “van Gogh would have remained what he was, a disturbed man who painted strange canvases.” What determines “creativity,” in other words, is the very faction it’s supposedly rebelling against: established expertise.”

Taken from Salon, ‘TED talks are lying to you’ by Thomas Frank

(Article originally published in Harper’s)

Why Companies Die

Why is it that the average lifespan of an S&P 500 company in the US has fallen from 67 years in the 1920s to just 15 years today? And why might 75% of firms in the S&P 500 now be gone or going by the year 2027 or thereabouts?

These figures come from a study by Richard Foster at the Yale School of Management and echo another from the Santa Fe Institute that found that publically quoted firms die at similar rates regardless of age or industry sector. In this second study the average lifespan of American companies was cited at just 10 years. The reason given for most of these companies dying or disappearing is a merger or acquisition.* A third US study** of S&P companies reports an average company age of 61 in 1958, 25 in 1980 and around 18 today, but the trend toward shorter lives remains regardless of which study you read.

In the UK it’s a similar story. Of the 100 companies in the FTSE 100 in 1984, only 24 were still breathing in 2012, although average corporate lifespans in the UK were somewhat longer. However, with start-ups it’s back to bleak, with almost 50% of SMEs failing to celebrate their 5th birthday. The reasons UK start-ups fail are said to include cash flow issues, a lack of bank lending, too much red tape, high business rates and competition.

With larger enterprises in the UK and elsewhere the situation can be somewhat different. The main reason that big companies die – beyond being consumed by larger or more aggressive companies – is that they fail to anticipate or react to new technology, new customer demands or competitors with new business models, products and services, all of which are often linked and can cause considerable disruption and disturbance.

This is Darwinian evolution applied to capitalism and the only solution is to keep your eyes and ears wide open for predators and to continually evolve what you do through a process of constant adaption and occasionally accelerated mutation.

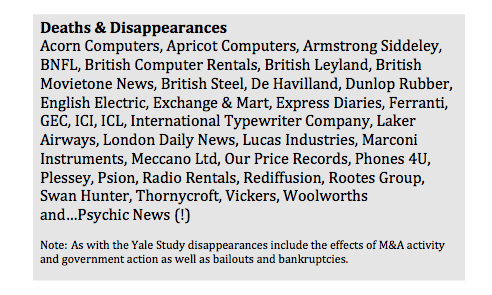

The list of corporate casualties is certainly long. Most people are aware of how things developed at Kodak, but the list of companies killed off or seriously injured by new technologies, new competitors or new customer behaviours includes a roll call of previously proud British names including Ferranti, Psion, Acorn Computers, De Havilland, British Leyland, British Steel, ICI, Marconi, Swan Hunter, Armstrong Siddeley, GEC and ICL.

Interestingly, in each case the writing was on the wall long before many of these companies went bankrupt or were taken over, but if there’s one thing that you can rely on with big companies it’s that, like super-tankers, they can take a long time to change direction and the view from the bridge is often partially obscured or heavily contested.

Nothing recedes like Success

Putting to one side new technologies, new competition and new customer demands, a key point is geriatric corporate cultures. Bill Gates once said that “success is a lousy teacher, it seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.” In other words, nothing recedes quite like success and large companies can become delusional about their fitness, their intellect or the speed and energy with which new ideas and inventions can move.

If arrogance is one silent killer, another is that as companies grow and become bigger management can become distanced from both insight and innovation. Peter Drucker made this point decades ago, although he used the word entrepreneurship. Managing and innovating are different dimensions of the same task, but most large companies regard them as separate to the point of putting them in different departments or locations. As the urgency to stay alive financially evaporates the focus shifts away from urgent opportunities and threats to lethargic internal issues and a kind of corporate immune system develops whereby new ideas tend to be rejected by the corporate body the minute they form.

If you drop down the organisation chart to departments such as customer complaints this isn’t always the case. People working in customer relations, IT, sales or even accounts can be extremely close to customers, and hence to the inception of new ideas, but senior management often writes off these departments as cost centres rather than hotbeds of insight and innovation. With R&D it’s often much the same story with scientists and engineers being regarded as grey suited bureaucrats offering up ponderous improvements rather than white-coated warriors fighting for discoveries that could transform the company.

The culture of organisations contributes to failure in other ways too. The dominant culture of most very large companies is highly conservative and quite rightly so. Publically quoted firms primarily exist to provide a regular return to shareholders and to keep workers in regular employment. But to do both these things they must also deliver constantly evolving products that create value for customers.

