Here’s some possible evidence to support the idea that the change argument can be a bit of a myth. Around 90% of the US workforce is employed in occupations that existed 100 years go.

The Observer, 06.09.15 (P20).

Category Archives: Work

The Architecture of Ideas

I’ve written extensively about how physical spaces influence thinking (e.g. Future Minds, Fast Company etc.), but I didn’t realise until recently just how much research there was on this. For example, Joan Meyers-Levy and Juliet Zhu, two Profs at the University of Minnesota, ran a study that found that high ceilings activated abstract thinking and thoughts of freedom, whereas low ceilings activated concrete thinking and thoughts of confinement. In other words, high ceilings are good for inspiration and big idea generation whereas low ceilings are good for small detail and implementation.

A further twist on this is the idea of cells, hives, dens and clubs espoused by Francis Duffy at DEGW architects. The basic idea here is that hive offices suit routine or low level process work with low levels of social mixing and autonomy, cell offices facilitate focused brain work with little social interaction, den-type offices suit team work and club offices do a little bit of everything.

This possibly explains why my solitary home office is useful for some tasks, my busy boat office for other tasks and the manic café best for something else.

Related.

http://ergo.in/paw_funatwork.html

http://www.sussex.ac.uk/Users/geraldin/Publications/AUIC-final.pdf

http://www.flexibility.co.uk/flexwork/offices/facilities4.htm

The Future of Work

I don’t know Jacob Morgan. I’m sure he’s a nice guy, but I think he suffers from being too young. Or perhaps he is just too focused on technology.

He has just written a very good article called 8 Indisputable Reasons Why We Don’t Need Offices. He has a point. 8 in fact.

After all, why, in a world of global connectivity and collaboration (and endless branches of Starbucks) do we need physical offices, especially if the work that people are doing in offices is increasingly information work that can be done anywhere in the world?

He quotes a statistic from a survey by Regus that states that of 26,000 businesses across 90 countries, 48% work remotely for at least 50% of the week. But look at the motive here. What does Regus sell? Office space for people that don’t have or need a full-time office. It is in their interest to persuade companies to downsize, much as it is in the interest of certain technology forms to push teleconferencing.

Morgan points wisely to the fact that companies save money when offices become virtual and employees save time when they are not physically moving to and from a physical workplace. There’s even an argument, not totally screwy, that employees are more productive when they work from home.

This is all good. But who really benefits from all this and what is the ultimate end result? The answer, I’d argue, is that it’s companies that benefit the most from this. Companies save money, lots of it, not simply because they can reduce the size of their physical workspaces, but because once employees are out of sight it is easier to shift them towards towards freelance and ultimately zero hours status.

Morgan is spot in in his conclusion that organisations need to implement more flexible work environments (to which I’d add contracts), but the fact of the matter is that looking just at money or even time saving is only one side of a complex coin and he, like many others, confuses efficiency with effectiveness.

Work shouldn’t just be about money. Work is also about community and meaning.

Work provides a sense of friendship and community, a type of friendship and community that can be partly enhanced but not fully replicated digitally.

More fundamentally, physical offices provide a critical boundary and balance, which is important to our sense of identity. If everywhere becomes work then work is all that we will become.

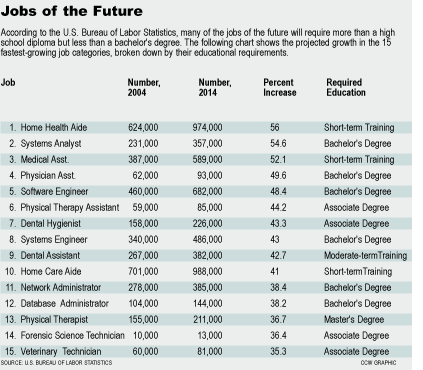

Jobs of the Future

Funny, you don’t write about jobs of the future for ages then two requests come along almost at once. Here’s a link for a small piece I wrote for today’s Guardian newspaper on jobs of the future and here’s another – quite different – article on jobs of the future for MSN careers written by myself and Ian Pearson.

A Case for Slow Business

We are killing ourselves, slowly but surely, because we are obsessed with the idea of speed. We need to get more done, we think, and to achieve this goal we need to move faster. It is a need it now, get it done, 24/7, globalised world where adrenaline-fuelled financiers and assorted Type-A types, measure everything, and everyone, with narrow numbers and questionable costs.

Education, for example, is now less about socialisation, character building, values or the cultivation of thinking for the sheer pleasure of it. It is now more about measurable outcomes, examination results and fast-track entry into the world of paid-work. Schools are now factories that buy in materials at the lowest cost and throw out students that do not fit, or question, this standardised model.

