Here is the full text of my speech to the RSA today. A podcast will be available within a few days and a Youtube video will be up in a couple of weeks.

—

There was a report in a newspaper recently about a mother whose six-year-old had asked her whether he should put a slice of bread in the toaster “landscape or portrait?” I mentioned this to my ten-year-old and he said “He should have Googled it.”

So why am I here and, more interestingly, why are you?

The answer to the first question is simple. I’m trying to get people interested in my new book, Future Minds, and I’m not on Facebook or Twitter. As to why you’re here that’s a far more interesting question. After all, you could have watched this on Youtube.

I’d like to suggest an answer to the second question at the end of this, but before I do that I should return to the book. What’s it about and why did I write it?

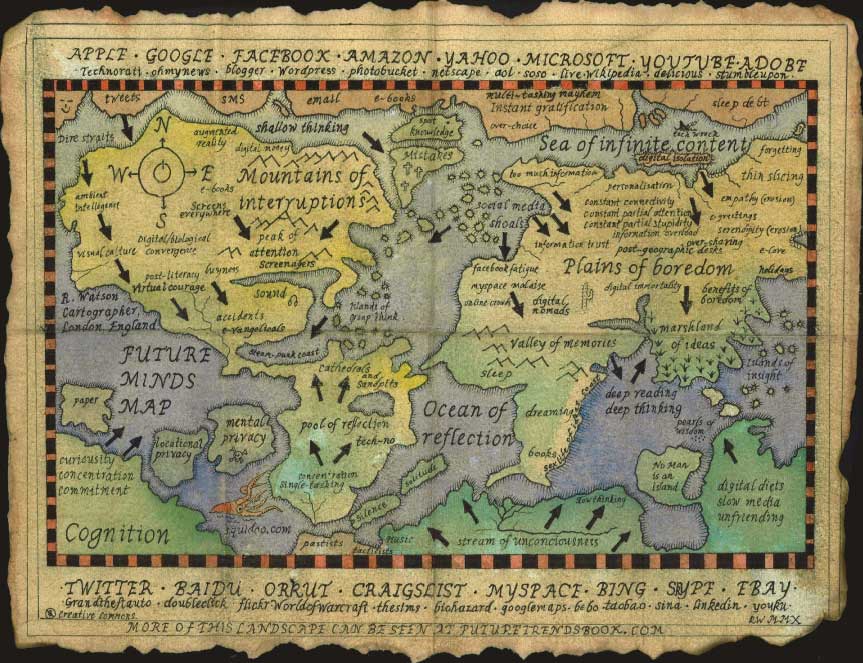

The book is about our relationship with technology, specifically digital technology and screen culture. It’s about how 4 billion mobile phones, 2 billion PCs, 500 million Facebook accounts and a Googlezillion internet searches, texts, and Tweets could, if we’re not careful, lead to the death of deep thinking.

At least that’s what the book ended up being about.

The reason I wrote the book is that I had an idea. An idea that occurred to me one morning when I was slowly sipping coffee, staring into space from the rooftop of a hotel overlooking Sydney harbour. But then I thought to myself – would I be having this thought if I were on the phone, looking at a computer screen, in a basement in London? I thought then – and I still think now – that the answer is no. Modern life is changing how we think, but perhaps the clarity to see this only comes with a certain distance or detachment.

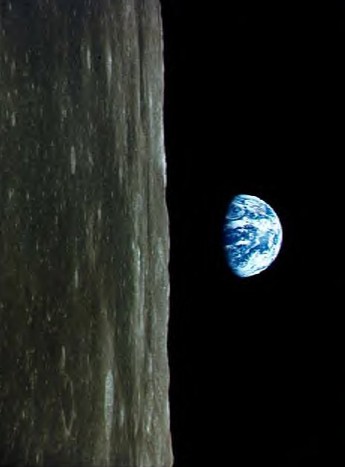

The Overview Effect is the state of heightened consciousness that astronauts experience when they look back at the Earth from a great distance away. It’s what William Anders, Frank Borman and James Lovell, the crew of Apollo 8, experienced on Christmas Eve 1968, when they saw something nobody had ever seen before.

