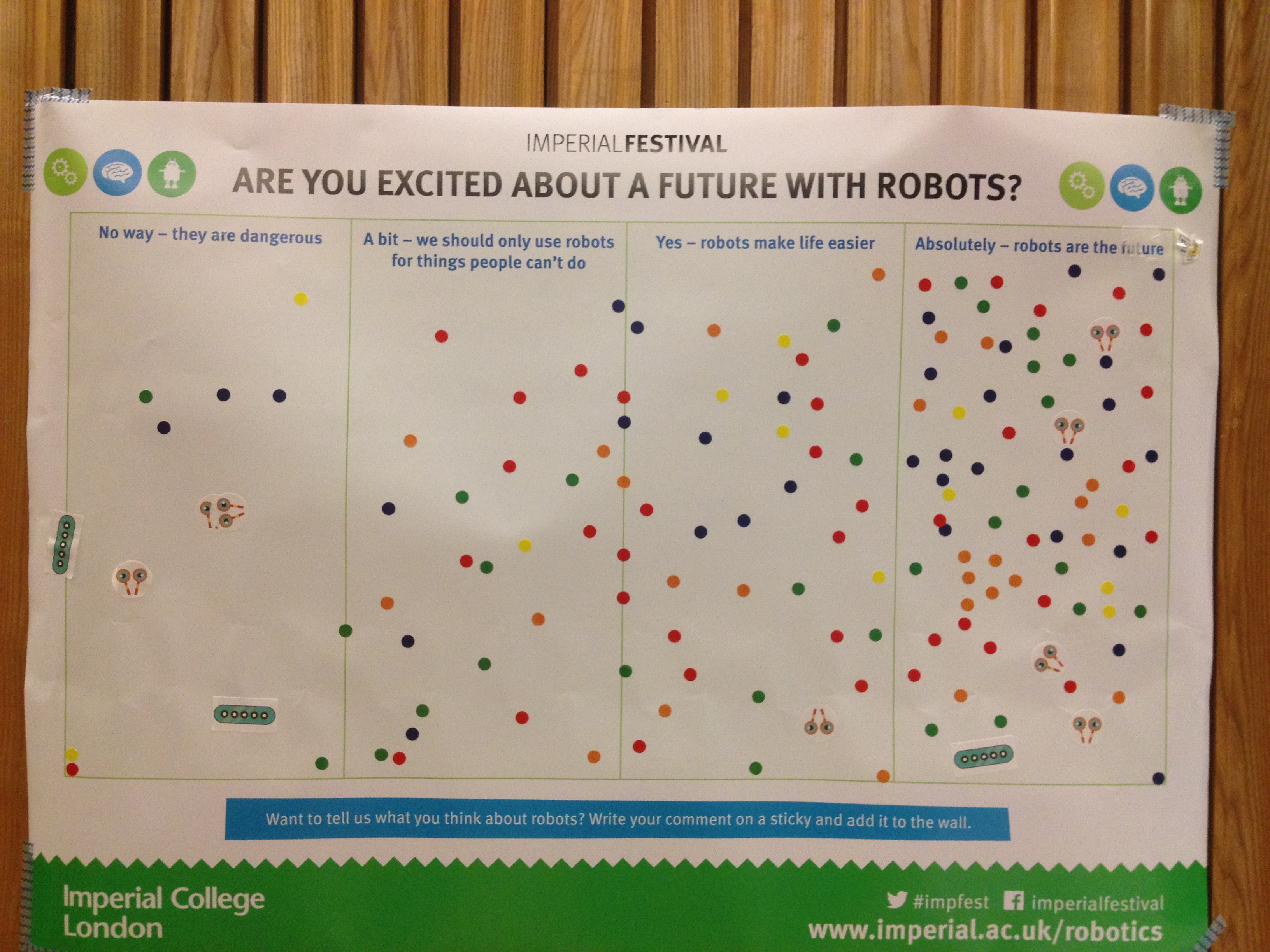

A recent bank of England Study has said that 15 million of the UKs 30 million jobs could be at risk from automation over the coming years. Meanwhile, a US PEW study found that two-thirds of Americans believe that in 50 years time, robots and computers will “probably” or “definitely” be performing most of the work currently done by humans. However, 80 per cent also believe that their own profession will “definitely” or “probably” be safe.

