It breaks my heart, but sometimes you just have to kill an idea you’ve been working on for ages. Seems this book idea is dead. But there’ll be another one along shortly….

This book is a gentle plea for a different kind of thinking. Specifically, it’s an appeal for a calmer, slower, deeper and far more reflective mind-set, which I firmly believe is necessary if one wishes to escape from the humdrum and enter the extraordinary.

Calling this essay How to Think could be problematic. Do people really want to be told how to think? Surely thinking is an intuitive skill that doesn’t need thinking about? This is partly true, but on another level thinking requires conscious and deliberate effort.

Have you ever really thought about this?

We aren’t generally taught how to think at school and we don’t think about our thinking much thereafter. This is a great shame, because our thinking, especially our imagination, is perhaps the most precious natural resource we’ve got on earth. But it’s one that’s being polluted by endless streams of digital interruption and chocked by the narrow nature of education and the short-termism of politics and business. Our liberty to think openly and freely is also being eroded by universities supporting ‘no platform’ policies and by the visceral hatred endemic in so much contemporary debate.

This hasn’t always been the case, and it’s not true everywhere either. But our fixation with doing many things as quickly as possible at the lowest possible cost is making us, our institutions and society infirm. Even weekends and holidays, which were once times for relaxation and reflection, have been invaded by devices that demand our constant attention and disconnect us from our true selves. I might be wrong, but the collateral damage of our hyper-connected world might be that we are becoming less connected, both to ourselves, others, and the wider world. Our mental focus, like our education system, is shrinking when it should be expanding. We need to bring back breadth, depth, reflection and, above all, relentless curiosity.

Numerous people have written about the neuroscience of thinking, especially how our sly subconscious gets us into so much trouble.

We are surrounded by the debris of this on a daily basis.

