Street Philosophy

This needs wider attention. From the artficial stupidity blog.

New Public Management and Education

Setting targets in the NHS which ignore the fundamental context in which hospitals and administrators work – the care of health – has catastrophic, lethal consequences. Setting targets for the Police to make them more accountable and rewarding those who hit the targets set and punishing those who fail, inevitably results in people playing the system until no one really knows what the true crime figures are.

In British education today we have a system that combines the worst of both these worlds. Politicians and education policy makers do not ask and cannot say what education is for, and with their rewards and punishments they encourage a gaming of the system which is arguably even more corrupting than the gaming that happens in policing. Worse, credible evidence suggests that this system is damaging the very children’s education it claims to improve. Report after report exposes this and nothing is done.

The background

It has been nearly 45 years since any serving cabinet minister, let alone Prime Minister, has asked what our children’s education is for.

The last was Jim Callaghan, then prime minister, who in his 1976 speech at Ruskin College Oxford began a debate on education in Britain that lasted for years. He suggested that:

“The goals of our education … are to equip children to the best of their ability for a lively, constructive, place in society, and also to fit them to do a job of work. Not one or the other but both.” At the time of the speech, the condition of education – at least in state schools – was monitored by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate (the HMIs). They inspected schools nationally and the Chief Inspector consolidated and summarised the information they gathered for the Secretary of State for Education. In parallel to HMIs, Local Education Authorities sent teams in to schools in their area, inspecting and more especially, advising.

HMI’s were careful to differentiate particular needs of schools during their inspections; schools understood that inspections were an opportunity to have a dialogue aimed at raising standards, and ministers accepted – even when they did not enjoy – the strict independence of HMIs from the whims and vagaries of governments. The result was that HMIs were generally respected by schools, teachers and parents.

That is not to say it was a perfect system. It suffered from inconsistent standards across the country and many people were concerned about the independence of inspectors, of local chief education officers and councillors.

Up until the 1970s in general education, as somewhat earlier in medical education, people largely accepted that the experts – teachers, Local Education Authorities and civil servants – knew best and were working together for society and for the good of children. But as had happened in medical education, and as was happening in the police, the political climate was changing and the old assumptions and authorities were being questioned, not just by the young, but by the new breed of politicians as well.

Professor Terence Kealey, vice-chancellor of the University of Buckingham, and a former adviser to Baroness Thatcher claimed in 1980 that it was her reforms that led to more transparency and accountability within the sector, while her push to liberalise rules on fees also had an immense impact. “Before Mrs Thatcher, universities were very similar to public utilities – run for the benefit of staff with government money. … She was determined to introduce a much higher level of accountability for public funding and greater accountability for students as customers”.

Margaret Thatcher had been Edward Heath’s Secretary of State for Education. Peter Wilby of the Guardian writes that it was there that she developed “an abiding hatred of its culture: of ‘self-righteously socialist’ civil servants, … of ‘trendy’ teachers (and) of local authorities she couldn’t control.” He goes on to write, “As an inexperienced and diplomatically inept minister in the early 1970s, Thatcher clashed with what was later called “the education establishment”. It patronised her as an ignorant outsider, blundering into areas that she was intellectually unfitted to understand. Her revenge, taken after she reached Downing Street, transformed education at every level.”

Her revenge culminated in the 1988 Education Reform act, through which she took powers and independence away from the LEAs and schools, and concentrated them in the Secretary of State for Education. He (there was always the assumption that it would be a male) would decide the National Curriculum (teachers had virtually no say in its design or construction), he would decide the ‘programmes of study’ to be taught at each key stage; he would define the attainment targets which children would be expected to have and be assessed on at the end of each key stage.

The aim was to have a centralised system, with schools subject to market forces, competing for customers (it was never clear whether these customers were the children or the parents or both) and depending for their success on centrally published test and exam results. For Head Teachers and their teams, good results would mean greater job security, more money and less interference; poor results could threaten your job, starve the school of funds and mean more frequent inspections.

Again, as with the police, in the name of efficiency and accountability, we see the power to decide policies moving up the chain and the responsibility for successfully carrying out the policies moving down.

