One of the concerns relating to an increasingly elderly population is how people will move around, especially if you are trying to encourage physical interaction and avoid loneliness. Exoskeletons are one solution. Self-driving personal mobility pods are another.

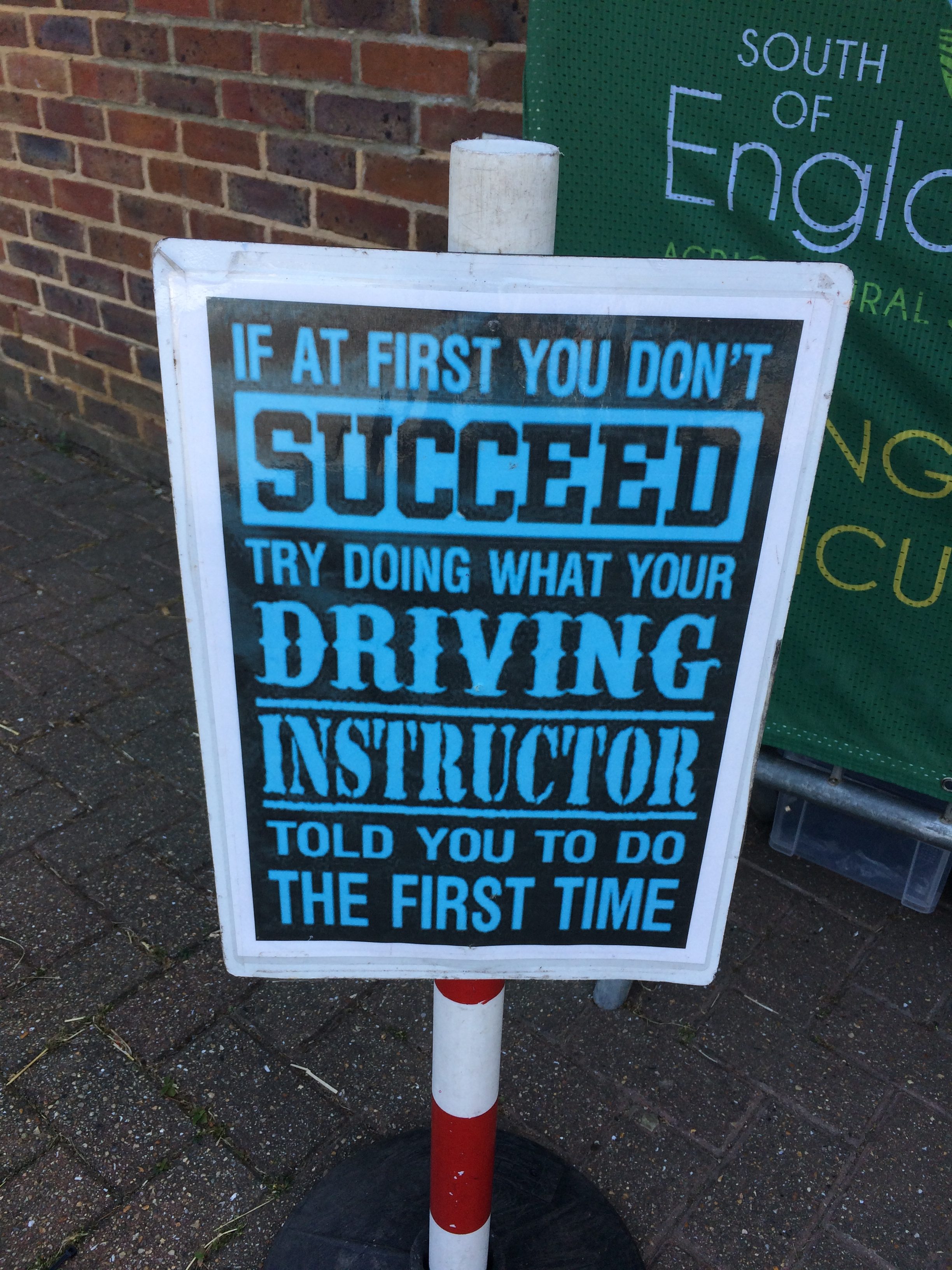

Google’s self-driving cars have driven several million kilometres, with only a handfull of minor incidents, all of which were the fault of humans. It seems driverless cars run into a problem: humans that don’t follow rules.

