“The poor were fat and the rich were lean.

Nearly all could preach, very few could sing.”

By Les Murray.

“The poor were fat and the rich were lean.

Nearly all could preach, very few could sing.”

By Les Murray.

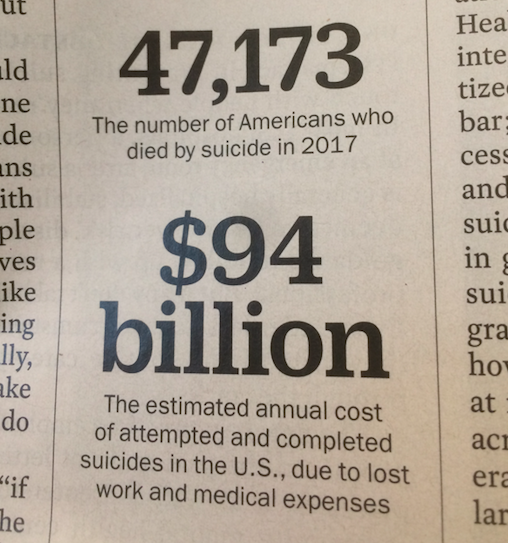

You might think that the cost of suicide, especially the cost to work, might be the last thing people would be thinking about.

I may have posted this before (I’m getting old and forgetful). From the New York Times

Writing in the Washington Post, Brigid Schulte, a time-use researcher and author of Overwhelmed: Work, Love and Play When No One Has the Time, quotes an article in a 1959 edition of the Harvard Business Review saying that: “boredom, which used to bother only aristocrats, had become a common curse.” Similarly, in 1960, the US broadcaster Eric Sevareid thought the gravest crisis facing America was: “the rise of leisure”, although this, is an old argument indeed – “Idleness and lack of occupation tend―nay are dragged―towards evil” as Hippocrates observed in Decorum. But we should be careful not to confuse being lazy with being idle. What might be termed ‘strategic idleness’ can pay dividends, as Jack Welch, former CEO of one of the world’s most admired companies, General Electric, would attest. Welch famously spent an hour each day looking out of the window, while Lord Melbourne, a former Prime Minister of Great Britain, praised the value of what he termed “masterful inactivity.”