It was left to Thatcher’s successor John Major to complete the transformation. When he took over government in 1990, his new Education Secretary Kenneth Clarke removed the inspectorate’s independence as well: saying that the government was going to:

“take the mystery out of education by providing the real choice which flows from … independent inspection”

Every one of the 24,000 schools in England would be inspected at least once every four years. This was beyond the capabilities of the existing inspectorate which only had 500 officers. But rather than enlarging it, Clarke replaced it with an entirely new organisation, Ofsted, under his direct control. He gave Ofsted just nine months to produce an inspection framework, hire 7,500 new inspectors, train them, set up an infrastructure and hit the ground running by visiting at least 6,000 schools a year.

That they achieved this in such a short timescale was in its limited way a triumph of organisation. But the cost was appalling.

Remember the ostensible reasons the government gave for replacing the old system: Thatcher and then Major claimed that their reforms would give value for money by imposing Performance Management systems, improve the quality of education and, by letting parents choose their children’s school by comparing like with like, create ‘customer choice’ and ‘customer satisfaction’.

What Ofsted did was a parody of business efficiency: The only way they could hit their target was to simplify the inspection process. In the name of efficiency and levelling the playing field, what was being inspected and how, were standardised to a degree that would have been unthinkable before, and for very good reasons. Where earlier, HMI reports had been responsive to the unique context of each school, its history, locale, catchment area and so forth, now each report had to shoehorn the school into one of seven simplistic categories from ‘Excellent’ to ‘Very poor’, and all reports had to have identical section headings.

Once again, in order to make the act of measuring simpler to manage, the subject being measured was distorted. To compare like with like meant standardising the measure. To improve the quality of education by using the same data, meant using the measure as a test, so that in the end it was the system effectively designing the curriculum, in order to make it easier to examine.

What has been the result?

On the one hand, Ofsted’s own reports claim that improvements have been widespread [6]. However, independent surveys tell a different story: in 1999, only 35% of schools said that the benefits of the Ofsted system outweighed the harm they caused [8]. Later in 2008 when teachers were asked if Ofsted had improved their teaching, only 5% said it had. If you compare exam results when Ofsted began, with exam results in 2003, you see a small but significant deterioration except in the very best schools.

The Academies Commission finds “considerable evidence” that the current accountability framework “inhibits change and innovation”, so that the regime is failing to achieve its stated goal of improving education.”

The impact on children

On the ground the situation is much worse. Demos said in 2013 that the “target-driven accountability in the English education system is … toxic to the life chances of children and young people.”

Schools are abandoning the idea that a child’s journey through school should be designed as far as possible to met her or his needs. We have evidence that schools have responded to the pressure of league tables by “Dissuading students from qualifications that would have value for them as individuals and persuading them instead to take easier qualifications that will contribute to the organisation’s ranking.” For example, is not unknown for a school to tell parents to be told that their children could not take Art and Textiles as two subjects for GCSE as they were the same qualification. But the same school would let them take Art and Photography as two separate subjects.

When questioned, it turns out that while the children could get two GCSEs for their studies in either case, the school would be credited with two GCSEs only if the children took Art and Photography. Even if the children passed Art and Textiles exams, the school would only be credited with one GCSE because of the complex and arbitrary rules of ‘discounting’ that the department of education has deemed necessary. In other words, in at least some schools, the design of a child’s education is governed by what will benefit the school, not the child.

We have evidence that schools are narrowing the curriculum because they are

“put under pressure to achieve a particular set of (moving) targets, (so) they can find it hard to hold on to the other things as well” Since the culture of new management came into education, children have far fewer opportunities to become involved in those aspects of creativity and sport that employers say are going to be essential for their future well-being.

A House of Commons Select Committee reported that they, “Received substantial evidence that teaching to the test, to an extent which narrows the curriculum and puts sustained learning at risk, is widespread. …test results are pursued at the expense of a rounded education for children. … We believe that true personalised learning is incompatible with a high-stakes single-level test which focuses on academic learning and does not assess a range of other skills which children might possess.” In 1999 57% of teachers said that changes resulting from Ofsted inspections resulted in the quality of education either deteriorating or not changing at all. 66% said that the educational standards achieved by the pupils had either deteriorated or not changed at all.

And it seems that it is those who most need support who suffer most: The 2011 Demos and Private Equity Foundation report on the relationships between education and employment prospects particularly highlighted the way that the “Value put on academic performance tended to create situations where those who had the strongest need to develop character skills – to become ‘more resilient, better at self-direction and possessing higher levels of application’ – were least likely to be given opportunities to do so.”