It was an Earthrise. A fragile blue planet rising optimistically above an inhospitable lunar landscape. Recognising that this was significant, Anders grabbed a camera and took some photographs, which effectively started the environmental movement back on Earth in the early 1970s.

This story proves, to me at least, that external stimuli influence our thinking and that attitudes and behaviours that we often assume are fixed are constantly being influenced by the objects and environments we come into contact with.

My original idea was to write a book about how physical spaces influence thinking. A book about architecture and office design essentially.However, my publisher pointed out that such a book would probably sell about 3 copies, so I broadened the remit to include virtual spaces, digital devices and eventually screen culture. It thus became a book about the future of thinking with a set of social and technological trends as the unifying force.

Ultimately, though, it’s about something else. It’s about our addiction to digital technology and the way this is changing our relationships with each other.

The book is split into three parts.

The first part is about how attitudes and behaviours are changing. It looks at teens and pre-teens and considers, amongst other things, connectivity addiction, the multitasking myth, risk-averse parenting, electronic games, the fate of physical books and whether IQ tests could be making kids stupid.

The second part of the book is about why this matters. This section looks at how our minds are different to machines, considers where ideas come from and contains a rant about paperless offices and a gentle plea for organised chaos.

The third and final section is then about what we, as individuals and institutions, can do about a world choked with too much information and too much distraction and offers some practical suggestions.

I’d like to look briefly at each of the three sections.

1. How are attitudes and behaviours (and brains) changing?

We are constantly connected nowadays. This is largely due to digital technology. A decade ago there were fewer than 500 million mobile phone subscribers worldwide. Now there are 4.6 Billion. In the UK 50% of children aged between 5 and 9 now own a mobile phone.

One consequence of all this connectivity is that we are continually distracted. As a result we never get a chance to really be by ourselves, which means we never get a chance to really know ourselves. We never get the opportunity to sit quietly and think deeply about who we are and where we are going.

Ironically, this connectivity also means that we tend to be alone even when we are together. You can see this when couples go out to dinner and spend most of their time texting – or when kids get together for play-dates and end up sitting next to each other on separate gaming consoles for hours on end. This is what I call Digital Isolation.

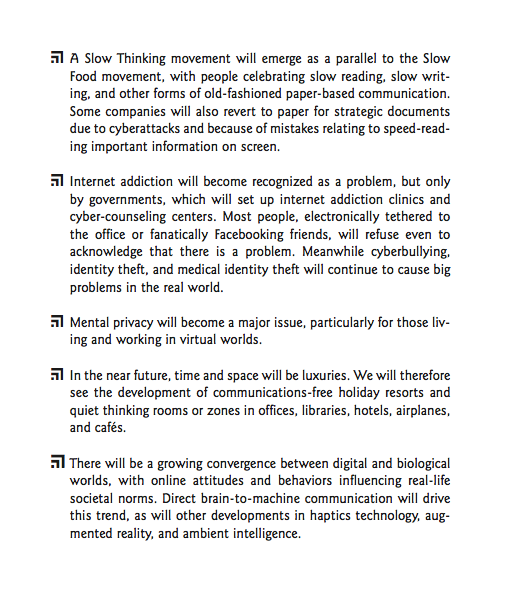

What worries me most though is the quality of our thinking, which I believe is becoming shallow, narrow, cursory, hurried, fractured and thin. This is problematic because originality largely depends on thinking that is deep. Serious creativity, whether it be in business, science or the arts, is largely dependent on thinking that is calm, concentrated, focussed, attentive and above all reflective.

Another implication of constant connectivity and distraction is that it can lead to mistakes, some of which can be fatal. This is what I call Constant Partial Stupidity.