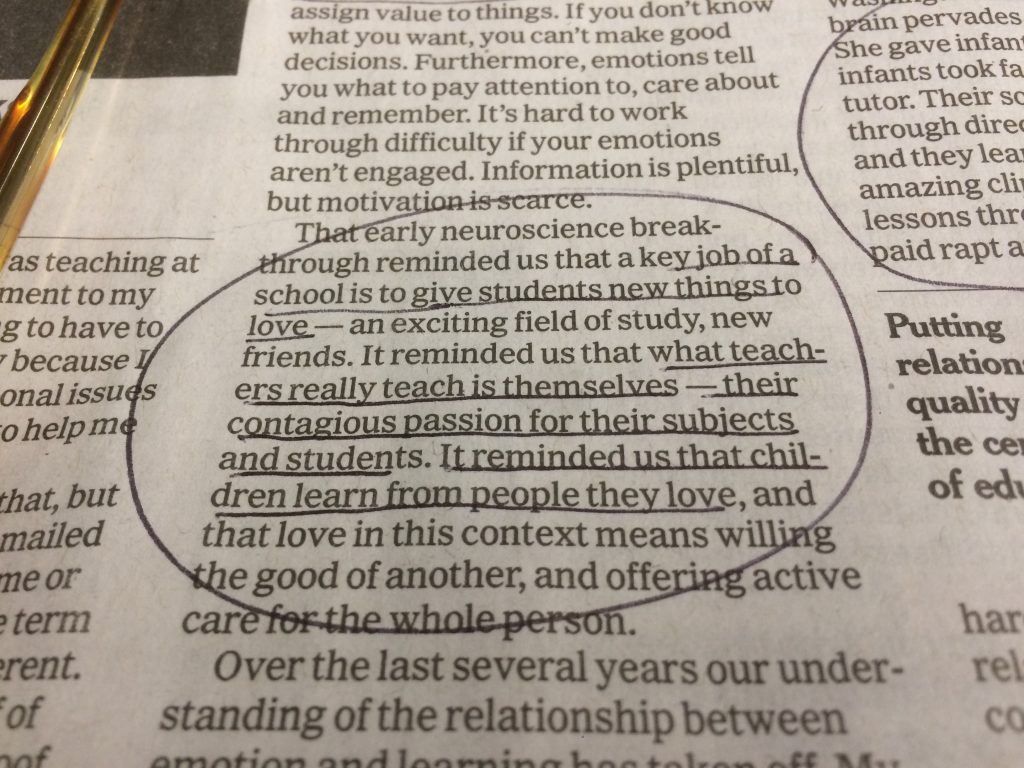

Sorry, cleaning up my desktop and found this. No idea where it’s from.

Back in November 2016, when Trump was elected President of the United States, Erik Hagerman had a plan. Distressed by the hoopla of US politics he decided to stop reading the news. His experiment was part protest, part a coping mechanism and part extreme self-care. Living alone on a pig farm in rural Ohio this was clearly achievable in ways that it might not be had he lived somewhere else like Chicago. Hagerman travels into the local town, Athens, to buy coffee and to shop, but he keeps up his news blockage with the help of white noise from his headphones and an agreement with family and friends not to talk about current events. He does read the art reviews of the New Yorker, browses the classifieds and watches American football with the sound on mute, but otherwise he has been remarkably successful in constructing a world where very little he doesn’t like gets through to him. In this regard, he might be regarded as similar to the hundreds of millions of people that get their news via Facebook, which similarly filters out numerous stories and events. His approach has shades of Thoreau’s Walden too. Previously a senior executive with Nike, Disney and Walmart, he now spends his days (and his money) restoring a disused coal mine into a pristine pond – a project he calls The Lake.

Back in November 2016, when Trump was elected President of the United States, Erik Hagerman had a plan. Distressed by the hoopla of US politics he decided to stop reading the news. His experiment was part protest, part a coping mechanism and part extreme self-care. Living alone on a pig farm in rural Ohio this was clearly achievable in ways that it might not be had he lived somewhere else like Chicago. Hagerman travels into the local town, Athens, to buy coffee and to shop, but he keeps up his news blockage with the help of white noise from his headphones and an agreement with family and friends not to talk about current events. He does read the art reviews of the New Yorker, browses the classifieds and watches American football with the sound on mute, but otherwise he has been remarkably successful in constructing a world where very little he doesn’t like gets through to him. In this regard, he might be regarded as similar to the hundreds of millions of people that get their news via Facebook, which similarly filters out numerous stories and events. His approach has shades of Thoreau’s Walden too. Previously a senior executive with Nike, Disney and Walmart, he now spends his days (and his money) restoring a disused coal mine into a pristine pond – a project he calls The Lake.

Back in 2018, I personally stopped listening to most news on the TV. I still read a few newspapers, but mostly weekend papers and I read them several weeks, if not months, late. Does this work? In my experience, it does. I’m calmer, I’m able to see connections between ideas and events better, and I can scan the paper (it has to be on paper) faster because I have the benefit of hindsight. Why not try it yourself?

The key argument in favour of autonomous vehicles, such as driverless cars, is generally that they will be safer. In short, computers make better decisions than people and less people will be killed on the world’s roads if we remove human control. Meanwhile, armed robots on the battlefield are widely seen as a very bad idea, especially if these robots are autonomous and make life or death decisions unaided by human intervention. Isn’t this a double standard? Why can we delegate life or death decisions to a car, but not to a robot in a conflict zone?

You might argue that killer robots are designed to kill people, whereas driverless cars are not, but should such a distinction matter? In reality it might be that driverless cars kill far more people by accident than killer robots, because there are so many more of these machines. If we allow driverless vehicles to make instant life of death decisions surely, we must allow the same for military robots? And why not extend the idea to armed police robots too? Same logic.

My own view is that no machine should be given the capacity to make life or death decisions involving humans. AI is smart, and getting smarter, but no AI is even close to being able to understand the complexities, nuances or contradictions that can arise in any given situation.

About Brexit, I assume?