If you think you’re busy, consider your frantic forebears.

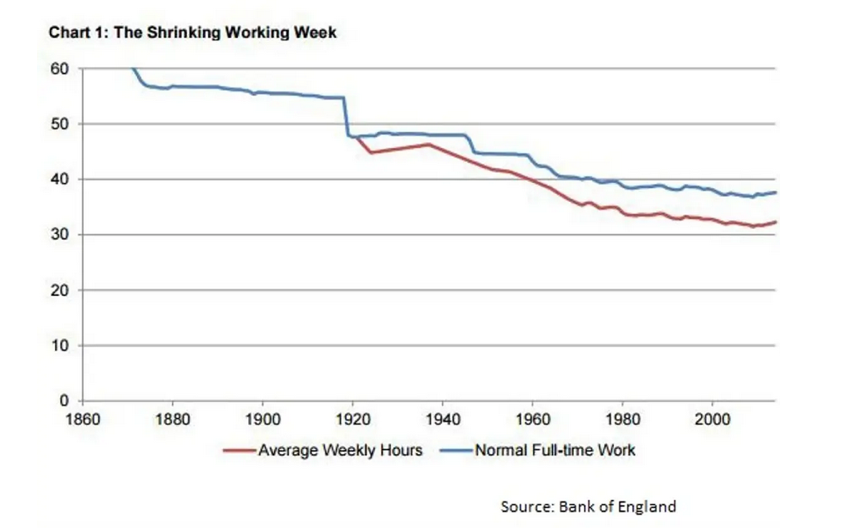

In the 1830s, 70-hour working weeks were considered normal in the UK.

There were no days off, except Sundays, and people had none of the time saving technologies that we take for granted nowadays either.

Thankfully, during the 1900s, the shift towards factory production and then office work, along with unionised labour and progressive legislation, caused these hours to almost halve. The figure fell to 40-hours a week after 1945, and now undulates moderately around this number.

These are averages remember. Work has never been equally distributed.

These numbers hide a multitude of harried households and lethargic loafers. Even so, the length of the typical working week doesn’t appear to explain why so many people feel so busy most of the time or why, according to one Gallup poll, people “don’t have time to do everything that needs to be done.”

Clearly, something odd is going on. Either the numbers are not giving us the true picture or else we’re wasting our time, rushing hither and tither in a mindless dance of exhaustion, something that the philosopher Seneca complained about 2,000 years ago.

In his essay In Praise of Idleness, another philosopher, Bertrand Russell, makes a plea for “happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves and weariness.” But he believed that such happiness would only occur if we did less work and developed what he referred to as: “a capacity for light-heartedness and play.” He believed this had been to some extent inhibited by the cult of efficiency.

He said this in 1935.

Little has changed since then, perhaps since Seneca’s time, except that the cult of efficiency has become a religion and we’re wearier, more anxious and less joyful than ever, especially at work.

I would like to consider two things in this context.

Firstly, I’d like to fleetingly consider what people spend their days doing, delve into why they might be feeling so busy, and examine why, deep down, some people might prefer being busy over and above a more leisurely lifestyle.

Secondly, I’d like to examine some of the consequences of being busy and consider a few alternatives. In particular, I would like to think about what we might not be doing, or achieving, by being so busy? Could we perhaps achieve more in the long run if we did less or acted slower in certain circumstances?

Let’s start with something that’s widely overlooked, which is societal acceleration. Almost everything is speeding up, along with our intolerance of things that are not. It’s called convenience and it runs a large part of the global economy and almost the entire digital economy.

Even walking speeds have accelerated. Gentle wandering has been overtaken by busy walking urgently focussed on a fixed destination.

In the early 1990s an American psychologist named n academic (Robert Levine) measured how long it took individuals in 31 different cities to walk 60 feet along an unobstructed pavement. 15 years later, a British psychologist (Richard Wiseman) repeated the research and found that walking speeds had accelerated by 10 per cent, with meandering Eastern cities catching up with their frenetic Western rivals.

Levine correlated this pace with economic well-being, population size, climate and, most interestingly of all perhaps, the degree of individualism vs. collectivism in a culture. Personally, I’d add incomes to this list because the richer people become the more valuable time becomes to them.

But before we rush along, one thing worth briefly examining is what exactly we mean when we use the term busy. In my view, when we think of someone being busy, we usually think in terms of someone having a lot to do, especially things that involve physical movement, someone rushing from one place to another or trying to complete a set task against the clock.

But definitions that hinge on rapid movement might be slightly out of date, especially when we consider the new world of work. Definitions involving movement largely date from a time when work was a largely physical process involving human muscle. We harvested things in fields and made things in factories. The faster people moved, the more work got done.