Putting to one side the obvious inconsistency, how might we ensure that our jobs, and those of our children, are safe in the future? Are there any particular professions, skills or behaviours that will ensure that we remain gainfully employed until we decide that we no longer want to be? Indeed, is there anything of significance that we do that artificial intelligence can’t? And how might education be upgraded to ensure peak employability in the future? Finally, how realistic are doomsday forecast that robotics and automation will destroy countless millions of jobs?

To answer all of these questions we should first delve into what it is that robots, artificial intelligence, automated systems and computers generally do today and then speculate in an informed manner about what they might be capable of in distant tomorrows.

A robot is generally defined as an artificial or automated agent that’s programmed to complete a series of rule-based tasks. Originally robots were used for dangerous or unskilled jobs, but they are increasingly used to replace people when people are absent, expensive or in short supply. This is broadly true with automated systems as well. They are programmed to acquire data, make decisions, complete tasks or solve problems based upon pre-set rules. Not surprisingly, machines such as these are tailor made for repetitive tasks such as industrial manufacturing or for beating humans at rule-based games such as chess or Go. They can be taught to drive cars, which is another rule-based activity, although self-driving cars do run into one big problem, which is humans that don’t follow the same logical rules.

The key phrase here is rule-based. Robots, computers and automated systems have to be programmed by humans with certain endpoints or outcomes in mind. At least that’s been true historically. Machine learning now means that machines can be left to invent their own rules based on observed patterns. In other words, machines can now learn from their own experience much like humans do. In the future it’s even possible that robots, AIs and other technologies will be released into ‘the wild’ and begin to learn for themselves through human interaction and direct experience of their environment, much in the same way that we do.

Having said this, at the moment it’s tricky for a robot to make you cup of tea let alone bring it upstairs and persuade you to drink it if you’re not thirsty. Specialist (niche) robots are one thing, but a universally useful (general) robot is that has an engaging personality, which humans feel happy to converse with, is something else.

And let’s not forget that much of this ‘future’ technology, especially automation, is already here but that we choose not to use it. For example, airplanes don’t need pilots. They already fly themselves, but would you get on a crewless airplane? Or how about robotic surgery? This too exists and it’s very good. But how would you feel about being put to sleep and then being operated on with no human oversight whatsoever? It’s not going to happen. We have a strong psychological need to deal with humans in some situations and technology should always be considered alongside psychology.

That’s the good news. No robot is about to steal your job, especially if it’s a skilled or professional job that’s people-centric. Much the same can be said of AI and automated systems generally. Despite what you might read in the newspapers (still largely written by humans despite the appearance of story-writing robots) many jobs are highly nuanced and intuitive, which makes coding difficult. Many if not most jobs also involve dealing with people on some level and people can be illogical, emotional and just plain stupid.

This means that a great many jobs are hard to fully automate or digitalise. Any job that can be subtly different each time it’s done (e.g. plumbing) or requires a certain level of aesthetic appreciation or lateral thought is hard to automate too.Robots, AIs and automated systems can’t invent and don’t empathise either. This probably means that most nurses, doctors, teachers, lawyers and detectives are not about to be made redundant. You can program machines to diagnose illness or conduct surgery. You can get robots to teach kids maths. You can even create algorithms to review case law or predict crime. But it’s far more difficult for machines to persuade people that certain decisions need to be made or that certain courses of action should be followed.

Being rule-based, pattern-based or at least logic-based, machines can copy but they aren’t capable of original thought, especially thoughts that speak to what it means to be human. We’ve already had a computer that’s studied Rembrandt and created a ‘new’ Rembrandt painting that could fool an expert. But that’s not the same as studying art history and subsequently inventing cubism. This requires rule breaking not pattern recognition.