I can sympathise with the humans. I have a fondness for older cars. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that I’ve ever fallen in love with one, but I’ve come close. Like avatar children, cars can be designed to appeal to a set of very primitive emotions. How some curved sheets of steel from the 1970s can inspire joyous feelings is illogical. Perhaps it’s Freudian. Perhaps it’s my mother. Maybe it’s those womb-like curves. More likely though, it’s a designer working in an era before computer-aided design, which according to Nicholas Carr, ‘bypasses much of the reflective and exploratory playfulness’.

Modern automobiles are safer and in some ways more efficient, yet they’ve lost much of their soul. Contrast a sensual 1966 Lamborghini Miura (designed by a 22-year-old with no computer) or a hypnotic 1973 Ferrari Daytona (designed on paper in seven days) to their modern equivalents.

Modern cars fill me with frustration in other ways, too. Freeman Thomas, a designer at Ford, says that technology is ruining the driving experience. I’d agree. I have a friend, David, who owns a 1958 Alfa Romeo Giulietta, but also a modern Porsche 911. He says he gets more fun out of the Alfa at 60 km/h than the 911 at full throttle. But I have better examples of how rapid movement isn’t necessarily synonymous with progress.

The first was when I lost a spare electronic key to a modern Land Rover. The key eventually showed up, yet not before I’d visited a sales representative who informed me that a new computerised key would cost £110, plus tax, plus a further £60 to program it. Surely this is intermediate technology? It’s not as good as a metal key, which is almost impossible to damage and can be cut for next to nothing, nor as good as an i- key, which you can locate with your phone, tablet, or laptop when it gets lost.

Or there was the time the Land Rover broke down and I got a loan car for a few days. I spent a frustrating 15 minutes sitting in the driver’s seat trying to work out how to start the car. The problem was there wasn’t a slot to put the computerised key into as there was on my older Land Rover. Apparently, the key merely needed to be in the car, but the car had to be in park and my foot needed to be on the brake, too.

An even better example of how complexity can be synonymous with stupidity concerns a Subaru. A friend of my wife drove over not so long ago to drop her child off. She didn’t want to stop, but she was persuaded to turn the engine off and have a quick cup of tea. Little did she know, there wasn’t a key in the car. It turns out that you can start some cars if the key is near enough to the car — and you can even drive away. The only thing you mustn’t do is switch the engine off, because then you can’t start it again. Has the automotive world gone completely mad? Back in the day, I could start any car if it broke down. Now if a car won’t start, it’s me that breaks down.

The number of cars on the world’s roads is set to double in the near future. This has consequences for natural resources and climate — and human safety. In an average month, 108,000 people around the world die in car accidents, and this figure is forecast to rise to 150,000 by 2020. In 90 per cent of cases, car accidents are caused by human error rather than machine failure, and with ageing populations this could become worse.

A US study, for instance, found that while over-70s were 9 per cent of the US population, they were at fault in 14 per cent of all traffic accidents and were responsible for 17 per cent of pedestrian deaths. Clearly, removing humans, especially older ones, from the driving seat would, in theory, be a good idea. It could make traffic flows more efficient and reduce pollution, too. We already accept the idea of traffic being managed remotely, so why not send data to the cars themselves and have the cars work out what to do?

Yet there are ethical problems surrounding such automation. As Nicholas Carr observes, ‘At some point, automation reaches a critical mass. It begins to shape societies norms, assumptions, and ethics.’ For example, would it be right to outsource life and death decisions away from drivers and place them in the hands of proprietary algorithms? Could you, should you, program a machine to make moral judgements? How would you feel about a car that calculated that it was worth driving into a tree and killing you in order to save the lives of two drunken strangers running across the road? (BTW, I’ve been driving for 40 years and never once have I encoutered such an ethical problem).

