Here’s a prediction. You are reading this because you believe that it’s important to have a sense of what’s coming next.

Or perhaps you believe that since disruptive events are becoming more frequent you need more warning about potential game-changers, although at the same time you’re frustrated by the unstructured nature of futures thinking.

Foresight is usually defined as the act of seeing or looking forward – or to be in some way forewarned about future events. In the context of science, it can be interpreted as an awareness of the latest discoveries and where these may lead, while in business it’s generally connected with an ability to think through longer-term opportunities and risks be these technological, geopolitical, economic, or environmental.

But how does one use foresight? What practical tools are available for individuals to stay one step ahead and to deal with potential pivots?

The answer to this depends on your state of mind.

In short, if alongside an ability to focus on the here and now you have – or can develop – a culture that’s furiously curious, intellectually promiscuous, self-doubting, and meddlesome you are likely to be far more effective at foresight than if you doggedly stick to a single idea or worldview. This is because the future is rarely a logical extension of single ideas or conditions.

Furthermore, even when it looks as though this may be so, everything from totally unexpected events, feedback loops, behavioural change, pricing, taxation, and regulation have a habit of tripping up even the best-prepared plans.

Looking both ways

In other words, when it comes to the future most people aren’t really thinking, they are just being logical based on small sets of recent data or personal experience. The future is inherently unpredictable, but this gives us a clue as to how best to deal with it. If you accept – and how can you not – that the future is uncertain, then you must accept that there will always be numerous ways in which the future could play out. Developing a prudent, practical, pluralistic mind-set that’s not narrow, self-assured, fixated, or over-invested in any singular outcome or future is therefore a wise move.

This is similar in some respects to the scientific method, which seeks new knowledge based upon the formulation, testing, and subsequent modification of a hypothesis.

Not blindly accepting conventional wisdom, being questioning and self-critical, looking for opposing forces, seeking out disagreement and above all being open to disagreements and anomalies are all ways of ensuring agility and most of all resilience in what is becoming an increasingly febrile and inconstant world.

This is all much easier said than done, of course. Homo sapiens are a pattern seeing species and two of the things we loathe are randomness and uncertainty. We are therefore drawn to forceful personalities with apparent expertise who build narrative arcs from a subjective selection of so-called facts. Critically, such narratives can force linkages between events that are unrelated or ignore important factors.

Seeking singular drivers of change or maintaining a simple positive or negative attitude toward any new scientific, technological, economic, or political development is therefore easier than constantly looking for complex interactions or erecting a barrier of scepticism about ideas that almost everyone else appears to agree upon or accept without question.

Danger: hidden assumptions

In this context a systems approach to thinking can pay dividends. In a globalised, hyper-connected world, few things exist in isolation and one of the main reasons that long-term planning can go so spectacularly wrong is the oversimplification of complex systems and relationships.

Another major factor is assumption, especially the hidden assumptions about how industries or technologies will evolve or how individuals will behave in relation to new ideas or events. The hysteria about Peak Oil might be a case in point. Putting to one side the natural assumption that we’ll need oil in the future, the amount of oil that’s available depends upon its price. If the price is high there’s more incentive to discover and extract more oil especially, as it turned out, shale oil.

A high oil price also fuels the search for alternative energy sources, but also incentivises behavioural change at both an individual and governmental level. It’s not an equal and opposite reaction, but the dynamic tensions inherent within powerful forces means that balancing forces do often appear over time.

Thus, we should always think in terms of technology plus psychology, or one factor combined with others. In this context, one should also consider wildcards. These are forces that appear out of nowhere or which blindside us because we’ve discounted their importance.