This is like a tightrope that’s not only swaying in the wind, but is being constantly moved and adjusted at one end while you’re still walking along it. Interestingly, Mark Vergano, an executive VP at Du Pont once made a similar point with regard to R&D saying that: “Research and development is always a delicate balance between maintaining a long-term view and remaining sensitive to short-term financial objectives.”

To sum up, if companies wish to remain healthy and grow old they need to do two things. Firstly, they need to remain young at heart. They need to remain mentally agile, constantly learn new things and question their own identity and reason for being.

This means repeatedly asking what business they’re really in and how best they can serve both current and future customers using current and future technologies, channels and business models.

Secondly, companies must look at innovation from a whole business perspective and make innovation truly cross-functional. If innovation exists purely at a departmental, product or service level it’s unlikely to proceed beyond incremental refinement. Continuous improvement is essential, but it’s merely a ticket to stay in the game. To win the game companies must consider more radical developments including the ground up reinvention of everything they do and also link innovation to strategy.

Three quick ways to extend the lifespan of your company:

1. Constantly look out for and test new ideas that could breathe new life into your company or fatally wound it if applied by a competitor.

2. In a similar vein don’t simply keep an eye on what your closest competitors are doing, also study what small start-ups outside your immediate market or geography are doing too. Are they doing anything unusual? Are they doing anything that doesn’t immediately make sense? If so dig into why.

3. Keep a close eye on what your youngest customers and employees are doing. What are they doing that you aren’t? Could such behaviour be an early warning signal of change?

Footnotes.

* A merger or acquisition isn’t necessarily a business failure, but can nevertheless be a sign of weakness or long-term illness.

**Innosight study (US).

If you’re wondering, the world’s oldest limited liability corporation is Enso Stora, a Finnish paper and pulp manufacturer that started out as a mining company in 1288.

Why Companies Die

Why is it that the average lifespan of an S&P 500 company in the US has fallen from 67 years in the 1920s to just 15 years today? And why might 75% of firms in the S&P 500 now be gone or going by the year 2027 or thereabouts?

These figures come from a study by Richard Foster at the Yale School of Management and echo another from the Santa Fe Institute that found that public companies die at similar rates regardless of age or industry sector. In this second study the average lifespan of American companies was cited at just 10 years. The reason given for most of these companies dying or disappearing is a merger or acquisition.* A third US study** of S&P companies reports an average company age of 61 in 1958, 25 in 1980 and around 18 today, but the trend toward shorter lives remains regardless of which study you read.

In the UK it’s a similar story. Of the 100 companies in the FTSE 100 in 1984, only 24 were still breathing in 2012, although average corporate lifespans in the UK were somewhat longer. However, with start-ups it’s back to bleak, with almost 50% of SMEs failing to celebrate their 5th birthday. The reasons UK start-ups fail are said to include cash flow issues, a lack of bank lending, too much red tape, high business rates and competition.

With larger enterprises in the UK and elsewhere the situation can be somewhat different. The main reason that big companies die – beyond being consumed by larger or more aggressive companies – is that they fail to anticipate or react to new technology, new customer demands or new competition, all of which can be linked to each other causing considerable disruption.

This is Darwinian evolution applied to capitalism and the only solution is to keep your eyes and ears wide open for predators and to continually evolve what you do through a process of constant adaption and occasionally accelerated mutation.

The list of corporate casualties is certainly long. Most people are aware of how things developed at Kodak, but the list of companies killed off or seriously injured by new technologies, new competitors or new customer behaviours includes a roll call of previously proud British names including Ferranti, Psion, Acorn Computers, De Havilland, Marconi, Swan Hunter, Armstrong Siddeley, GEC and ICL.

Interestingly, in most cases the writing was on the wall long before many of these companies went bankrupt, but if there’s one thing that you can rely on with big companies it’s that, like super-tankers, they can take a long time to change direction and the view from the bridge is often obscured or contested.

Putting to one side new technologies, new competition and new customer demands, a key point is geriatric corporate cultures. Bill Gates once said that “success is a lousy teacher, it seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.” In other words, nothing recedes quite like success and large companies can become delusional about their fitness, their intellect or the speed with which young ideas and inventions can move.

If arrogance is one silent killer, another is that as companies grow management can become distanced from both insight and innovation. Peter Drucker made this point decades ago, although he used the word entrepreneurship. Managing and innovating are different dimensions of the same task, but most large companies regard them as separate to the point of putting them in different departments or locations. As the urgency to stay alive financially evaporates the focus shifts away from urgent opportunities and threats to lethargic internal issues and a kind of corporate immune system develops whereby new ideas tend to be rejected by the corporate body the minute they form.