We’ve had machines making judgements about drivers for years, although we rarely notice. Automatic license-plate recognition systems have been operating since the mid-1970s and have become common since the 1980s. Cameras monitoring bus lanes and speeding are equally ubiquitous. In the Netherlands and Australia, fines are even regularly sent out with no human oversight or intervention whatsoever. Developments such as these bring the ability to monitor and punish human behaviour on an unprecedented scale.

For example, it’s already possible to install cameras to catch public drunkenness. Algorithms analyse body movement or body temperature and blood flow to the face. This has shades of Kafka. And what happens to a culture when even the most minor infringement is enforced and where human intervention, human discretion, and human appeal are not available? For algorithms, everything is a binary decision.

One possible result of this and other developments could be a citizenry that is more cautious and contrite. It’s also possible we could see a society that’s less autonomous and experimental and less likely to voice opposition to the government, the police, and popular opinion.

Essentially, there are two broad solutions to making cars safer and taking the chore of driving away from the driver. One is smart cars; the other is smart roads. The idea of putting tracks or wires into roads to steer cars — a cross between dodgems, trams, and Scalextric — has been around since the 1950s and could work perfectly well, except that we currently struggle to even stump up the cash to fix potholes. Making roads super-smart and keeping them clever, while constantly digging them up for repairs, might be too difficult.

The other option is to make cars so smart that they can drive around by themselves unaided. The technology to do this pretty much exists. Do you really think Google Maps was designed for humans? I think that’s about as likely as Google’s book- digitisation project being designed for people. Both, in my view, have been designed for machines from the very beginning. If you join up Google search, with Google navigation, Google cars, and perhaps Google genomics, the future could be a little disturbing.

Driverless cars should become commonplace in major cities in ten or 15 years, although the technology will likely be introduced in phases. For example, many cars already feature emergency auto-braking, while cruise control systems are being extended to allows hands-free driving both on freeways and in slow urban traffic. You can bet that manufacturers are also looking at other ways of removing control from a driver for their convenience or safety.

Once cars start to drive themselves, they will most probably park by themselves, too, or simply continue to drive around looking for another ride if the vehicle is shared or communal — a bit like an ordinary taxi. And if drivers no longer need to drive, they would be free (and safe) to do other things, such as work, eat, drink alcohol, read newspapers, watch movies, or look at funny videos of cats. Given that Google’s business model is built around advertising, maybe we’ll be watching ads in our cars in return for a ride.

Or if roadside distractions are no longer a problem, maybe we’ll see arrays of moving screens alongside roads. Or Google Pods and Dyson e-Cars will personalise every windscreen so that what I see in front of me is not the same as what you see.Most interesting though is what happens when fully autonomous electric cars become the norm, especially in cities. This will focus attention on car design (less need for dashboards and controls) and urban planning (as easier long commutes may mean larger cities, while increased traffic efficiency may lead to higher density). Widespread adoption of autonomous cars could even negate the need for traffic lights and road signs — pedestrians would then need augmented-reality glasses or a mobile device to find their way around. And if millions, or even billions, of electric cars become standard and battery technology improves, there’s the awesome option of creating fluid local energy-storage networks, or grids, where power can be physically moved from one place to another.

How people buy and finance cars could change as well. Ultimately, we may abandon the whole idea of owning and driving our own vehicles. Instead, we might subscribe to one — or many, as some people already do. We might summon a communal vehicle with a tap of a smart device, and leave it anywhere we like when we no longer need it.

Our cars may never run out of fuel, either, due to inductive charging. Rather than finding a power socket and uncoiling a length of cable, you could drive the vehicle onto a plate or coil embedded in the surface of the road. Electromagnetic induction will then charge the vehicle wirelessly. What’s new here is that scientists have developed a way to do this with an energy-transfer efficiency of about 90 per cent. You could totally charge your vehicle while parked in a garage, car park, or shopping centre, or you could extend its range by topping up the batteries en route.