This is quarterly capitalism gone mad. A giddy world where short-term financial gains for the select few are huge, but so too are the longer-term costs for everyone else. It is a world where profits are privatised, but costs, especially those measured in terms of long-term damage to the environment, to individual human health and to local communities are shared by all.

Our obsession with speed is especially prevalent within the new economy, the online economy, which, it seems to me, is all about our greed for immediate attention and instant gratification.

The personal web, along with personal technology, is about fast downloads, real-time updates, quick pixelated fixes and an almost autistic focus on me right now, which very often has little relationship to reality because me right now is filtered, digitally enhanced, and photo-shopped. This is a world where connection and familiarity are rising, but one in which context, deep thinking, quiet reflection, sustained focus and above all human intimacy are declining.

Of course, in an accelerated world, nothing lasts for long. Remember Second Life, MySpace, Orkut or Friendster? Many people don’t. Many people also fail to recognise that companies such as these – and the people than run them – can go from hero to zero faster than a freshly qualified accountant can say wasting asset.

But that’s OK, because in an accelerated world our collective memory is measured in minutes and we don’t remember things, especially things that go bad, don’t work or end up hurting us.

Take the current financial crisis, for example. This was caused by the creation of easy money – we made it too easy for people to borrow money. So what are we doing right now? We are making it too easy to borrow money – we are bailing out bust banks (and then forcing them to lend), subsidising borrowers and taxing creditors – all with the effect, as far as I can see, of making pre-existing structural deficits even worse.

We fall for myths like the one that says: “things are different this time”, so we end up being spun in an endless cycle of unrealistic promises, targets and goals, few of which ever come true or, if they do, the human costs can be immense.

None of this is sustainable, in my view. Our obsession with speed, with short-term thinking and narrowly defined outcomes is moving society backwards, not forwards, at an accelerating rate. Furthermore, our need for speed is disorientating and dividing us, much as the primacy of the individual and of individual rights is undermining community and society as a whole.

I’m sure that most people are familiar with the idea of Slow Food and perhaps Slow Cities. What I’d like to promote, therefore, is the idea of Slow Business and in particular Slow Management and Slow Leadership.

What I’d like to suggest is the idea that if we moved slower, thought more and did less, we would not only end up getting more done, but that we’d all be healthier and happier too.

I doubt whether most individuals or institutions are ready for this. Some are. Family businesses and cooperatives think along similar lines already. But I doubt whether many, if any, quoted companies can deal with the idea. No problem. Change can start anywhere and eventually even the world’s largest organisations will, I suspect, be forced to try something new.

So what does Slow Business look like?

To my mind it is the leading or managing of economic activity that incorporates the principles of slow thinking. It is calm, reflective, untroubled and most of all has its eyes firmly set upon a distant objective.

Fundamentally, it looks at things from a whole cost point of view. It does not buy the cheapest, especially when this has a high social cost, and it looks at the wider and longer-term impacts of economic activity. It measures things differently and focuses first and foremost on employees rather than customers, because if employees are not treated well how can they possibly make customers happy?

So, without further elaboration, here are my five principles of Slow Business.

1) Full social and environmental accounting

We must end our obsession with quarterly earnings and 12-month ‘results’. We should think more in terms of 10 and 20-year plans and link these plans more closely with social, human and environmental costs. For example, Spain and Southern Europe are seen as being “uncompetitive” by Northern Europe. On what basis? If you measure everything with GDP then sure. But if you measure social cohesion or happiness then perhaps it’s they that are uncompetitive.

2) A sense of provenance and place

I think Globalisation as an idea is unravelling. I have no issue with the free movement of capital, goods, people or ideas, but I believe that people have a right to be told where things are coming from physically and metaphorically. If they are given this information behaviour might change in favour of more local options. People may choose not to buy certain things, because they believe that products are travelling too far (environmental costs) or perhaps they won’t like the objectives or purpose of a company (social costs).

Provenance is really about adapting the language and information already used by food and especially wine companies and applying this to industrial products and services. Essentially, it’s about caring about and communicating by whom, where, how and when things are produced. Most of all, it is about knowing who you are, where you have come from and where you are heading as an organisation. And to do all this one must be physically and mentally embedded in a particular place.

3) A sense of fairness

Employees don’t want very much. They want money, meaning, recognition and respect. But they also want fairness. If a leader creates value I have no problem with them being well paid. Equally, I have no issue with inventors or entrepreneurs earning millions, even billions, when they create something that’s very useful. But I do have an issue with leaders (including politicians) being paid for mediocre results, especially over an extended period.

I would like to propose that people at the head of organisations are paid no more than 50 times what the lowest paid worker is paid unless they can demonstrate, without question, that an idea they have had has resulted in a desirable outcome. I would also like to propose that an outcome is directly related to something of substance, ideally something that is created not something that is traded or speculated.

