Earlier this year I gave a friend some young onion plants. He sent me a picture of them recently. Instead of the monsters that they were supposed to grow into they had ended up no larger than spritely spring onions. He asked me how mine had done. Rather than telling him that they had turned into show stopping giants I said mine had hardly grown at all either. I lied to him to spare his feelings. Could an AI do that? Is that a calculation a computer might make?

I don’t think an AI can demonstrate compassion, not unless it had been told to or learned, from experience, that this was an effective response in a particular situation, in which case the action would be insincere. It would not be authentic. It would come from the head, not the heart, and therefore would not a compassionate act.

You might argue that people might not care. Or perhaps people might be incapable of telling the difference, but if that were the case where would that leave human autonomy? What might such simulated compassion, or automated kindness, say about individual identity, empowerment or free choice? If we start to trust machines with our feelings more than people where does that leave us?

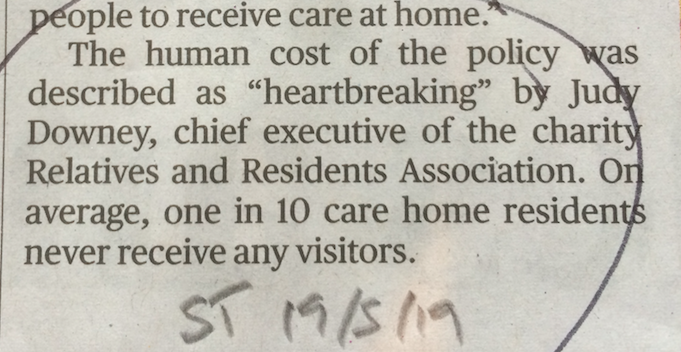

As is so often the case, parts of the future have already been distributed. Kindergarten robots in Japan are currently socialising young children, while at the other end of the age spectrum, aged-care robots are displaying synthetic affection to older people with dementia in care homes. The fact that neither of these groups have fully functioning minds adds an interesting overlay to ethical debates concerning the limits of automation (as do differing cultural interpretations of what constitutes ethical behaviour).

Personally, I think that most able-minded adults could tell the difference between true affection and affection simulated by an avatar or a robotically embodied AI.

But if human affection were for some reason missing, or unavailable, perhaps it’s better than nothing. After all, we create strong bonds with our pets, so is there much of a difference? I’d say yes, because pets are living creatures with feelings of their own. AIs don’t have true feelings and never will.

I’ll leave kindness and compassion sitting rather uncomfortably on the fence in terms of their potential for automation and turn instead to another human trait that overlaps emotional intelligence, which is common sense. Currently, a five-year-old child has far more common sense than the most advanced AI ever built. A child doesn’t need massive amounts of data in order to learn either. A child simply wanders around, exploring and interacting with its surroundings, and soon develops general knowledge, language and complex skills. Eventually, they combine broad intelligence with imagination and, if you’re lucky, a quirky curiosity about the world they inhabit. AIs do not. Even the most advanced AI today doesn’t even come close.

If you define intelligence (as opposed to intelligent behaviour) as the ability to understand the world to the point where you can make accurate predictions about various aspects of it and then use such knowledge to work out what else might be true then AI still isn’t very intelligent. Human brains endlessly update and refine themselves based upon physical interactions with the world using inputs from sensory organs. An AI might come close to doing this in a narrow area, but not to the extent that humans are able.

Despite recent developments, AI is still ruled by a mathematical logic that is devoid of any broad contextual understanding or flexibility. For example, a surgical robot might know how to do what it does, but not why it’s doing it. Frankly, the AI just doesn’t care. It would also be unaware of, and therefore unconcerned by, whatever exists outside its immediate operating environment. It is perfectly possible to extend any situational awareness and any navigational ability, but not, in my view, to the extent that humans can navigate the world. It’s one thing to design an autonomous vehicle that can ‘understand’ a complex road system, but it’s another thing entirely to design a machine that can travel around any human built (or natural) environment interacting with the almost infinite number of objects, people and ideas that may come its way. This isn’t simply because the world is highly complex, it’s because much of what happens in the world can be subtle, nuanced and confusing. The world is an interconnected system containing random elements and feedback loops, with the result that it can and does constantly change.