If you drop down the organisation chart to departments such as customer complaints this isn’t always the case. People working in customer relations, IT, sales or even accounts can be extremely close to customers, and hence to the inception of new ideas, but senior management often writes off these departments as cost centres rather than hotbeds of insight and innovation. With R&D it’s often much the same story with scientists and engineers being regarded as grey suited bureaucrats offering up ponderous improvements rather than white-coated warriors fighting for discoveries that could transform the company.

The culture of organisations contributes to failure in other ways too. The dominant culture of most very large companies is highly conservative and quite rightly so. Publically quoted firms primarily exist to provide a regular return to shareholders and to keep workers in regular employment. But to do both these things they must also deliver constantly evolving products that create value for customers.

This is like a tightrope that’s not only swaying in the wind, but is being constantly moved and adjusted at one end while you’re still walking along it. Interestingly, Mark Vergano, an executive VP at Du Pont once made a similar point with regard to R&D saying that: “Research and development is always a delicate balance between maintaining a long-term view and remaining sensitive to short-term financial objectives.”

To sum up, if companies wish to remain healthy and grow old they need to do two things. Firstly, they need to remain young at heart. They need to remain mentally agile, constantly learn new things and question their own identity. This means repeatedly asking what business they’re really in and how best they can serve both current and future customers using current and future technologies, channels and business models.

Secondly, companies must look at innovation from a whole business perspective and make innovation truly cross-functional. If innovation exists purely at a departmental, product or service level it’s unlikely to proceed beyond incremental refinement. Continuous improvement is essential, but it’s merely a ticket to stay in the game. To win the game companies must consider more radical developments including the ground up reinvention of everything they do.

——

* A merger or acquisition isn’t necessarily a business failure, but it is often a sign of weakness or long-term illness.

**Innosight study (US).

If you’re wondering, the world’s oldest limited liability corporation is Enso Stora, a Finnish paper and pulp manufacturer that started out as a mining company in 1288.

The Future of You

Something light for the new year.

1) New Year Resolution grid from Ian Fitzpatrick (via Artefact Cards).

More about here

2) Love, work & money (i.e. career planning) by Remo Giuffre.

More about here

Why do some things get invented while others don’t?

Looking back over a few decades of dealing with innovators, large and small, there appear to be a few reasons why some ideas – and people – make it while others don’t. This is not an exhaustive list. Neither does it take into account factors such as finding a large enough problem, financial issues, regulation or a host of other things innovators need to worry about. This is merely a subjective summary of why some people seem to succeed and others don’t, especially when it comes to making critical decisions about new ideas, products, services and strategies.

One reason that many people fail to get their ideas off the ground is that they sink too much of themselves into a project. They continue to back fixed strategies and designs well past the point of no return in a futile quest to get their sunken time and especially their hard earned cash back.

In contrast, smart innovators practice fast failure. When projects reach a point of diminishing returns they get out fast to avoid losing even more time and money – and start again in a totally different way. This trait of not letting go or adapting is especially prevalent with individual inventors. These individuals will not adapt their idea, or change their vision, even when doing so might attract investors or make the final route to market so much easier.

Sometimes dogged determination and persistence do pay off. Indeed, history is littered with examples of might be called ‘endurance invention’, where heroic individuals have struggled, often for years (even decades), before their ideas finally become accepted. James Dyson, the inventor of the bag-less vacuum cleaner, Trevor Baylis, the inventor of the windup radio, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison and even Colonel Sanders are well-known examples.

But these stories are somewhat misleading. More often than not, a desire for absolute control and total secrecy over and above flexibility, pragmatism and collaboration kills good ideas stone dead.

At the extreme, individual inventors will not share their ideas with anyone because they fear that their idea will be stolen or misused. This does indeed happen. But no non-disclosure agreement will prevent this unless you are prepared to spend staggering sums of money on lawyers. This is also a very negative mindset.

Yes, there are people out there that will rob you blind, but most people will not. Most people want to help you. Moreover, you cannot do everything yourself. At some point you will have to let go and let others craft and polish your idea, especially if your aim is scale or making a dent in the universe.

What else goes wrong? In my experience, a second reason that good ideas go bad is access to too much time and money. With small firms austerity and necessity can be the father and mother of invention. If you don’t have much money you are forced to think. But with large organizations, and indeed institutions, too much time and too much money can be fatal.

Large companies are generally risk-averse perfectionists. They are inherently conservative (often rightly so), but the downside is they often focus too much on their legacy idea or business model and move at a snail’s pace when it comes to anything new. They move so slowly, in fact, that many a market opportunity will have expired by the time a ‘perfect’ idea is launched. Most large firms inhabit this terrain, which is why they are regularly outmanoeuvred by smaller, less constrained, start-ups with a more flexible view of the future.