4) Recognise the importance of doing nothing

This is perhaps the most important idea. At the moment we are wedded to the thought that every minute of the day must be productively used. For example, that physical and mental presence is a prerequisite of employment. This is nonsense. Looking out of the window for an extended period, for instance, could be the most productive thing that someone does if it results in a good idea.

Similarly, doing nothing in the sense of sleeping or resting is hugely under-rated. Let’s bring back the siesta and spread it across the world because rest is essential, not only to proper physical and mental health, but also to the creation of new insights and ideas. Anyone that knows anything about creativity will recognise that it is only when we switch off or do nothing that ideas and insights come. In short, if you want an idea you need to stop trying to have one and the best way to do this is to stop working for a while.

Hence I would like to propose that we not only bring back or introduce the office siesta but that companies insist that all employees take their full holiday allowance and are not contactable when on vacation. In fact you should get fired for not going away. In a similar vein I’d suggest that we ritualise the switching off of work related mobile devices when at home and that we insist that once a week, at least, we have a Tech-No day, where employees are forced to meet in person or write letters not emails.

5) Eat lunch

A link directly back to Slow Food. We need to eat, but we seem also to need to justify the time spent doing it. Sometimes we sit alone at our computer while we eat a sandwich. Sometimes we miss lunch altogether: we go to the gym to work out aggression before plunging back into work. Why? When, indeed, eating in the middle of the day is a natural and healthy moment to do so — sustaining energy, allowing digestion and feeding conversation.

We need to reclaim lunch. It is where loyalties are built and where ideas are exchanged. We should therefore think about lunch more. Employers should value employees as people who need to eat. Employees should value employers as people for whose sake – among others – they eat. And maybe the ritual meal, the nourishing meal, the creative meal, food not as a weakness, but as collaboration tool, can come back into business.

In the new world of work, modesty is no longer a virtue

Let’s talk about me. This focus on “Me” is a new development, especially in the UK. Traditionally, the British have been modest about their achievements.

Take the Industrial Revolution. It was pure luck. It could have happened anywhere. Penicillin? Serendipity. The jet engine? Somebody else would have eventually come up with the idea old chap. Nothing to really shout about.

The ego in Britain was historically kept in check by self-deprecation and this became a hallmark of British culture and comedy. The class system may have had something to do with it too. Positions were fixed and there wasn’t much point trying to change things when destiny was largely determined at birth.

But more about “Me.” In the United States people are taught from birth that meekness is a weakness. Maybe this developed due to the early need to fight wild Indians or bears. Who knows. Whatever the cause, fluidity and forwardness has been feature of American society since its inception. America is more egalitarian than Britain and hard work can therefore pay off. Nowhere has this been truer than in New York, where boasting rarely results in a roasting and putting oneself ‘out there’ has always been a basic requirement, not only for work, but for finding love and happiness too. Now, it seems, the rest of the world is loudly following in New York’s footsteps. Extroverts are in the ascendant and introverts just never make things happen. But why is this? I think the reason is twofold.

First, in the world of work, the cogitative elite has become globalised and this has resulted in a hugely competitive landscape where you are only as good your last project and everyone is, so the theory goes, after your job. The world is now flat. It’s quarterly and globally accelerated capitalism and there is no time for hanging around or sticking your dim light under a damp bushel. To mix the metaphors even further, it’s a totally different kettle of piranhas out there these days.

Now it’s all about shouting the loudest to get seen – and to get paid. It’s all about economic free agents, road warriors, personal branding, LinkedIn profiles, high profile internships – often bought at charity auctions – and loading your digitalised CV with search engine friendly keywords. Even our physical work environments have become loud. Walls that were once white are now painted in strong colours or plastered in professional graffiti, supposedly to stimulate our creative thinking. Where once we had quiet and reflective private offices we now have casual open-plan layouts, supposedly for the same reason.

If you think this is an exaggeration then you obviously haven’t heard about Facebook’s Menlo Park office, which has all this and more. Even the meeting rooms have extrovert names and the signs say things like: “Move fast and break things.” Everything is now social and team based and if you don’t enthusiastically join in there is the suspicion that there’s something wrong with you.

But what if you don’t want to be the life and soul of the daily office party? What if you don’t want to talk, but prefer to be left alone to think or indeed code? It’s as though a bunch of kindergarten kids have taken over the whole world.

The second reason that modesty is now a travesty is technological, although this links with and strongly supports the forces of globalisation. We now live in a world where it’s much easier to sell yourself to a global audience and to tell the world how wonderful you are– even what you’re up to right now. And because things are so hyper-competitive, this often means wild exaggeration and a heavily image-enhanced portrait. A booming Type-A job title like “CEO’ also helps, even if the company you work for is just you in a spare bedroom

Of course, you can’t just blame the individual for this ego inflation. At school we are all told that we’re all ‘special’. There are classes for the ‘Gifted and talented’ and experts tell us that anyone can be a genius. And governments encourage this too by insisting that anyone can and should go to university.