Similarly, it’s one thing to teach a machine to write poetry or compose music, but it’s entirely another thing to write poetry or music that connects with people on an emotional level and speaks to their experience of being human. Machines can know nothing about the human experience and while they can be taught to know what something is they can’t be taught to know what something feels like from a human perspective.

There is some bad news though. Quite a bit in fact. An enormous number of current jobs, especially low-skilled jobs, require none of these things. If your job is rigidly rule based, repetitive or depends upon the application of knowledge based upon fixed conventions then it’s ripe for digital disruption. So is any job that consists of inputting data into a computer. This probably sounds like low-level data entry jobs, which it is, but it’s also potentially vast numbers of administration, clerical and production jobs.

Whether you should be optimistic or pessimistic about all this really depends upon two things. Firstly, do you like dealing with people and secondly, do you believe that people should be in charge. Last time I looked humans were still designing these systems and were still in charge. So it’s still our decision whether or not technology will displace millions of people or not.

Some further bad news though is that while machines, and especially robots, avatars and chatbots, are currently not especially empathetic or personable right now they could become much more so in the future. Such empathy would, of course, be simulated, but perhaps this won’t matter to people. Paro, a furry seal cub that’s actually a robot used in place of people with dementia in aged-care homes, appears to work rather well, as does PaPeRo, a childcare and early learning robot used to teach language in kindergartens. You might argue that elderly people with dementia and kindergarten kids aren’t the most discerning of users, but maybe not. Maybe humans really will prefer the company of machines to other people in the not too distant future.

Of course, this is all a little bit linear. Yes, robots are reliable and relatively inexpensive compared to people, but people can go on strike and governments can intervene to ensure that certain industries or professions are protected. An idle population, especially an educated one, can cause trouble too and no government would surely allow such large-scale disruption unless they knew that new jobs (hopefully less boring jobs) would be created.

Another point that’s widely overlooked is that demographic trends suggest that workforces around the world will shrink, due to declining fertility. So unless there is a significant degree of workplace automation the biggest problem we might face in the future is finding and retaining enough talented people, not worrying about mass unemployment. In this scenario robots won’t be replacing or competing with anyone directly, but will simply be taking up the slack where humans are absent or otherwise unobtainable.

But back to the exam question. Let’s assume, for a moment, that AI and robotics really do disrupt employment on a vast scale and vast numbers of people are thrown out of work. In this case, which professions are the safest and how might you ensure that it’s someone else’s job that’s eaten by robots and not yours?

The science fiction writer Isaac Asimov said that: “The lucky few who can be involved in creative work of any sort will be the true elite of mankind, for they alone will do more than serve a machine.” This sounds like poets, painters and musicians, but it’s also scientists, engineers, lawyers, doctors, architects, designers and anyone else that works with fluid problems and seeks original solutions. Equally safe should be anyone working with ideas that need to be sold to other people. People that are personable and persuasive will remain highly sought as will those will the ability to motivate people using narratives instead of numbers. This means managers, but also dreamers, makers and inventors.

In terms of professions, this is a much harder question to answer, not least because some of the safest jobs could be the new ones yet to be thrown up by developments in computing, robotics, digitalisation and virtualization. Nevertheless, it’s highly unlikely that humans will stop having interpersonal and social needs, and even more unlikely that the delivery of all these needs will be within the reach of even the most flexible robots or autonomous systems. Obviously the designers of robots, computers and other machines should be safe, although it’s not impossible that these machines will one day start to design themselves. The most desirable outcome, and it’s also the most likely in my view, is that we will learn to work alongside these machines, not against them. We will design machines that find it easy to do the things we find tiresome, hard or repetitive and they will use us to invent the questions that we want our machines to answer.

As for how people can simultaneously believe that robots and computers will “probably” or “definitely” be performing most of the jobs in the future, while believing that their own jobs will remain safe, this is probably because humans have two other things that machines do not. Humans have hope and they can hustle too. Most importantly though, at the moment we humans are in still charge and it is up to us what happens next.