The impact on teachers

But Performance Management is not just toxic for children. Mary Bousted, the general secretary of the Association of Teachers and Lecturers said at the ATL 2015 annual conference, that the profession had become “incompatible with normal life … with teachers exhausted, stressed and burnt out”. She went on, “In 2011, the latest year for which figures are available, just 62% of newly qualified teachers who gained Qualified Teacher Status that year were still in teaching service a year later.” And the reason she gives is that “…newly qualified teachers see very early on just what teaching has become and decide that they do not want to be a part of it.” Ofsted inspections were the main culprit: “Uncertainty was induced, with teachers experiencing confusion, anxiety, professional inadequacy of the marginalisation of positive emotions. They also suffered an assault on the professional selves, closely associated among primary teachers with their professional roles.” Far too often the inspectors themselves show a contempt for teaching and learning. One example demonstrates this nicely: the Senior Vice President of the Teacher and Lecturers’ Union is herself a practicing teacher. During on Ofsted inspection, she was told that the lesson she had taught was ‘Good’ rather than ‘Outstanding’. When she asked the inspector what she could do to make it ‘Outstanding’, he replied, “That’s for me to know and you to find out”.

As one Head said, “You are made to feel totally incompetent. You are made to feel that everything you’ve done for the last 20 years is absolutely useless. In 1999, the National Foundation for Educational Research found that 24% of heads and 38% of teachers took time off for health reasons after Ofsted inspections. Scanlon reports that at least one Head of Department “simply walked out in the middle of the inspection itself and never came back. In the most extreme cases, heads or teachers were off work for months due to stress-related illness.” But perhaps just as damaging is the way Performance Management has pushed teachers to adopting corrupt practices in a way that is remarkably similar to the corruption that has been so endemic in the Police.

Cheating at SATs is so widespread, that when teacher after teacher described the methods used in the Guardian in 2002, no one was very surprised.

In 2009, 70 schools had SATS results annulled or changed because of cheating. [23] In 2011, there were 292 reported cases and 370 the following year. But to get a sense of how prevalent the cheating is that does not get picked up, one has to go on to parents’ internet websites, where mother after mother worries about the stories of teachers ‘helping’ their children and agonise over whether or not to object.

In another report in 2013, one school one teacher is quoted as saying, “Nobody had bothered to get these kids to complete coursework – just give them a C,” “Then the exam board asked for samples of pupils’ work to moderate the marking. The deputy head then asked teachers to ‘help’ the students complete 18 months of coursework in a fraction of the time” “At present honest teachers have only two choices: either ignore the injustice and continue to be punished for results which are lower than neighbouring schools which cheat, or blow the whistle on friends and colleagues – an extremely difficult thing to do.

The impact on Schools

It is not just teachers who are being corrupted. Whole schools are affected. “Statistics published in December by the exams regulator, Ofqual, show a 61% rise in the number of schools and colleges found guilty of malpractice last year, with 217 penalty notices issued, one for every 30 schools or colleges in the UK.”The reasons this happens are quite clear:

“The incentives for schools to push the boundaries to raise results seem very strong, and yet the disincentives, in terms of penalties and publicity, seem weak. …This can penalise schools that have acted properly and then find themselves competing, through league tables, against others that may not have.”

Concerns have also been raised about Ofsted’s judgements on schools with the poorest and most challenging intakes. The old inspectorate took a school’s context into account, for example recognising ‘schools in very poor areas . . . which could not . . . match the achievements of the higher categories but . . . did splendid social work’. But Ofsted was afraid that this ‘might embed low expectations in some schools and let down the most needy, so they scrapped it. The result was ‘a 1995 study which reported that 90% of schools in the two highest social contexts were judged favourably by Ofsted, compared with only 10% in the two lowest social contexts.

The impact on policymakers

As Mary Boustead said,“The findings of the (Public Accounts Committee (PAC), February 2015, report on School Oversight and Intervention) are devastating. In essence, our education system is being run on a wing and a prayer – and if something goes badly wrong, the Government relies upon someone being brave enough to speak out. Who knows what else is going on under the radar. … The PAC finds that action to prevent decline or continuing poor performance in schools ‘is rarely achieved.’ ”The assumption is that the best way to improve standards in education, is to make judgements about the effectiveness of school leaders and teachers, in terms of specific criteria. The people who originally designed Ofsted’s methodology said that a school’s performance against these criteria would be an indicator of how the it was doing across the board. This was based on an assumption that the test would act in the same way as statistical sampling, from which you could extrapolate how the rest of the school was doing. But as we know now, it did not work out that way.