For humans, this isn’t too much of a problem. This is because even babies come fully equipped with a highly sophisticated sensory perception system and a reflexive learning mechanism that allows them to quickly react to changed circumstances. In fact, our ability to adapt to changed circumstances and survive in wildly different environments is possibly what marks us out from every other living species. Human intelligence is highly fluid, with the result that we are hugely adaptable and resilient. One reason for this is that our learning occurs even when we have very limited experience (what an AI might regard as limited data) or even no experience at all

Something that’s strongly related to this point is abstraction. AIs do not possess the ability to distil past experience and apply it in new situations or to radically different concepts. AIs cannot think metaphorically in terms of something being like something else. AIs cannot think in terms of abstract ideas and beliefs, which is the basis of so much human insight and invention. It’s also the source of much merriment and humour. An AI capable of writing a really funny joke? Don’t make me laugh out loud. As Viktor Frankl observed in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, “it is well known that humour, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, if only for a few seconds”. If an AI is being funny it is no more than a ventriloquist’s dummy.

Creativity, or original thinking, is often held up as an example of something we possess that AIs do not. I don’t think this is completely true. It’s perfectly possible for a machine to be creative. Alpha Go’s highly unusual 37th move during its second match against Lee Sedol in 2016 is proof enough of that. Perhaps Alpha Go’s human challenger should have recalled the words of the Dutch chess grandmaster Jan Hein Donner, who was once asked how he’d prepare for a chess match against artificial intelligence. His response was that “I would bring a hammer.” Deep Mind, the company behind Alpha Go might respond to that response by saying that this wouldn’t be fair, but this is example of how humans can think laterally as well as logically. Such originality and unpredictability is another human trait that AIs will have to deal with.

One thing I can foresee (eventually) is an AI creating an artwork that resonates with people, not because it was created by an AI, which is frankly irrelevant, but because of the beauty of the work produced. Perhaps this could be achieved by an AI studying great artworks throughout history, working out some rules for what humans find aesthetically pleasing and synthesising some original content.

A formulaic approach works for Hollywood films and popular music, so why not art? I’m not suggesting that an AI could write Citizen Kane or Gorecki’s Symphony No.3, but I’m sure an AI could generate a passable script outline or some nice melodies. This would be especially true with human help, or collaboration, which I suspect is how things will develop. The future of AI is not binary. It is not humans Vs. AI, but humans + AI.

It may even be possible, but I highly doubt it, for an AI to propose a new artistic paradigm, such as Cubism, which would rely on pattern breaking rather than pattern recognition, but to what end? Such a move would only matter is we, as humans, decided it did. Art exists within a cultural construct in which humans collectively agree what has meaning or consequence, but I don’t expect an AI would be able to understand that anytime soon either.

For me great art can be a number of things. It can bring joy, by being a beautiful representation of something we agree collectively is important, it can be provocative, or revealing, in terms of addressing a deep issue, or an important question, or it can be something that speaks to the human condition. How can an AI speak to the human condition when it is not, and never will be, human? An AI can never have any real understanding human realities such as birth and death, nor the hunger, lust, joy, fear and jealousy that surround so many human impulses and colours so much human activity.

Again, you might argue that this simply isn’t true. All it would require for an AI to address such philosophical questions would be enough data and a program. But what would the data consist of and what might the programme be designed to do? What exactly is the problem when it comes to the human condition?

Human existence is not a logical problem. Moreover, the question would surely be different each time it was asked, because we are all different versions of the same thing. Every human mind is personalised based upon individual experience. Not only are no two human minds the same, no two individuals are even changed in the same way by the same experience. How do you code for that beyond reducing everything to averages and shallow approximations?

In short, an AI can never know what it feels like to be me because it isn’t and never will be me. AIs are cold calculating machines incapable of summing up the human experience let alone my own experience. There is no ‘I’ in AI and never will be. Not unless someone works out what consciousness is and is able to replicate it artificially and I doubt that this will happen this side of eternity.