However, history and associated cultural norms can take a long time to change, especially when associated with totemic objects. Moreover, when we no longer need to drive cars, we may find we’d rather like to. Driving for sheer pleasure, as opposed to practical mobility, may return — and the automotive industry will have come full circle. Surrendering control to a robot in the form of a vehicle may prove too much for some people, especially if the car locks you in when it starts, or completely removes the steering wheel and the option of human control. Chances are, it will only be a matter of time before a major city bans human driving, but if self-driving cars start to kill humans in large numbers there could be a sudden and unexpected change of direction. As for turning cars into places of work and social connection, we might find this is precisely what we wish to avoid. A car remains one of the last private spaces, and the intrusion of yet more work (or more virtual people) may be resisted. As for boredom, this can have its uses. Many an insight arose from a boring car journey.

But from an economic efficiency standpoint, self-driving cars make sense. For many people, driving is no longer a pleasure. In Los Angeles, for instance, drivers within a 15-block district drive 1.5 billion kilometres each year looking for parking spaces, which is 38 trips around the Earth, 178,000 litres of fuel, and 662,000 kilograms of CO2. Allowing people to do something else in the front seat could have its advantages. Also, hospitals would have fewer injuries to deal with and emergency rooms would be less busy.

However, technical problems remain. Human drivers, for all their stupidity, are still pretty smart. Humans can tell the difference between a plastic bag in the middle of the road and a solid object. Shadows of trees aren’t usually confused with the roadside, and it’s fairly easy to tell the difference between a child on a bicycle and a deer.

Machines, even smart ones, break down. And while we’re reasonably tolerant of computers and mobile phones not working, cars are another matter, particularly if they’re in control. A dropped mobile-phone signal or a crashed tablet is rarely a matter of life and death. Remember the Toyota recall of ten million supposedly defective cars in 2009? It was rumoured that cars were accelerating by themselves and that people had died.

Digital cars could also be targets for hackers and cyberterrorists, although the problem is more likely to be tech-savvy criminals stealing autonomous cars remotely. Having said that, there’s already been the case of Rolling Stone magazine journalist Michael Hastings. In 2013, his car drove into a palm tree at high speed and exploded, killing him. Given that Hastings had a reputation for revealing stories about the US military and intelligence services and had emailed friends the day before saying that he was working on a big story and was going ‘off the radar’ for a while, this accident looks suspicious to some.

Any modern car that uses computer software to control its engine, transmission, and braking could in theory be hacked. General Motors (OnStar) and Mercedes (mbrace), for instance, already use mobile networks to monitor key components, and even the cheapest cars can be plugged into a laptop to diagnose faults.

Sooner or later, something will go wrong. Perhaps that’s why, in a poll, 48 per cent of people in the UK would be unwilling to be driven by a self-driving car and 16 per cent were ‘horrified’ by the idea. Then again, it wasn’t so long ago that people thought that travelling by train would make them sick or even kill them.

I don’t know whether it’s better car design, or social acceptance over time, but when I was growing up lots of people were sick in cars and aeroplanes. Nowadays, this is rare. Again, one of our human traits is being adaptive, and we can get used to most things given enough time.

Overall, the biggest issue isn’t human or technological. The problem with driverless cars and automated transport generally concerns regulation, legal liability, and especially the legal reaction to unforeseen accidents. Critical to this will be the level of trust between people and machines.

So what’s next? The answer will be human caution and incremental levels of technological evolution and trust. We’ll see more driverless trains and driverless buses, and trucks could follow. The big carmakers will proceed in the direction of full autonomy, but at slow speed. Technology firms will be less cautious, yet even here any technology push will be subject to consumer pull and legislation, which will tend to obstruct, especially in risk-averse and liability-obsessed nations.

The future will therefore arrive piece by piece with the odd crash, sudden-braking incident, and multiple pile-ups. No doubt, many people will lose their jobs. That includes cabbies, truck drivers, and even much maligned parking wardens. Car-rental companies may have to rent driverless cars that offer pick-up and drop-off services, while car parks may lose their value, reducing revenue for local councils. And when self-driving cars are insured, it may be the car companies and software firms that pay, not the human occupants.