But what is astonishing, particularly in an educational context, is that no one was willing to accept that things were not working out as expected and no one was willing to do the rigorous, scientific, educational process, of understanding in what way it was not performing as expected, and for what reasons, in order to design a better process. In order to learn from experience, as every teacher knows, you have to accept and analyse your mistakes. That is what we ask of children. We should expect it of our teachers and of the education policy makers as well.

Instead we have an arrogant and irrational system that differs from the one it replaced only in that it claims to be rational and evidence based. How false this claim is, was revealed in 2008.

Just before he became Prime Minister, Tony Blair revealed that he and his wife had chosen not to send their sons to the school in their local catchment area, Islington Green, but instead to send them to the more prestigious Oratory School in Knightsbridge. This was in spite of Islington Green School being rather good – if less fashionable than the Oratory School. The Times Educational Supplement said of Islington Green,“Ken Riddell’s design and technology department had been described as a centre of excellence in the previous inspection report, and had improved since. It was just one of a number of robust departments, with a mix of experience and new enthusiasm, drawing in not only local families but parents from neighbouring Hackney. Morale was good, GCSE results were respectable: 38 per cent were getting five A*-Cs.”

There were rumblings in the press about the Blair’s decision. It so happened that on the day Blair became Prime Minister in 1997, the school was told that it had failed its week-long Ofsted inspection. The staff were stunned. Ken Riddell told the TES,

“We didn’t believe it, because we knew it wasn’t true. We thought it was a mistake that would be sorted out.” [idem] . The School was put in Special Measures, and its reputation was ruined.

Eight years later, in 2005, following a request under the Freedom of Information Act, the TES learned that the original inspection had not failed the school at all. But Chris Woodhead, the then Chief Inspector of Ofsted – who had not visited the school – chose to disagree with his own inspectors’ findings in a way that supported the Blair family’s decision. He sent in another team to back him up. But they too concluded – unanimously – that it was not failing. Woodhead overruled them as well. When questioned later, he said only that the decision had been within his powers. As the School’s headmaster said, the pupils believed for seven years they had been to a rubbish school and that their teachers were incompetent.

“Placing the school in special measures had been catastrophic for staff and pupils. Many colleagues who worked at Islington Green have suffered in their careers because of this unjust decision. However, the greatest victims have been the children of Islington” [29]

“The failure had devastating consequences for the school, which became notorious when pupil violence and behaviour soared out of control. There was a mass exodus of teaching staff, including eight heads of department and deputies, and a slump in GCSE results which dragged it into the bottom 2% of all schools nationally.” The school stayed in special measures until Woodhead resigned in 2000. The Blair’s children went to the Oratory school and no one needed to ask why their parents had not sent them to school in Islington.

The regime that had been designed to replace supposedly inconsistent and arbitrary inspections with evidence-informed policy, had started to even more inconsistent and arbitrary inspections leading to policy-based evidence.

Worse, the data Ofsted has been collecting is almost certainly unreliable. The House of Commons Select Committee on Children, Schools and Families in their Third Report of Session 2007–08, said, “The evidence we have received strongly favours the view that national tests do not serve all of the purposes for which they are, in fact used. The fact that the results of these tests are used for so many purposes, with high-stakes attached to the outcomes, creates tensions in the system leading to undesirable consequences, including distortion of the education experience of many children. In addition, the data derived from the testing system do not necessarily provide an accurate or complete picture of the performance of schools and teachers, yet they are relied upon by the Government, the QCA and Ofsted to make important decisions affecting the education system in general and individual schools, teachers and pupils in particular.” And the very act of collecting this unreliable data is done at the expense of the education of the very children the testing is intended to benefit. The Committee report continues with a section headed, “The consequences of high-stakes uses of testing”: “We consider that the measurement of standards across the full curriculum is virtually impossible under the current testing regime.”