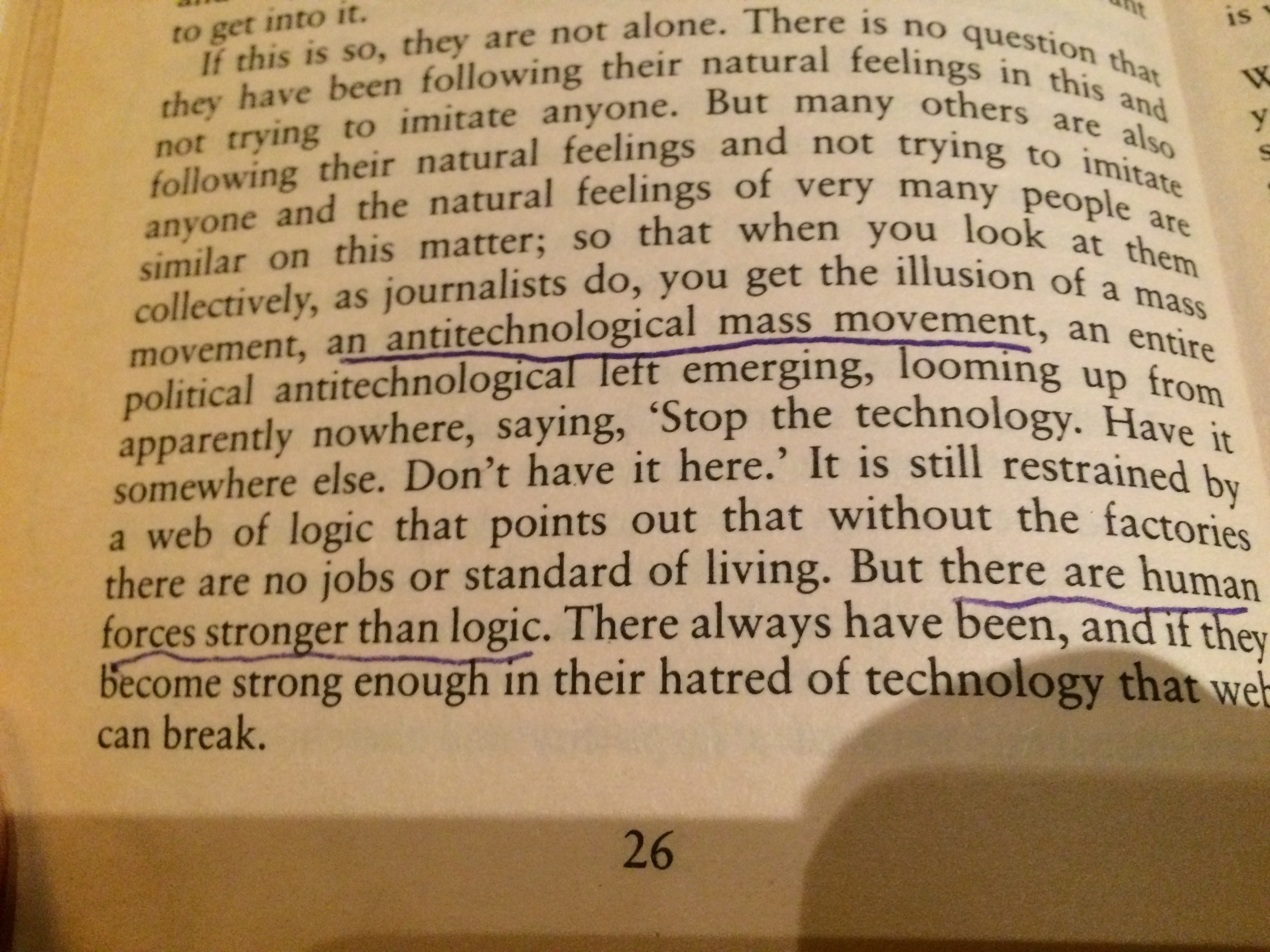

We rush into roles, responsibilities and relationships without properly thinking, or we think about such things in a singular, linear and unconnected manner. We ignore the layered lessons of history, the cyclical nature of so much change and the counter-forces that often emerge in response to significant innovations or events.

Essays about the creative process abound too, but these tend to exist within a sterile vacuum divorced from real world pressures, organisational psychologies and institutional pathologies. Have you ever tried really thinking at work? Without permission? For a whole day? Without getting reprimanded? Or what of the impact of mood on thinking? Why don’t we think about this more often? Why are we so careless with the physical environments in which we expect our co-workers to think and our children to learn? On all counts, the result is thinking that’s becoming increasingly timid, lazy, shallow, sterile and one-dimensional, which is making us open to unmanageable surprises.

I would like to address all these issues and more, but from a positive perspective. I am less concerned about why things go wrong and more interested in how to put them right. How can we manipulate our meddlesome minds to make them more attuned to new risks? How can we become more sensitive to the faint murmurs that are so often the forerunners of opportunity? How should we embolden individuals and organisations alike to filter out utter nonsense, spot valuable anomalies or simply stop for a moment and take stock of where they are and what they are doing?

Most importantly, we are potentially on the cusp of a radical revolution in artificial intelligence. How might we educate our minds – and those of our children and our children’s children – to be open, adaptive and resilient in such a potentially disruptive environment? How should we think when machines can do this for us? How can we ensure that one of the major consequences of machines that can think isn’t people that don’t or needn’t? How do we guard against a situation where complacency or disenfranchisement means we no longer ask important questions like these?

I think the answer to all this is to become very good at the things these machines are very bad at. In short, we must work tirelessly to unleash our unique ability to think conceptually, counter-factually, originally and empathetically and inspire others to do the same.

And to do this I believe we need a moderate level of disconnection and a significant amount of time. Hence, we need to reclaim solitude, silence and patience. Without this no stable sense of self can emerge. Only when we are firmly anchored in ourselves can we hold useful conversations with others from which new ideas and insights will emerge. Only when we achieve a graceful lightness of being can we float above our everyday existence and jump joyfully from the world of sterile facts – the world as it is today – to the realm of imagination and ideas – the world as it might be tomorrow.

We cannot construct a long-term strategy for accomplishment, let alone one for the survival of our species, when we are smothered by busyness and distracted by ephemera. So, sit down, turn off your devices, un-divide your attention and come with me for a gentle stroll down some overgrown paths of possibility.