Being busy in this sense made sense. But these days, work is increasing something we do with our heads. It involves thinking, so being busy does not always equate with rapid movement let alone productivity.

Ann Burnett, a professor at North Dakota State University in the US, has studied the holiday letters of Americans going back to the 1960s, which she says serves as a proxy for the rise of busyness in America. Words that started to appear in the 70s and 80s — “hectic,” “crazy,” “consumed,” – are now increasingly common language, not only in the US, but elsewhere too.

As I said at the start, in the 1830s working six-days straight was considered perfectly normal, as were 70-hour work weeks, even for children. There were no annual holidays either. But throughout the 20th Century these hours declined significanly, so how can we account for this busyness?

The data varies slightly from survey to survey and from country to country, but overall the numbers show a clear, consistent and undeniable decline in the number of hours worked in almost every advanced economy in the world. Moreover, we no longer need to spend hours cooking our meals from scratch, washing our clothes by hand or cleaning our houses with brushes.

It’s possible, of course, that the numbers are wrong. People are notoriously bad at filling in time use surveys, but inaccuracies across every single survey?

I think not.

One explanation that I do subscribe to is that these numbers are averages and are therefore not reflective of the experience of millions of individuals.

Both work and leisure are fragmented, with some people receiving more and others receiving less. But even this explanation doesn’t ring true to me.

So, what on Earth is going on? Where is all the time going?

No matter how you slice the data, the vast majority of peoples’ time is spent doing just three things: sleeping, recreation and work. Surely, people can’t be busy sleeping, so that leaves work and recreation as the only possible culprits for contemporary busyness.

Let’s take a quick look at these starting with work.

Why might people feel so busy at work?

A 2019 study, quoted in The Times, says that the average worker in the UK spends 26 days a year in meetings, which is up from 23 days in 2018. Almost one million people claim to spend over half of every week in meetings and around a third say that this time is entirely wasted.

Pointless meetings could be one explanation for busyness at work. Another might be technology, more specifically, technology that does the exact opposite to what was intended. Email is a prime contender.

A survey quoted by the Huffington Post says that US workers spend 6.3 hours a day checking email, with 3.2 hours devoted to work emails and 3.1 hours devoted to non-work emails. This seems excessive, but as the cost of communications has rapidly fallen, the number of interactions has rapidly risen. Ease of use has led to rampant overuse. Daily work for many people now consists of nothing more than getting through their email inbox.

The wonderfully named Wasting Time at Work Survey, found that 89% of people admit they waste time at work with a small percentage claiming they waste more than half of a typical 8-hour workday doing things that have absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with work. What are these things?

Gorging on Google and flirting on Facebook top the list, but digital distractions are almost endless.

I could go on, but busyness beckons, so let’s look at recreation as the other potential culprit for why so many people feel so overwhelmed.

Again, I’m afraid the main culprit here might be technology.

Let me give you an example. I went through a spell of writing TripAdvisor reviews online. It all started innocently enough, but once you start it can be hard to stop. These companies really do know how to press our buttons, so we’ll click on theirs.

It’s called the ludic loop, a term that describes the way in which people are given tiny rewards in order to keep them coming back over and over again in a vain attempt to win larger rewards. Slot machines in Casinos are programmed to work the same way. Either way, I was being played.

TripAdvisor would send me emails saying that someone had found my review really helpful. This didn’t influence my behaviour at all, but emails saying I was in the top 1% of reviewers did. It got so bad at one point that I was going to restaurants, not because I was hungry, but because I wanted to write a review.

But it’s not just email, or social media, that’s causing a problem. As Douglas Adams once said: “Technology is anything that doesn’t work properly yet.”

I’ll give you another example.

Back in the day you put coins into individual parking meters and that was it. Then came a single machine that looked after numerous parking spaces and issued paper tickets. Recently this was upgraded so that payments could be made in advance and remotely using a phone. The latest development uses voice recognition. The idea is you say your car registration out loud and the machine recognises the number. Great when it works. Only sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes these machines don’t even recognise their own mediocrity. What should have taken 30 seconds for a friend of mine took well over 30 minutes.

Something else that’s happening is that companies are using us to do the work that was previously done by someone else. It happens at work, because companies no longer employ as many people as they should, and it happens outside of work too.

Self-check-out terminals in supermarkets are a good example. It’s hard to believe, but there was a time, not so long ago, when supermarkets employed people to do this for you and even packed your shopping into bags too.

All these things consume our time.

But I’m not sure that technology, or downsizing alone, quite explains it. I actually think most people are busy because they want to be.

By making ourselves busy, or at least by feeling busy, we shield ourselves from getting to know ourselves and other people better. A full diary is a way of hiding from people, especially ourselves. Busyness insulates us against thinking about what we’re really doing or where we’re really going.