Linked to this thought is the idea that people behave very differently with ideas they own compared to ideas they don’t. If overcommitted individual inventors not letting go is one problem, people in large companies not having any skin whatsoever in the innovation game is another. After all, why fight to the death for an idea if there’s no personal benefit attached, or if there is a chance that support or investment will be withdrawn once a senior decision maker or supporter moves upward or outward.

A third reason that good ideas go nowhere is that our brains are designed to deceive. Essentially, all information and experience gets a ‘tag’ and is stored away deep inside our heads. However, such information and experience do not sit quietly on the sidelines, waiting patiently to be called up when they will be most useful. Ideas are connected to other stored ideas and we use them to make decisions, judgements and to cross-fertilise our thinking.

But occasionally these connections let us down. Sometimes memories attach themselves to information that results in false pattern recognition or understanding. We think that we understand a problem or a solution based on previous experience, when in fact we do not. An example might be Segway. This was a technically brilliant idea, but I suspect that Dean Kamen failed to see what was hidden in plain sight. Namely that the Segway was dangerous on the freeway and dangerous on the sidewalk and that people don’t like talking to people that are higher off the ground than they are.

Such misinformation and alignment links closely with confirmation bias, which is a fourth reason that things can go from good to bad very quickly. In short, our conscious minds seek out information that will support or confirm our existing beliefs or hypotheses, while our subconscious blocks out any information that might argue against these thoughts. This is a reason why future predictions tend to heavily bias toward the present order.

A fifth and final reason for failure is egocentric bias. The issue here is that we usually think that we are right. This isn’t generally a problem with sole inventors or companies with just one employee, but with teams – or marriages – you can imagine the consequences. Everyone in a team has an opinion about what should be done and spends most of their time ensuring that any contrasting or dissenting opinion in silenced.

Can anything else go wrong? You bet. The list is almost endless to the point where one wonders how anything new gets invented at all. So I will end with just a few ways that you can stop good ideas going bad.

1. Be open-minded and pragmatic. Being broadly right is always better than being precisely wrong – or as the Nike slogan says: “Just do it”

2. Create a sense of urgency. If things start to go wrong, or get bogged down, apply the principle of half the time and half the money. If this doesn’t work halve things again. And if this doesn’t work try giving someone absolute power, one direct report to the CEO and no budget.

3. As Grouch Marx once said” A four-year-old child could understand this. Quick, get me a four-year-old child”. So find a (slightly older) child and explain your problem or solution. Do they get it? If not you’ve not explained it properly and/or you’ve made everything too complicated.

4. Similarly, seek out the opinions of disinterested outsiders. If you can’t find a child ask your mum or a random stranger. What do they think? What would they do?

5. Finally, remember that it is always better to fail whilst daring greatly. Ones place in history should never be with those timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat. (Or put another way: it’s usually easier to beg for forgiveness than seek legal permission).

Innovation Best Practice

Just been reading The Department of Mad Scientists by Michael Belfiore, which is about the work of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the US. If you haven’t heard of DARPA, and most people outside the US haven’t, these are the folks that more or less invented things like the internet (originally called ARPANET) and GPS.

Not as interesting as I thought it would be, although there was a little gem hidden inside. One of the secrets to DARPAs success as an innovator is that as well as minimal bureaucracy and low overheads the organization has strict term limits for its managers. This means that people have a maximum of 4-5 years to make an impact. This reminds me slightly of an ex-CEO of Unilever in the UK who would halve the budget and bring forward the deadline on innovation projects that had stalled. Necessity may be the mother of invention, but adversity often appears to be the father.

Thinking outside the box

This is fun. In a study of the physical embodiment of metaphors conducted by Angela K.-y. Leung of Singapore Management University, people who literally sat “outside the box”—a box made of cardboard and plastic pipe – produced 32% better answers to a test than people sitting inside the box.

Source: HBR/ Embodied Metaphors and Creative “Acts”

Hot heads Vs. Getting Cold Feet

So I’m sitting in my home office freezing my feet off. It was 45 degrees C in Sydney a few days ago, so the image is for anyone down-under wanting to cool off. This has made my mind wander. I mentioned in a post a few days ago that a study had said that being warm increases creativity. So if you took a list of Nobel Prizes, or patents, could you draw any kind of linkage with average country temperature and original thinking? Or what about revolutions? Is there a link between propensity to revolt and average temperature? You might think this is nuts, but there’s a proven (but complex) linkage between crime and temperature.