We tend not to fully concentrate on one thing nowadays. Instead, we continually scan the digital environment for new information. And we start to believe that we can do more than one thing at once. But we end up getting distracted again and forget about what we are supposed to be doing. According to a 2009 US study, multi-tasking is becoming the normal state. However, the same study found that the people that multi-task the most are in fact the worst at it.

Heavy multi-taskers are poor at analysis and forward planning. They also lose the ability to ignore irrelevant data. They are suckers for distraction and become bored when they are not constantly and instantly stimulated.

Now it’s quite true that you can always turn the technology off, but most of us don’t because there is cultural pressure to be constantly available and to instantly respond. For example, I know a 13-year old girl that’s on Facebook. She would rather not be but all her friends are and the pressure to remain on is immense.

As for mistakes these can be serious. I don’t know whether you’ll remember Mr de Silva but this was the man that famously used his laptop to get instructions on how to avoid a traffic jam on the M6 motorway. Unfortunately, he was driving a lorry at the time and smashed into a line of cars killing six people.

He is not alone in outsourcing his thinking to a machine. For example, if you can Google any piece of information more or less instantly why bother learning anything? If a Sat Nav can always tell you where you are why worry about situational awareness or bother to learn how to read a map?

Twenty years ago Mr de Silva would have planned ahead. He would have plotted out his journey and would have known roughly where he was due to an elementary knowledge of geography. Nowadays we make everything up on the run and delegate geography to a blind trust in technology.

It seems to me that we need context as well as text. We need to understand principles before we move on to applications. We need breadth and depth not superficial facts. Unless we know how things relate to one another we will just have information. For knowledge we need to understand connections. For wisdom we need to understand consequences.

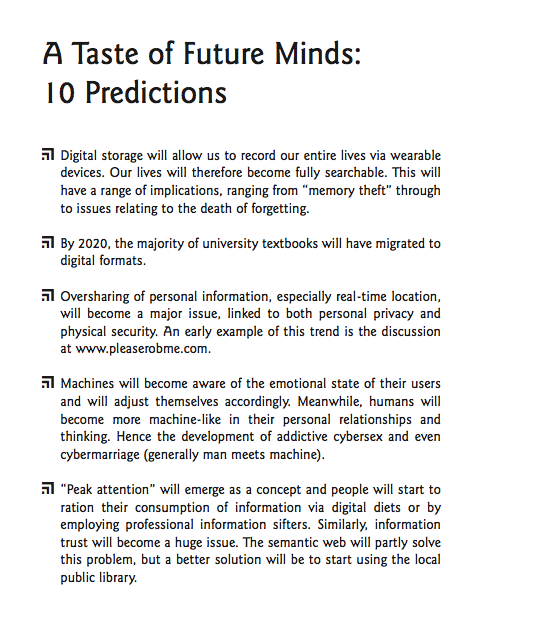

Second, if everyone is using the same sources what of originality? You might think I’m exaggerating about this but I’m not. Far from creating an intellectual paradise, digitalisation appears to be narrowing our thinking. For example, 99% of Google searches never proceed beyond page 1 of results and academic papers are now citing fewer studies not more.

Third, what if one day the technology doesn’t work? What then? We assume, for instance, that the internet will always work. But what if it doesn’t. What if one day the volume of data becomes so great that it becomes blocked? What if energy shortages disrupt access? What if cyber-attacks become such a problem that things of importance are moved offline? What then?

How many individual or institutions have a plan in case mobiles, email, Sat Nav, Google or the entire internet become unusable?

Part 2

Why does any of this matter? Who cares if our brains are changing? We’ve always invented new things. We’ve always worried about new things and we’ve always moaned about younger generations. Surely most of what I’m saying is conjecture mashed up with middle-aged technology angst?

I think the answer to this is that it’s a little different this time. These things are becoming ubiquitous. They are becoming addictive. They are becoming prescribed.

At the moment we have a choice. We can choose paper over pixels. We can choose to talk to a human being rather than a customer service avatar. But what if one day there is no choice. What if all books become e-books? What if all doctors and teachers are replaced by screens or machines? Perhaps we will start to see technology as instructor, which is not that far from viewing technology as master.