New Public Management created a system of accountability in our education system which is “toxic to the life chances of children and young people”, which has demonstrably demoralised teachers and schools, which has in well-documented cases encouraged dishonest practices and yet which had failed to produce any accurate measurement of standards. The most astonishing is that in the twelve years since the Select Committee Report was published was published, nothing substantial has changed. The masters of education will not recognise the evidence and refuse to learn.

It is interesting to note that in 1979 in spite of the fact that Islington Green School was still technically failing, Roger Water sought out their school choir to sing the chorus on the Pink Floyd recording of “Another Brick in the Wall”. The words they sang are as follows:

We don’t need no education

We don’t need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers leave them kids alone

Hey! Teachers! Leave them kids alone

All in all it’s just another brick in the wall

All in all you’re just another brick in the wall

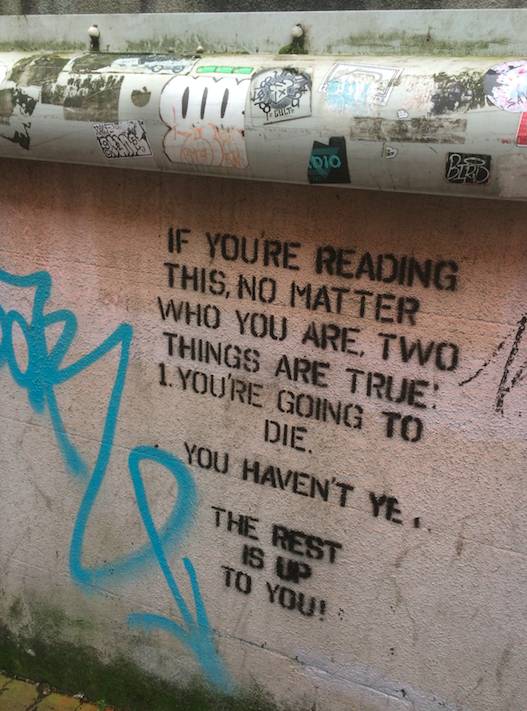

Two new blogs I’m fast becoming a fan of. The first is The Red Hand Files by the Australian singer/composer/actor Nick Cave. The second, Brainpickings by the American reader and writer Maria Popova. Well worth a few minutes of your time. The headline above refers to a recent post by Nick Cave.