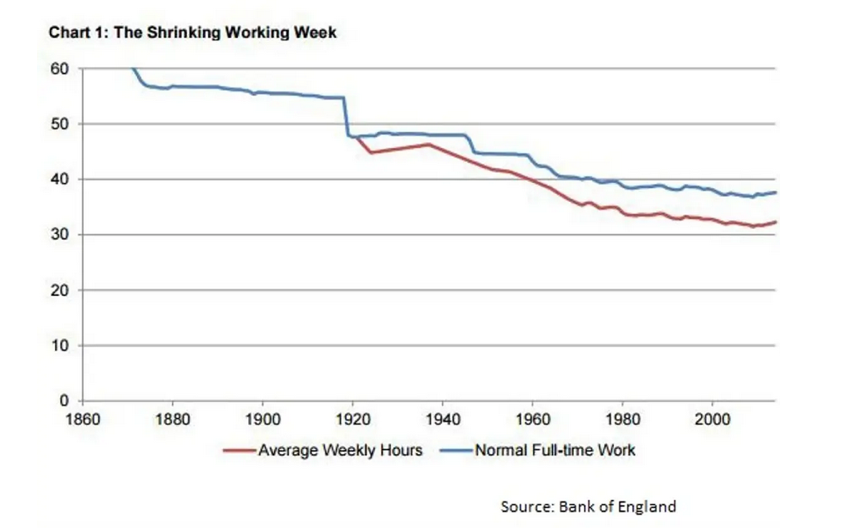

Similarly, it can often be useful to think in terms of future and past. History gives us clues about how people have behaved before and may behave again. Therefore, it’s often worth travelling backwards to explore the history of industries, products, or technologies before travelling forwards.

If hidden assumptions, the extrapolation of recent experience, and the interplay of multiple factors are three traps, cognitive biases are a fourth. The human brain is a marvellous thing, but too often tricks us into believing that something that’s personal or subjective is objective reality. For example, unless you are aware of confirmation bias it’s difficult to unmake your mind once it’s made up.

Once you have formed an idea about something – or someone – your conscious mind will seek out data to confirm your view, while your subconscious will block anything that contradicts it. This is why couples argue, why companies steadfastly refuse to evolve their strategy and why countries accidently go to war. Confirmation bias also explains why we persistently think that things we have experienced recently will continue. Similar biases mean that we stick to strategies long after they should have been abandoned (loss aversion) or fail to see things that are hidden in plain sight (inattentional blindness).

In 2013, a study in the US called the Good Judgement Project asked 20,000 people to forecast a series of geopolitical events. One of their key findings was that an understanding of these natural biases produced better predictions. An understanding of probabilities was also shown to be of benefit as was working as part of a team where a broad range of options and opinions were discussed.

You must be aware of another bias – Group Think – in this context, but if you are aware of the power of consensus you can at least work to offset its negative aspects.

Being aware of how people relate to one another also recalls the thought that being a good forecaster doesn’t only mean being good at forecasts. Forecasts are no good unless someone is listening and is prepared to act.

Thinking about who is and who is not invested in certain outcomes – especially the status quo – can improve the odds when it comes to being heard. What you say is important, but so too is whom you speak to and how you illustrate your argument, especially in organisations that are more aligned to the world as it is than the world as it could become.

Steve Sasson, the Kodak engineer who invented the world’s first digital camera in 1975 showed his invention to Kodak’s management and their reaction allegedly was: ‘That’s cute, but don’t tell anyone.” Eventually Kodak commissioned research, the conclusion of which was that digital photography could be disruptive.

However, it also said that Kodak would have a decade to prepare for any transition. This was all Kodak needed to hear to ignore it. It wasn’t digital photography per se that killed Kodak, but the emergence of photo-sharing and of group think that equated photography with printing, but the result was much the same.

Good forecasters are good at getting other peoples’ attention using narratives or visual representations. Just look at the power of science fiction, especially movies, versus that of white papers or power point presentations.

If the engineers at Kodak had persisted or had brought to life changing customer attitudes and behaviours using vivid storytelling – or perhaps photographs or film – things might have developed rather differently.

Find out what you don’t know.

Beyond thinking about your own thinking and thinking through whom you speak to and how you illustrate your argument, what else can you do to avoid being caught on the wrong side of history? According to Michael Laynor at Deloitte Research, strategy should begin with an assessment of what you don’t know, not with what you do. This is reminiscent of Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous ‘unknown unknowns’ speech.

“Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know….”

The language that’s used here is tortured, but it does fit with the viewpoint of several leading futurists including Paul Saffo at the Institute for the Future. Saffo has argued that one of the key goals of forecasting is to map uncertainties.

What forecasting is about is uncovering hidden patterns and unexamined assumptions, which may signal significant revenue opportunities or threats in the future.