This probably sounds fanciful. But it’s all happening already. Governments and businesses alike are moving everything they can online for the sake of cost or convenience. But I am concerned that while the quantity of communications is increasing exponentially, the quality of our communications may be going backwards. This is damaging our thinking and our relationships. Ideas, for example, are inherently social. They need physical interactions if they are to flourish.

Secondly, and more importantly, people need people too. It seems that one by-product of the digital age is that our relationships are becoming more superficial. Thanks to text messages, e-greetings and social networks we know more people but we know them less well. We have replaced intimacy with familiarity.

It is interesting to note that 10 years ago 1 in 10 Americans said they had nobody to confide in. 10 years on and this figure has jumped to 1 in 4. There are over 300,000 applications for the iPhone but apparently not a single app for loneliness.

I’m sure I will be accused of exaggerating this point but it seems to me that empathy and tolerance of others could be two if the casualties of instant digital culture. If we are constantly looking down, in iPod oblivion as it were, we are less aware of others, some of whom may need our help.

Equally, if we are able to personalise our experience of reality via RSS feeds, Google alerts and friendship requests, it is less likely that we will be confronted with ideas or people that challenge the way we think.

Part 3

The internet is a wonderful invention. I couldn’t do much of what I do today without it. Moreover, I am not declaring war on digital devices. Many of them are extremely useful. Neither am I saying that Google is evil or that Apple is rotten. They are not. I’m just arguing for some level of analogue/digital balance, much in the same way that people argue for work/life balance.

I’m saying that we should think further ahead and question some of our assumptions. Also that technology should be used in combination with human judgement not as a replacement. That we use technology to enhance relationships not to negate them

So what can we do?

The first thing we need to do is think. We need to think about the relative merits of different analogue and digital technologies and pick the very best tools for the job. For example, evidence is emerging that pixels are quite different to paper. When we use screens our minds are set on seek and acquire. This is great for the fast accumulation or distribution of facts.

But with paper it’s different. Our minds are more relaxed, we tend to see context. Our thinking is more curious and questioning.

For example, there’s evidence that people are more reckless with money when it’s digital. It’s as though it belongs to someone else and we spend it impulsively. It’s the same, in my experience, with digital statements and bills. We see them, we scan them with our eyes and we forget them. Paper bills and statements, in contrast, seem to have more weight. We take them more seriously and we are on the look out for things that don’t add up.

There are ten suggestions in the book about how to get find the right balance.

Here are three of them.

First, we should restrict the flow of information. In the US, people consumed 300% more information in 2008 than they did in 1960, so one could argue that it is now attention, not information that is power nowadays.

We should learn how to control the flow of information. We should learn that not all information is useful or trustworthy. And we should remember that, despite the digital revolution, the medium still influences the message. Let me give you an example.

When I was writing the book it occurred to me that I needed some more information about where and when people did their best thinking (“best thinking” being deepest, or most useful etc). I decided I needed 1,000 responses to the question. But then it hit me. If I wanted 1,000 responses I’d need to mail about 50,000 to 100,000 people.

But then I had an idea (in the bath as it happens). If people are busy and don’t know me, asking them to stop and think for a few minutes is a lot to ask. But what if my interruption was unusual? What if, as well as emails and phone calls. I sent typed and handwritten letters?

It worked. I got close to my target of 1,000 responses and got replies from, amongst others, Howard Gardner, Susan Greenfield, James Dyson and Nick Mason from Pink Floyd. I even got an indirect response from the Prince of Wales.

What does this prove? I think it shows that that scarcity still creates value and that if something is easy you should resist it. To paraphrase Jack White, from The White Stripes “Convenience is the disease that you have to fight in any creative field.”

The Second thing you can do is disconnect from time to time. Our brains need to relax. If they don’t they can’t function properly. Without rest our memories are not properly stabilised. Moreover, a lack of sleep can inhibit the formation of new brain cells and can lead to depression and hostility.