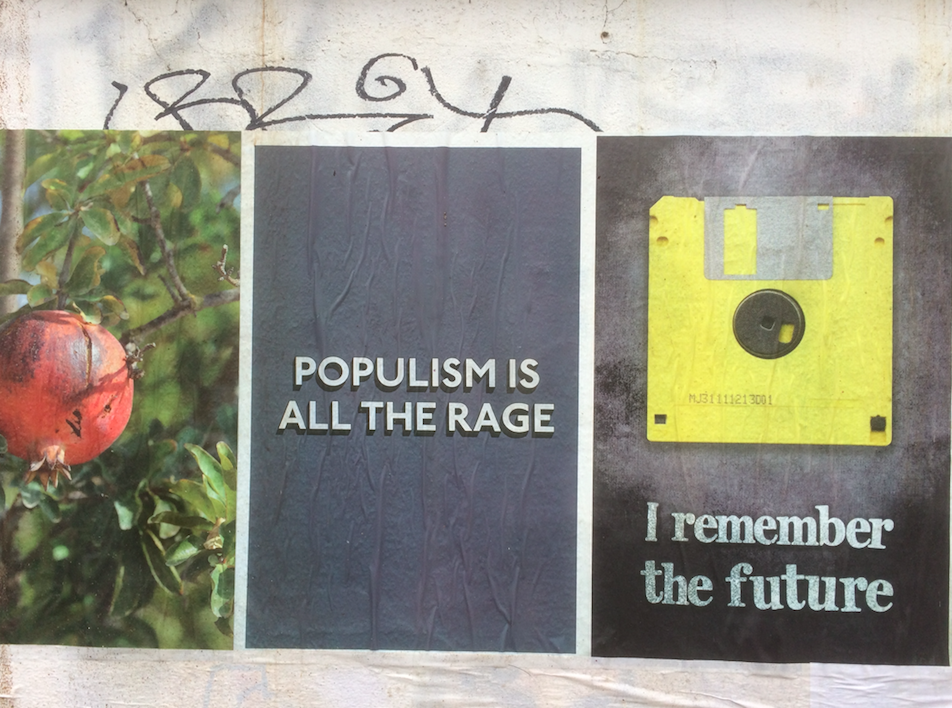

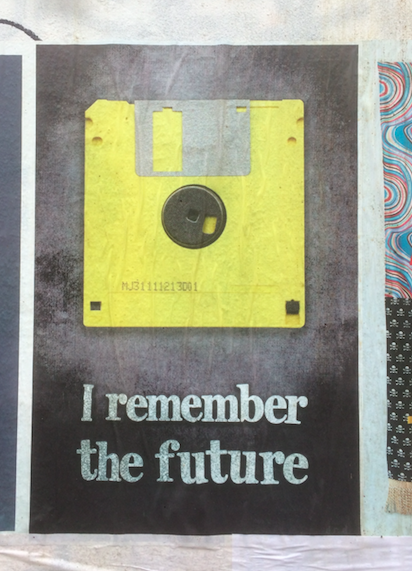

Image unrelated (Brighton, UK, last week)

“Science does not need mysticism and mysticism does not need science. But man needs both.” – From the Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra.

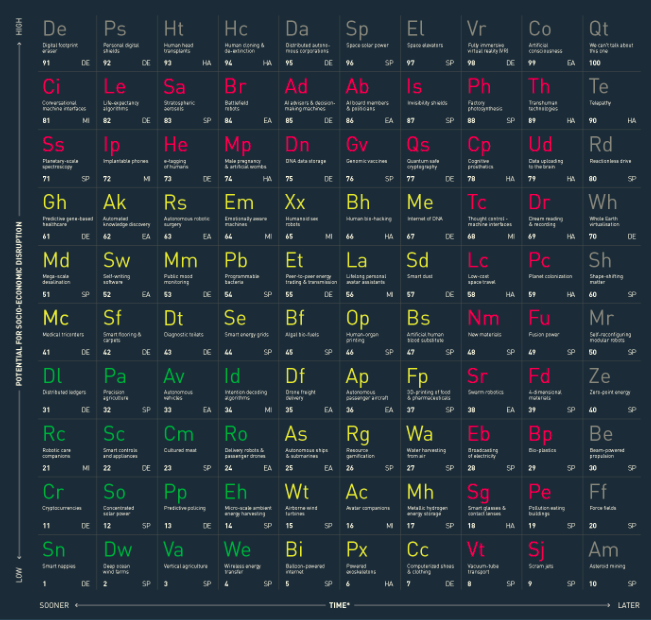

From children’s books and streets of the future (see yesterday’s post) to the distant future of energy. especially zero-point energy and metalic hydrogen energy storage and transmission. Both feature on my table of distruptive technologies (17 out of 100 entries are energy related). If you don’t know about these they are very much set in the sci-fi fringe of current physics, but both could be possible one day. Zero point energy is essentially the idea that the universe is not made of static particles, but is, in fact, a sea of constantly moving waves or fluctuating matter. Metallic hydrogen is when the gas is made to change to a metallic state (physical form). This state has never naturally existed on Earth before, but it has the potential to become a superconductor enabling zero-disipation energy transmission. It could also allow storage using persistent currents in superconducting coils.