In the big picture, quite where driverless cars will take us is unclear, although we should perhaps bear in mind that interest in cars is waning generally in the developed world. The number of kilometres people drive has fallen of late, and car ownership is reaching saturation. In major cities such as New York and London, around 50 per cent of people don’t even own a car. I imagine that in the future, millions of people may grow up never having held a driving licence or a steering wheel.

While retirees still drive, young people are eschewing cars for public transport. In France, for example, people under 30 account for less than 10 per cent of customers for cars, and the average age at which people buy their first new car (as opposed to used car)

is now 55. The numbers are much the same across Europe, with the average age of Volkswagen Golf buyers being 54.

In Paris, the trend is towards public transport, carpooling, and peer-to-peer sharing. For instance, BlaBlaCar has ten million members in 13 European countries, including France, and Autolib has 170,000 subscribers in Paris alone. One market- research firm suggests the French see cars as a ‘clumsy assertion of social status’, as well as a tangible sign of social inequality.

Thanks to the internet, younger generations can do a lot of their travelling via the screen, and it is mobile devices that have become symbols of identity and freedom. In developing regions, mobile phones are similarly an alternative to poor roads and expensive transport.

Then again, arguing that the era of personal car ownership is over, especially because people just want to move efficiently from point A to point B, could be making the same mistake as arguing that watches are dead because people have clocks on their phones. This argument goes back to the 1970s, when digital watches first appeared. People said that expensive watches would fade away. They didn’t, because people don’t only use watches to tell the time. They are fashion items, statements of identity and status, and the same might be said for private cars.

But before self-driving cars become a self-fulfilling prophecy, there’s a more dangerous idea coming down the road. The EU has decreed that all new cars sold in Europe be fitted with connectivity, most probably in the form of a SIM card, so cars can automatically call for help in the case of an accident. In theory, such connectivity would also allow cars to contact breakdown services in case of mechanical failure. This is an excellent idea and surely one that will be music to the ears of companies such as Apple and Google, who have recently launched CarPlay and Android Auto. A survey by McKinsey has found 27 per cent of iPhone users would swap car brands if a rival offered better in-car connectivity. Connectivity could be used to access real-time traffic data, find vacant parking spaces, or stream music services (a subscription service called Rara already offers in-car access to 28 million songs).

Putting ordinary cars online means that other things become possible, too. Apart from local traffic and incident reports, you could see what a car a kilometre in front of you is looking at. My son says that you could also get advance warning alerts of cyclists in front of you or that you could pay the slow-moving car in front of you to move out of the way. As in other areas of insurance, car insurance companies have traditionally relied on demographic data (usually filled in by customers) to calculate premiums. Age, sex, occupation, and location are ranked alongside car type and engine size. Now, new technology is shifting the market towards personalised policies, based on digital sensors embedded within vehicles and on how a car is driven. This allows insurance companies to weed out higher-risk drivers and offer discounts to safer drivers. In the US, premiums are moving toward a distance-driven model, while in Europe premiums are being focused on how people drive.

Monitoring is generally done by telematics — the use of black boxes to send data to the insurance company or to apps on drivers’ phones. Such surveillance can also alert insurance companies to insurance scams, especially when sensors are used in conjunction with forward-facing dashboard cameras such as those commonly used in Russia. However, used in conjunction with Big Data, we may create a situation where people are penalised financially for propensities rather than actions. Algorithms could suggest that someone is high risk and they would be punished without them doing anything, although you might argue this happens already.

The biggest orderly rollout of forward-facing cameras has been by police around the world. In the UK, around 5,000 body cameras alone are now being worn. The main lesson learned is that awareness of these cameras tends to modify the behaviour of both the officers and those they interact with. With increasingly watchful insurers, we might expect to see safer driving even before machines take the wheel. So what’s the bad news?