So switch your mobile off after 6.30pm each night. It’s interesting to me that we try to set boundaries around screen use for our kids, yet we do not restrict our own usage. So resist the urge to take your BlackBerry on holiday. Don’t answer texts in restaurants and don’t send emails when you are spending time with your kids.

This is important, especially if you have small kids. Much of the concern surrounding the use of mobiles, Facebook and Twitter has been focussed on teens – but adults are a major part of the story.

According to Sherry Turkle at MIT, parental use of digital technology is making kids feel hurt. I’ve seen this myself. Last year I attended a school assembly for Fathers Day. There were about 100 kids aged 5-8 and about 50 dads. About half the dads spent the entire time on BlackBerrys. They were connected but not with their kids.

You can see mums doing similar things. When I was growing up prams faced inwards towards the parent. Mobile phones didn’t exist and there was little choice but for the parent to engage with the child. Next time you see a mother (or father) pushing a pram, look at which way the pram is facing and watch what the parent is doing. Then consider what this lack of engagement might be doing to the child’s development.

Most of all, create the time and space to think. When, for instance, was the last time that you told someone that you were going off “to do a bit of thinking.”

Go for a walk. Build something with your hands. Do something that is superficially mundane, that allows your mind to wander. Allow yourself to become bored once in a while too because boredom is a catalyst for creation.Or, instead of having solitary sandwiches at your desk go out for a lunch with some of your colleagues. You could even invite Dionysus along.

Third, Go to places where ideas can find you. As I mentioned, my research asked people where and when they did their best thinking. So what did people say?

Here’s the top ten in order:

1. When I’m alone

2. Last thing at night or in bed

3. In the shower

4. First thing in the morning

5. In the car

6. Reading a book, newspaper or magazine

7. In the bath

8. Outside

9. Anywhere

10. Running

Interestingly, not a single person mentioned digital technology. Nobody said, “On the phone”, “On Facebook”, “Twitter” or “Google”. Technology, it seems, is good for spreading and developing ideas, but not much use for hatching them.

What I also found fascinating was that only one person said in the office, and they said very early in the morning – in other words, when the building wasn’t really functioning as an office at all.

Why don’t people have good ideas at work? The main reason is that they’re too busy. You need to stop thinking and loose your mind before you can have a good idea.

Did any of the answers I received from people about their thinking spaces have anything in common? I think they did. Scale seems to be important. You need to feel small. That’s probably why so many people mentioned beaches, mountains and churches. In such situations our minds seem to expand to fill the available space. Seeing a distant horizon also appears to help in that our thinking is projected forward.

Movement (especially planes, trains and automobiles) is good, as are environments that are slightly restricted or beyond our control (i.e. a long-haul plane trip where you can’t go anywhere). I imagine prisons are quite good too.

I’ve run out of time so I’ll leave you with one final thought. Technology is not destiny. The human brain is, as far as we know, the most complex structure in the universe. But it has one very simple feature. It is not fixed. It is malleable. It is impressionable to the point where it records every single thing that happens to it.

You might think that text messages, internet searches and Sat Nav’s don’t affect you but you’d be wrong. They already have. The question is therefore not whether they will influence your thinking but how. The real question, though, is whether or not we have the time to change things if we want some things to stay the same.

Now I said at the beginning that I was curious about why you were here. Of course, the answer could be that you aren’t on Facebook or Twitter either. But I don’t think that’s it. I think the reason you are here is because you share similar concerns.

A concern that the global is starting to destabilise the local.

A concern that the virtual is starting to weaken the physical.

A concern that the cold logic of computers is taking the warmth out of human relationships and that digital culture is not a wholly positive development.

Most of all though, I suspect you are here because everyone else is, which is much the same as saying that despite the dexterity of our digital devices, machines are currently incapable of providing three things that people value very highly, namely curiosity, questions and physical connection.

Thank you very much.