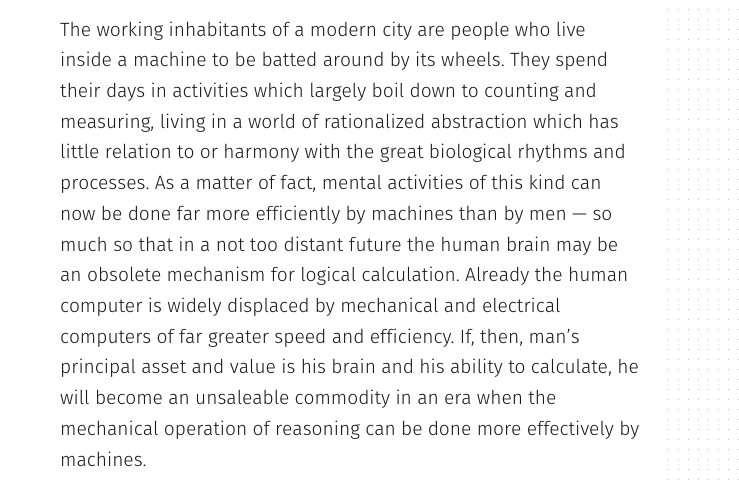

For me, the fundamental flaw in the argument than an AI can do pretty much anything a human can do (eventually) stems from the idea that the human brain is similar to, or just like, a computer. It’s not. It’s not even close. Let’s be really clear about this. Computers store, retrieve and process information based upon pattern recognition and rules. We do not. We directly interact with the real world. Computers react to symbolic representations of it, which is an important difference. This comes back to computers not really knowing about anything including themselves. Does this matter? I think it matters a great deal.

It’s true that humans make conscious calculations about things all the time, but while such calculations are often rational, or logical, many times they are not. Moreover, our irrationality can extend well beyond the real world. Humans have Gods. AIs do not. AIs do not seek meaning beyond mathematical logic, patterns or rules, while we seek ideologies and ideas to help us explain our short existence. We even anthropomorphise inanimate objects giving them inner spirits and ghosts. No AI would think of that. No AI would give consideration to spiritual matters.

We are more than heads too. We have whole body intelligence. We sense and react to things in many different ways, often in ways that are unknown to us. One of the issues with AI to date has been a focus on logical-mathematical intelligence. This has now broadened to include linguistic, spatial, body-kinaesthetic and intrapersonal intelligence, but these are much harder domains to crack. People can and do talk to each other in ways that a machine can find it easy to copy. But real conversation requires an understanding about whom one is talking to and constant assessments about that person’s interests, feelings, experience and intentions. Real conversation critically, involves some level of genuine empathy and curiosity about that person too. How can you teach an AI to be curious beyond coding it to ask a series of rather simplistic questions? Not all communication is verbal either, so you need to account for that too, which AI can do up to a point. But curiosity is based upon something else, which is a burning desire to know and understand the world and I’ve no idea how you’d code that. Yes, there’s reinforcement learning, which was used by AlphaGo, but how such learning might work alongside some human behaviours is unclear.

In short, human intelligence is a complex, nuanced and multi-faceted thing and to be of equal stature an AI would have to develop deep capability across a multitude of areas. Copying, or reverse engineering, the human brain is also easier said than done given that we know so little about how the human brain, let alone the human mind, works. Saying that in a decade or two we’ll have machines surpassing human levels of intelligence displays a profound ignorance concerning the complexity of the human mind.

Take a simple thing like human memory. We have next to no idea how this works and it could take another century for us to even come close. This isn’t to say that brains can only be made biologically, but one suspects that making one otherwise could be a lot harder than some over caffeinated commentators think.

Then, of course, there’s the idea that many of the things that are hugely important to humans cannot be measured in terms of numbers or data alone. How, for example, do you weigh up the relative importance of a poem Vs. a grapefruit? Where would you even start?