Hence the primary aim of forecasting is not to precisely predict, but to fully identify a range of possible outcomes, which includes elements and ideas that people haven’t previously known about, taken seriously or fully considered.

The most useful starter question in this context is: ‘What’s next?’ but forecasters must not stop there. They must also ask: ‘So what?’ and consider the full range of ‘What if?’

Consider the improbable

A key point here is to distinguish between what’s probable, and what’s possible. (See Introducing the 4Ps post).

Sherlock Holmes said that: “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.” This statement is applicable to forecasting because it is important to understand that improbability does not imply impossibility. Most scenarios about the future consider an expected or probable future and then move on to include other possible futures. But unless improbable futures are also considered significant opportunities or vulnerabilities will remain unseen.

This is all potentially moving us into the territory of risks rather than foresight, but both are connected. Foresight can be used to identify commercial opportunities, but it is equally applicable to due diligence or the hedging of risk. Unfortunately, this thought is lost on many corporations and governments who shy away from such long-term thinking or assume that new developments will follow a simple straight line. What invariably happens though is that change tends to follow an S Curve and developments tend to change direction when counterforces inevitably emerge.

Knowing precisely when a trend will bend is almost impossible but keeping in mind that many will is itself useful knowledge.

The Hype Cycle developed by Gartner Research is also helpful in this respect because it helps us to separate recent developments or fads (the noise) from deeper or longer-term forces (the signal). The Gartner model links to another important point too, which is that because we often fail to see broad context, we tend to simplify.

This means that we ignore market inertia and consequently overestimate or hype the importance of events in the shorter term, whilst simultaneously underestimating their importance over much longer timespans.

An example of this tendency is the home computer. In the 1980s, most industry observers were forecasting a Personal Computer in every home. They were right, but this took much longer than expected and, more importantly, we are not using our home computers for word processing or to view CDs as predicted. Instead, we are carrying mobile computers everywhere, which is driving universal connectivity, the Internet of Things, smart sensors, big data, predictive analytics, which are in turn changing our homes, our cities, our minds and much else besides.

Drilling down into the bedrock to reveal the real why.

What else can you do to see the future early? One trick is to ask what’s behind recent developments. What are the deep technological, regulatory of behavioural drivers of change? But don’t stop there.

Dig down beyond the shifting sands of popular trends to uncover the hidden bedrock upon which new developments are being built. Then balance this out against the degree of associated uncertainty.

Other tips might include travelling to parts of the world that are in some way ahead technologically or socially. If you wish to study the trajectory of ageing, for instance, Japan is a good place to start. This is because Japan is the fastest ageing country on earth and consequently has been curious about robotics longer than most. Japan is already running out of humans and is looking to use robots to replace people in various roles ranging from kindergartens to aged care.

You can just read about such things, of course. New Scientist, Scientific American, MIT Technology Review, The Economist Technology Quarterly are all ways to reduce your travel budget, but seeing things with your own eyes tends to be more effective. Speaking with early adopters (often, but not exclusively younger people) is useful too as is spending time with heavy or highly enthusiastic users of products and services.

Academia is a useful laboratory for futures thinking too, as are the writings of some science fiction authors. And, of course, these two worlds can collide. It is perhaps no coincidence that the sci-fi author HG Wells studied science or that many of the most successful sci-fi writers, such as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, have scientific backgrounds.

So, find out what’s going on within certain academic institutions, especially those focussed on science and technology, and familiarise yourself with the themes the best science-fiction writers are speculating about.

Will doing any or all these things allow you to see the future in any truly useful sense? The answer to this depends upon what it is that you are trying to achieve. If you aim is to get the future 100% correct, then you’ll be 100% disappointed. However, if you aim is to highlight possible directions and discuss potential drivers of change there’s a very good chance that you won’t be 100% wrong. Thinking about the distant future is inherently problematic, but if you spend enough time doing so it will almost certainly beat not thinking about the future at all.

Creating the time to peer at the distant horizon can result in something far more valuable than prediction too. Our inclination to relate discussions about the future to the present means that the more time we spend thinking about future the more we will think about whether what we are doing right now is correct. Perhaps this is the true value of forecasting: It allows us to see the present with greater clarity and precision.

Richard Watson April 2023. richard@nowandnext.com