As a New York Times article called The Busy Trap put it: “Busyness serves as a kind of existential reassurance, a hedge against emptiness; obviously, your life cannot possibly be silly, trivial or meaningless if you are so busy.”

Another reason people might like to be busy is the belief that if you give the outward impression that you’re a busy person then other people are less likely to trouble you. I once had a t-shirt with the slogan “Jesus is Coming. Look Busy”, which sums up the situation perfectly.

Employers, seeing someone briskly walking about the office, or running purposely between meetings, will assume that they’re working. In contrast, someone looking out of a window, quietly thinking, will generally be considered a time waster. One looks like work, the other looks like loafing.

There is possibly a third reason, too, which is that by saying you are busy you are saying that time is important to you, which is to say that you are important. Saying you are busy implies you are successful or attempting to be. Busyness is currency. It’s a form of status, a certificate of indispensability.

“How are you doing?” “Double busy”. “You?” “Yeah, same.”

But what might some of the other consequences of busyness be?

The bottom line is that taking one’s time can pay dividends. You’ve all heard of Charles Darwin and his book On the Origin of the Species, but did you know that while he wrote a draft of the book in 1839, he didn’t finish it until 1858.

Darwin’s book on earthworms took even longer, an astonishing 44 years.

How so? Well it was because Darwin liked to take his time. He was a self-confessed missionary for procrastination. Procrastination is a word that’s nowadays more associated with inefficiency than rigorous thought, but great insights and ideas don’t evolve overnight.

In a study looking at significant scientific discoveries in the 20th Century, Alan Lightman, a Professor at MIT, found that not being busy – or being “separate from the rush” as he put it – played a significant role, so Darwin isn’t an anomaly.

Contrast this approach with the deadline driven, outcome orientated, multi-tasking, need it tomorrow world of today, where people seem incapable of concentrating on any one thing for any decent amount of time. Putting to one side the health consequences of frantic busyness, what’s being lost here is the ability to dream, to explore and to think, especially curiously and creatively.

Reflective thought – which takes time – is linked to things like innovation, but also to something far more important too, which is the quality of human relationships.

In 1973, a classic study looked at whether the amount of busyness induced in a subject had a major negative impact on what the authors termed “helping behaviour” in an emergency. Turns out it did. In spades. The study was based on the parable of the Good Samaritan and the researchers had three hypotheses, one of which was that people that were rushed, busy or in a hurry would be less likely to offer assistance to someone.

I won’t go into the methodology in detail, but essentially participants were asked some questions and then asked to travel to another building to continue the experiment.

What the participants did not know was that the researchers varied the amount of time the subjects had to travel from one building to the next and gave different explanations as to what the subjects would be doing once they got there. On the way to the second building all of the subjects encountered a man who was slumped in a doorway, moaning and coughing. Clearly someone that might need assistance.

The researchers created a scale to indicate whether or not the subjects noticed the man and the degree of assistance that was offered: a Zero meant they stepped over the man on their way to the second building, whereas a Five meant they refused to leave him until help arrived, or insisted that they took him somewhere to get assistance.

You’ll have guessed the results already. The amount of busyness induced in the subjects had a significant impact on empathetic behaviour, even among subjects that were told they’d hear about the parable of the Good Samaritan in the second location. In low hurry situations slightly over 60% of people noticed the man and offered assistance, whereas in high hurry situations only 10% did.

I should point out that there was noticeable anxiety among many of the subjects once they arrived at the second building, including among those who failed to stop, which I suppose offers some level of hope.

I’d love to go on, but you are probably busy people. Suffice to say that I think you should all slow down and think outside of your in-box once in a while. Allow your mind to not only rest, but to wander also.

Einstein was famous for his daily walks in the woods. and Bill Gates took the idea further by having think weeks in a disconnected cabin in the woods. Carl Jung did much of his most creative thinking in his country house well away from his busy practice in Zurich. Even Jack Welch, formerly the CEO of one of the world’s most admired companies, General Electric, spent an hour each day looking out of the window

Neurologically, downtime like this is known as undirected thought and it’s extremely valuable in the context of original thinking.

The point here, and it’s an important one, is that in many instances, being away from work, or doing something that doesn’t appear to be work, makes people more productive, not less.

So, my suggestion that we all follow suit. Starting next week, add nothing to your diary. Schedule one hour each week to do absolutely nothing, certainly nothing that remotely looks like work. No email, no typing, no phone calls and especially no meetings. Look out of a window. Go for a walk. Or embrace Slow Media and read a physical book. If any of this works up the stakes. Embrace Slow Business. Do absolutely nothing for an hour each day, and while you are at it, slow down the general pace at which you do everything from walking and talking to emailing and eating.

If you think this this is impossible, possibly because you’re busy and important, here’s a video of Bill Gates talking to Warren Buffet about his diary.