It’s also worth remembering that not all human knowledge is on the web or is even digitalised. We don’t even know what’s missing. Some things are not binary either. Many important questions, issues or dilemmas do not have simple yes or no answers. Some are fluid and others depend deeply on context and circumstance.

Take love. AIs are proving rather good at selecting potential partners for people, but is AI really doing anything more than increasing the search or shortening the odds? An AI can never love.

An AI can never understand what love feels like any more than it can translate the ‘knowledge’ that it is snowing outside into anything meaningful or meaningfully relate such knowledge to a remembrance of things past. And what of lost love? An AI can be punished, or rewarded, but ultimately an AI can never understand the fragility of our existence or what loss can feel like.

An AI can recognise or sense pain, but cannot physically feel in the way that we do. An AI cannot regret either, any more than it can understand and accurately assess other human emotions such as courage, justice, faith, hope, greed or envy. How, for example, might an AI respond to a question like “should I leave Sarah for Jane?” Answering questions like this involves more than pattern recognition or if-then decision trees. It involves emotions, fears and dreams. Again, how do you code for that? Sure, you can make an AI aware of the emotional state of a humans (affective computing), but, in my view, any understanding will be no more than skin deep. Again, AIs can’t do broad context or understand deep history. This is another reason why I believe there will be huge developments in narrow AI, but very little progress in broad or general AI for decades.

For instance, you can program an autonomous vehicle to predict the behaviour of pedestrians, recognising if someone is drunk or about to carelessly cross the road while texting. But how do you anticipate a sudden, irrational and unprecedented desire by someone to throw themselves in front of a car driving at 50 mph, maybe because they think that it might be funny? How do you combine self-driving cars that follow rules with people that don’t? Perhaps the hardest problem for artificial intelligence will be real human stupidity.

Finally, two points. The first concerns the popular idea that an AI might one day be capable of doing more or less anything a human can do, which might include stealing human jobs in vast numbers.

Such a belief supposes no human reaction.

Humans may rebel in an anti-technological fashion or enact laws restricting what an AI is allowed to do. It wouldn’t be the first time that we’ve invented something that we collectively agree not to use or decide to limit. Or governments might decide to tax AI, with the result that further developments are constrained.

A spin-off from this thought might be another, which is that in the future we may decide that while true AI is desirable, it is neither urgent or important relative to other matters and is therefore a wasteful use of human imagination and resources.

We have many pressing problems in the world today, but machine intelligence isn’t one of them. We have climate change, poverty, wars, economic inequality, a lack of clean water and poor sanitation.

All these might be addressed using AI, but AI alone cannot solve any of them, because such issues involve politics. They involve not only the prioritisation of competing economic resources, but competing, and ever changing, policies and ideologies.

My last point simply concerns why. Why are we doing this? What purpose does radical automation, or true AI, ultimately serve? Is it related to simple arguments about economic efficiency and profit maximisation that benefit 1% of the world’s population. In general terms, that seems to be the case at the moment. Or might it be to do with ageing societies and a shortage of humans in some areas?

I’m not sure what the why is with AI. What I do think is that many of our current concerns about AI might not be about AI at all. AI is a focal point for other, much deeper, concerns about where we, as both a society and a species, are heading. The worry that AI will somehow ‘awaken’ and take over is similarly misplaced. Even if an AI did awaken, why would it occur to it to do such a thing? Without anger, fear, greed or jealousy what might be the motive? I could be wrong, but even if I am this isn’t happening anytime soon and it’s far more likely that our fears surrounding AI are merely the latest of a long historical wave of hype and hysteria.

What I do think is possible, and I guess this is inspirational in a sense, is that if AI even gets close to doing some of the remarkable things that a handful of people say is possible, this might shine a very strong spotlight on what other things we humans should focus our attention upon. Ultimately, true AI could create a conversation about what we, as a species, are for and might ignite a revolution in terms of how we view our own intelligence and how we understand each other. Counter-intuitively, a truly intelligent AI might spark an intelligence explosion in humans rather than computers, which could well be one of the best things ever to happen to humanity.

Richard Watson is Futurist-in-Residence at the Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication at Imperial College London.