How are you? How’s life? In 2015, a YouGov survey found that 65% of the British (and a whopping 81% of the French) thought that the world was getting worse. But it’s not, it’s been getting better for decades. On almost any measure that matters, life is demonstrably better now than it has been in the past. In fact, 2016 was the best year for ever for humanity according to Philip Collins writing in The Times. In 2016, extreme poverty was affecting less than 10% of the world’s population for the first time. If that’s not cause for celebration, 2016 also saw global emissions from fossil fuels falling for the third year running and the death penalty becoming illegal in over half of all countries. Nicholas Kristof, writing in the New York Times, echoed the optimistic perspective: Child mortality is now half what is was back in 1990. More than 300,000 people every day are gaining access to electricity for the first time. Similar good news stories can be found in statistics about human life-spans (more than double what they were 100 years ago – a mere 31 years in 1931, for example), the number of women in education and work, basic sanitation and clean water. It’s the same story with literacy, freedom and even violence.

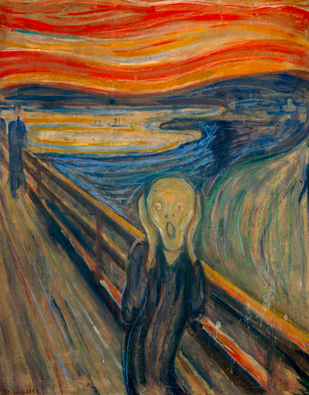

So why does it feel like things are terrible? Why are so many people longing for the good old days? The answer, most likely, is global media and ubiquitous connectivity. Ignorance is no longer bliss. We are exposed to endless headlines about Brexit, Trump, Putin, Syria, terrorism, climate change and North Korea 24/7. There’s no escape.

Our response to this tends to be one of two things. Either we conclude that the world is indeed going to hell, so we might as well enjoy ourselves, or we become profoundly anxious, depressed and cynical about everyone and everything. But as members of what’s been termed the New Optimist movement (a term meant to evoke Richard Dawkin’s New Atheists), point out, this doom and gloom is deeply irrational. The pessimistic mood simply ignores the facts and underestimates the power of the human imagination. Moreover, while a worrisome mind was useful in the past (when looking out for threats outside your cave could literally save your life), use of the same fight or flight mind-set today can lead to spirals of despond. The fact that news now circulates the globe faster than it can be properly analysed doesn’t help either. Add to this a deluge of digital opinion which is at best subjective and more often false or misleading and it’s hardly surprising that so many people feel unsettled and disorientated to put it mildly. Another explanation for pessimism lies in our cognitive biases and especially our general inability to properly asses risk or probability. For example, more people died in motorcycle accidents in the US in 2001 than died in the Twin Towers attack on 9/11.

So, should we relax? Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that we need to put things in proper perspective, look at the real numbers and assess the actual probabilities. No, in the sense that just because we’ve had it good for the last 50 or 100 years doesn’t mean that our run of good luck will naturally continue. Maybe the last 100 years is simply a blip (extrapolating from recent personal experience or data is usually what goes wrong when it comes to long-term forecasting).

Another downside of global connectivity is that risk is now globally networked and systemic, meaning that one lunatic with the nuclear codes or a nasty biological virus could wipe us all out tomorrow. There are still things that could go seriously wrong, as David Runcimanm, a Professor of politics at Cambridge, points out.

OK, so around 120 countries out of 193 are now democracies (up from 40 in 1972), but this could change. Cyber-terrorism could bring us to our knees for extended periods too and while people throughout history warning of the end of the world have always been wrong, they only need to be right once. Hence, a degree of caution, or cynicism, can be useful. It’s also worth noting that if people become too depressed about things they tend not to be motivated to fix things (although, similarly, it might be argued that if you are too optimistic a similar rule applies). Any mind-set can become a self-fulfilling prophesy. Also, while it’s indisputable that globally, or on average, things are good and getting better, this isn’t true for everyone, everywhere. Local exceptions apply. Furthermore, a more nuanced criticism of the rational optimistic view is that saying things are great is a great way of saying don’t change anything, which is to say leave free market capitalism and political structures well alone.

Overall, people will choose to believe whatever they want to believe and choose the facts that support their world view, but one thing that’s still missing perhaps is vision. We are increasingly stuck in the present, ignorant of our deep history and seduced and distracted by an internet that’s fuelled by our attention. If, instead of giving the internet and 24/7 media our time, we spent our time thinking about how we, as a species, would like to live now and where we would like to travel in the future I suspect that a lot of the current anxiety and pessimism would evaporate. In other words, we should worry less about what we think is happening now or might happen next and start taking about what we want to happen now and what we want to occur next.