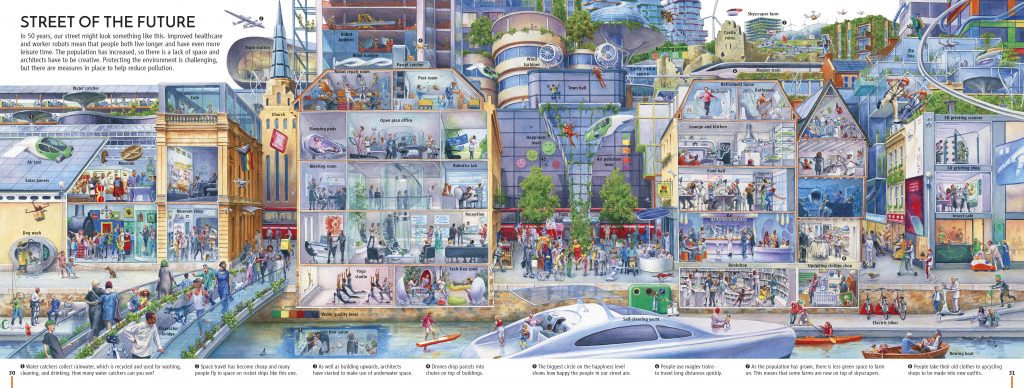

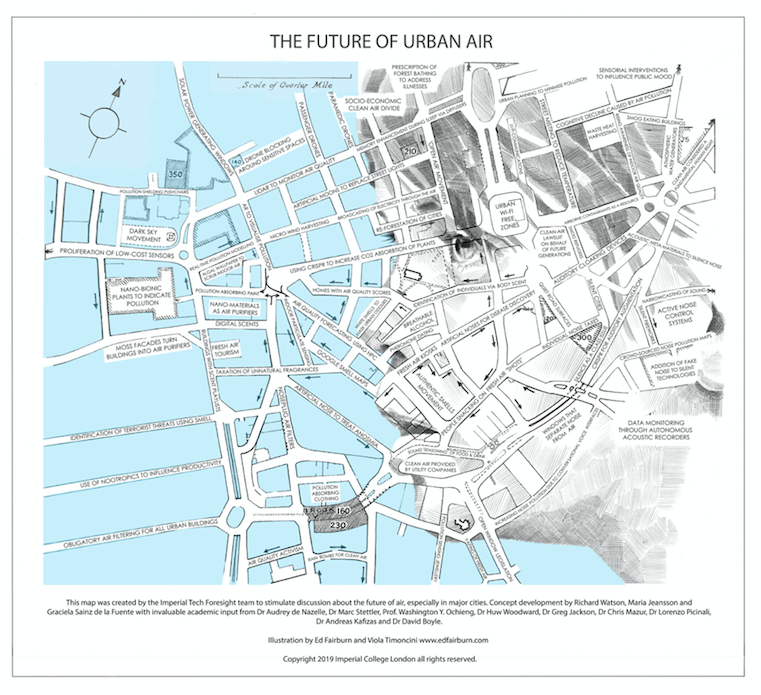

I seem to be carving out a niche with books about the future for kids. I’ve just contributed to a second, the updated version of A Street Through Time, published by DK £10.99. Works well, I think, alongside the future of air map (not really for kids).

The best bit from the BBC series Years and Years (set in the near future). Watch from about 2-minutes in (2:40 to be precise). The £1 t-shirt (more often the £5 jeans and fast fashion generally) is a perfect way to demonstrate how ethics go out of the window in the face of money (“principles aren’t principles until they cost you money”). The removal of human contact in banks and supermarkets is also spot on.

I’m not sure this is a trend as such, but the concept is certainly interesting. On top of the Copenhill power plant in Copenhagen the architect has placed a dry ski-slope. Why? Why not? The architect uses the term “hedonistic sustainability”.

I’ve started buying old watches, notably old diver’s watches from the 1960s and 1970s.

They are generally cheap as chips, unless you pick a big brand. The one in the picture is a fairly obscure Sicura from the 1960s (probably). It’s rather worn, which is why I like it.

It cost me £110, so if it gets lost I wouldn’t lose sleep over it, although the more I wear it the more attached to it I become. If only I knew it’s history. Who wore it and where?

One of the best bits about the watch is it isn’t that great at telling the time. This one gains about 40-minutes a day, unless I wear it to bed, in which case the loss drops to 10-minutes depending upon how much I toss and turn in bed (it’s self-winding). The point is I always know roughly what time it is, and if it’s absolutely essential that I do something bang on time I can always look at the clock on my phone.

Anyway, I think there is something loosely liberating about not knowing the exact time.

What’s this got to do with the future? Nothing, except that if pushed I suppose one might start to ponder the nature of time and the relationship of past, present and future. And when is ‘future’ exactly? I was speaking with a friend and sci-fi writer Lavie Tidhar a while back and his working definition of ‘future’ was when things got weird. But that’s now surely? My own ‘future’ tends to be 10-15 years out, but personally I’m more focussed on the present these days. Anyway, the future was always a bit of an excuse to get people to engage more with the present.

As for clock watching, I think the purpose of clocks generally is to be prepared for future events. That’s possibly the worst load of mumbo jumbo I’ve ever muttered in a blog post.

Just had a lovely lunch at Riddle & Finns (in Brighton) with my web guy Matt Doyle (from Robertson NSW). I should perhaps have used this image above (seen pasted to a wall in Brighton) for yesterday’s post about dead tech.