A study by Tinna Laufey at the University of Iceland has looked at behavioral changes in Iceland since the economic crash of late 2008. It reveals that all unhealthily forms of behavior (the ones they measured anyway, like consumption of alcohol, tobacco and sugary drinks) have fallen since late 2008. People are also working less, more people are getting married and more are getting a good night’s sleep. So recession = good?

Category Archives: Uncategorized

The Future of Love

I’ve become very self-conscious following my last post about being anti-social. For example, is this new post trivial or worth posting? Is it about anything other than me? Anyway, as a link to last week’s discussion about machines demeaning human beings, I’ve just been asked to think about the future of love, which could almost be as much fun as thinking about the future of fun. Now I’m not sure why exactly I’ve wandered onto relationships and sex, but have you seen any of the material on sex robots and is it just are or I these things really creepy? As for the image above, I’m not sure about the “Rental” business, although I guess that’s no different to what some people do with themselves and to other people already. As for the second image, is that a wedding ring on the finger of the guy not quite in the picture?).

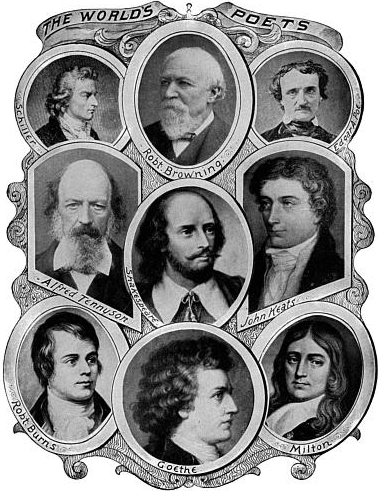

Idea of the week – poetry

A jukebox that plays poems…

This idea doesn’t actually exist yet*, so in the meantime here’s a poetry app created by Maurice Saatchi as a tribute to his late wife, Josephine Hart, which allows you to listen to great actors reading great poetry (free).

And if you really like poetry try this too – the poetry cafe

* The idea belongs to (or appears in) The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach.

Can’t write

I don’t know if it’s the cold office, the dark office, the office that moves up and down (the boat in London) or something else, but I can’t seem to write anything interesting at the moment. For some reason this brings me on to George Orwell’s Six Rules for Writing. Personally, I’d add that if you are blocked go out and see something (someone?) different. Generally do something else until the urge returns. Or visit your muse. The six rules:

1. Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

4. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Dark Solar

I seem to remember making up something called ‘Night Solar’ in one of my recent books.Turns out he idea isn’t quite as mad as it was intended to be. The cover of New Scientist (26 January) is all about Dark Solar, which appears to be much the same thing.

More Bad Language

A report by the National Organisation of University Art Schools in Australia says that schools should be teaching ‘visuacy’. The National Association for the Visual Arts (NAVA) is similarly focusing on the “outcome” of visuacy being a stand-alone subject for years K-10 and the National Review of Visual Education says visuacy should be given the same prominence as literacy and numeracy.

So what is this strange new skill that will be so fundamental to students in the 21st Century? Judging by the fact that the report cites the example of deconstructing an advertisement for Elle Macpherson’s kickers to establish “conditions of value and meaning” alongside an examination of Picasso’s Guernica, visuacy appears to mean visual literacy plus post-modernism minus a sense of humour.

Doubtless members of the Visual Education Roundtable (“a coalition of key stakeholders to be an advisory body to CMC and MCEETYA”) will paint me as a pedantic philistine, but I can live with that. Newspeak like this is a mutant life form from outer space (i.e. certain parts of Canberra, Westminster and Washington) and needs to be killed off before it infects the whole planet.

To put the record straight I’m all in favour of visual literacy. So is my mum, who used to be an art teacher. Our brave new world is saturated with images and it’s going to get much worse in the future. Everything from walls and tabletops to cereal packets and clothing will soon have the potential to become screens displaying the almost infinite amount of information and entertainment created by you, me and everyone else.

Thus we will be drowning in digital dross and there will be a real need to filter this material, either by visualising information or by understanding the difference between stylish eye candy and items of real substance.

But according to post-modernist academics with a love of Jerry built jargon all of this imagery is of equal value. A video by Kylie is as meaningful as a painting Van Gogh. We should be so lucky. My point here is not a discussion about postmodernism. What’s getting my goat is simply the use of bad language, especially in schools. Yes we live in a visually cluttered culture, but that doesn’t mean that words don’t matter.

Not Thinking

This is a classic. I was on my way to an event in London this morning when I found myself on an escalator behind a woman in her mid-forties. She was wearing a perfume, which reminded me of someone that I last saw about fifteen years ago. So, without thinking about it, I leaned forward and sniffed. Unfortunately, it was quite a loud sniff, which may or may not have been accompanied by an even larger sigh. The woman quickly turned around and loudly asked: “What are you doing?”

My response was honest, although possibly not that well thought out. I simply responded: “I was sniffing you.” Never, in the history of transport have so many people given any individual quite so much room quite so fast. In the future I will sniff quietly. BTW, that’s not her in the picture.

Thinking…

Been having lunch with a couple of the the scenarios team at Shell. Interesting discussion, amongst other things about whether demand for energy could fall in the future due to dematerialization (links with a previous blog post about the story I saw in the US about electricity demand being essentially static, which seems counter-intuitive). Anyway, Shell’s new set of scenarios will be out quite soon.

The image is of a park bench on the South Bank. I was a bit early for lunch so spent 15-minutes wandering around and looking at stuff.

Brain Grenades

The last truly great essay I found online was years ago and it was “Why the future doesn’t need us” by Bill Joy, but several people have now mentioned this one, which I stumbled upon myself a while back. It’s by Nick Bostrom, a philosopher at Oxford, and it’s called “Are you living in a computer simulation?” He argues, and I more or less quote, that at least one of the following thoughts are true.

1) The human species is likely to become extinct long before reaching a “post-human” stage. 2) Any post-human civilization is unlikely to run simulations of their evolutionary history. 3) We are almost certainly living in a computer simulation. All very The Matrix.

Quote of the week

“You have to have an idea of what you are going to do, but it should be a vague idea.” – Picasso