Automotive and technology companies have thus begun selling us a vision of the future where we can drive and still be fully connected. Hands-free phones are standard, but the latest temptation is sending and receiving texts without looking at a screen or using your hands. Some high-end cars even allow drivers to book restaurants and theatre tickets without (in theory) moving their gaze from the road ahead. According to McKinsey, by 2020 around 25 per cent of cars will be online. This is all a terrifically stupid idea.

In 2011, distracted drivers killed 3,300 people in the US, and in 2013 US authorities recommended that the display of text messages or web content be banned in cars. Numerous studies have highlighted the severity of the problem, including a 2002 UK study by the Transport Research Laboratory, which found that drivers using hands- free phones reacted more slowly to events than drivers who were slightly above the alcohol limit. In 2005, an Australian study reported drivers using hands-free devices were four times more likely to crash than drivers focused solely on the road. Lastly, a 2008 US study found talking on a hands-free phone was more distracting for the driver than talking to a passenger, a finding echoed in a 2015 study by the RAC Foundation in the UK.

The current legal assumption is that if people don’t take their eyes off the road when using these devices (which they do), it is safer — yet it doesn’t make it totally safe. The problem is not removing human hands, but dividing attention. Human attention is finite, and multi-tasking splits mental resources.

A study by the University of Sussex in the UK found that digital multi-tasking (in this case, ‘second screening’) created a change in the anterior cingulate cortex, impairing decision-making and impulse control. Another study found links between high levels of multi-tasking and weak attention, so the signs aren’t good. You might be able to drive and glance at a screen, but what happens when something unexpectedly happens in front of you?

In the era of satellite navigation, there is technically no longer a need to know where you’re going. Or is there? What if space weather (e.g. solar flares) temporarily knocks out Earth-based GPS systems? GPS and digital maps are great, but surely an appreciation of how to get to where you’re going without them is useful.Paper maps literally give you the bigger picture and educate us about space and context, too. Evidence is even emerging that the situational awareness provided by paper maps may be good for our brains. According to Veronique Bohbot from McGill University in Montreal, the use of digital maps could be putting us at risk from dementia, on the basis that if we don’t use certain parts of our brains — parts linked to spatial awareness and memory — we may lose them.

This prompts the question of whether our brains might become less expansive or reflective if we stop driving. We coped perfectly well, it seems, before the invention of the motorcar, although a study by University College London did find that the brains of taxi drivers completing ‘the Knowledge’ training can change structure due to external stimulation.

Cabbies typically spend up to 70 weeks learning 320 journeys in the official training book so they know the entire Knowledge zone in a ten-kilometre radius of Charing Cross. They have to memorise 25,000 streets and 20,000 landmarks. With a dropout rate of 70 per cent, this is a gruelling task. The drivers claim technology can never compensate for their superior Knowledge, nor can it cope with sudden changes in the city, such as road closures.

One happened to me only recently, when The Mall in London was briefly closed just as we (and the Queen) approached it. The driver was able to deftly reroute us. The Knowledge contains the facts of the city, such as bridges and one-way streets, but taxi drivers also deal with the humanity of the city, too — on the spot, as only humans can.

As an aside, a separate concern with Google Maps is that that what you see isn’t always what everyone gets. In 2013, the company launched a version of Google Maps in which the representation of a city is different for each individual depending on what Google knows about the user. This doesn’t mean you’ll get lost, but it does mean that highlighted items of interest could change. Is this another example of Google filtering out serendipity in favour of insularity, as Nicholas Carr suggests?

Finally, while driverless cars may not threaten the jobs of all taxi drivers in big cities, they will almost certainly mean fewer jobs. Driving cars and trucks is a useful job if you don’t have any qualifications. As The Economist magazine has pointed out, when the horseless carriage replaced horse-drawn transport, the economic gains were ‘broadly shared by workers, consumers and owners of capital’. The car was a ‘labour augmenting’ technology, which means that it allowed people to serve more customers at faster speeds over greater distances. But with driverless cars, and automation generally, the gains are less equal.

When are we going to learn the value of experience, wisdom, and spontaneity, and when is society going to evaluate any benefits — cheaper and more efficient for some — against overall costs in the broadest sense for many?