A consequence of all this is the increased emphasis on the person. Personal technology means it’s now more about our individual whims and wants. We can now have our newspaper and our cup of coffee our way (i.e. personalised). Technology, such as television, that was once communal has become individual.

This is obviously a good thing, because we can now all watch what we want to watch when and where we want. But one result is that we no longer have to compromise and sometimes accept what other people want to watch, which is not especially social. Overall, I believe, this is starting to create an intolerance of others, including other peoples’ likes, dislikes, opinions and foibles. But who cares, because you don’t really need anyone else nowadays right?

Something similar is happening with friendship. Peer pressure is now networked so one needs to constantly sell oneself and what one is doing. You need to be constantly having an enormous amount of fun and hanging out with people even more beautiful (i.e. even more photo-shopped) than yourself. In sum, it’s a world where fame and fortune are fleeting, so you may as well get your job application, funding foray or date in before everyone else.

Demographics impact here too. In some places there are more single women than single men, so the stakes of each date get higher. And the same demographic force applies to the availability of jobs.

But here’s the thing. Our newly extrovert nature, along with our newly found connectivity and digital friendships, are hiding a dark side. We are now alone more than ever. Our connectivity is a sham. We are indeed connected more than ever, but connected to what or whom? To people with whom we can share our deepest hopes and fears? I fear not. We have exchanged intimacy for familiarity and our so-called friends are about as long-term and resilient as our jobs. As for everything becoming social, this is true on a very superficial level, but underneath I believe the very opposite is happening.

I don’t know about you, but it somehow felt better back in the days when the meek were in line to inherit the Earth. One somehow felt that something of substance might be happening in those quiet offices and hushed corridors of power.

I’d trade a quiet, mild mannered meek for a noisy, narcissistic geek any day.

Size does matter and small is best

I really must start writing my monthly brainmail newsletter again soon because much of this material is perfect for brainmail. Nevertheless, here’s a little gem that caught my in-box yesterday morning.

In an experiment conducted (by teams?) at UCLA and the University of North Carolina, two-person teams took an average of 36-mins to assemble 50 Lego pieces into a human figure. The same task took 52-mins for four-person teams.

Apparently, forecasting errors grow larger as teams get bigger and expanding a team’s size can negatively impact coordination, diminish members’ motivation, and increase conflict. (Via Harvard Business Review).

Culture of extended work hours

Here’s a gem. A study by Mary Noon at the University of Iowa and Jennifer Glass at the University of Texas says that telecommuting allows employers to expand workdays and create an expectation that staff will be available in the evenings and over weekends (Via Harvard Business Review/Monthly Labour Review).

On a related note, 20% of parents with children aged 10 only see them properly once a week according to a study by the Family and Parenting Institute in the UK.

Stat of the week

Getting paid increases the risk of you dying according to study.

Classic. You have a slightly higher chance of dying in the days after you get a paycheck, bonus, or Social Security payment, say William N. Evans of the University of Notre Dame and Timothy J. Moore of the University of Maryland. For instance, during the week when the 2001 U.S. tax rebate checks arrived, mortality among 25-to-64 year olds increased by 2.5%, and during the week when dividends are paid to Alaskans from the state’s Permanent Fund, mortality increases by 13%. Higher levels of activity such as driving and recreation after money rolls in are the likely causes of the effect, the authors say.

(Via Harvard Business Review).

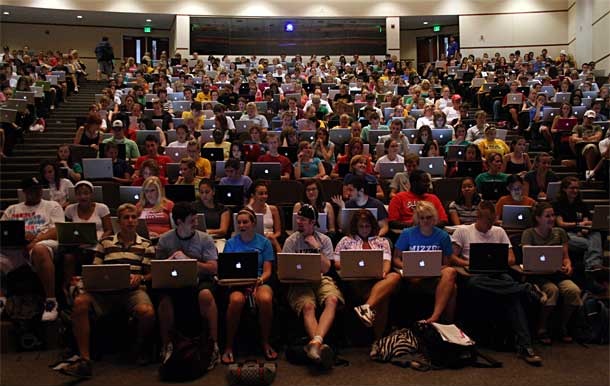

Image of the day

Just been cruising around Lynda Gratton’s blog on the future of work and found this gem of a picture. Question is, of course, is this an indication that Apple has peaked and one should sell shares or an indication that the company is still going up and one should buy shares? The other question, perhaps, is whether or not anyone in the picture is paying attention!

Afternoon update. Just found this too – the world of work that awaits…