I’d like to let you in on a little secret about the future, which is that there isn’t one.

Instead there are multiple futures, all of which can be influenced by how you, me and we choose to act right now. Moreover, how we imagine the future to be influences present attitudes and behaviours, much in the same way that our individual and collective histories help to define who we are. Put in a slightly different way, both past and future are always present.

But many people can’t see this. For them the future is something that just happens. It cannot be influenced. Increasingly, the future is also something that people fear, not something they look forward to. This is especially true in parts of the US and Europe.

This wasn’t always the case. The 1950s and 1960s were generally periods of great optimism, especially around technology. Even during the 1970s, 1980s and into the 1990s, the future was generally thought to be a good thing. It would bring more of whatever it was that people wanted.

But this view changed very suddenly. We were expecting trouble on 1 January 2000, but it was not forthcoming. Our computers still worked, our trains still ran and no planes fell out of the sky.

But then, on 11 September 2001, some lunatics armed with nothing more than a strong idea and a few feeble box-cutters flew two planes into the Twin Towers. On this date a number of Western certainties collapsed.

Or maybe the date was 9 November 1989. This was the day when the Berlin Wall fell down. This was meant to be a good day, an opening up of freedom and democracy. But it soon became apparent that two empires waged in a war of words on either side of the wall had meant certainty for almost half a century.

Whatever the precise date, it seems that many people no longer believe in the future. Indeed, many people seem to have fallen out of love with the very idea of progress – the idea that tomorrow will generally be better than yesterday.

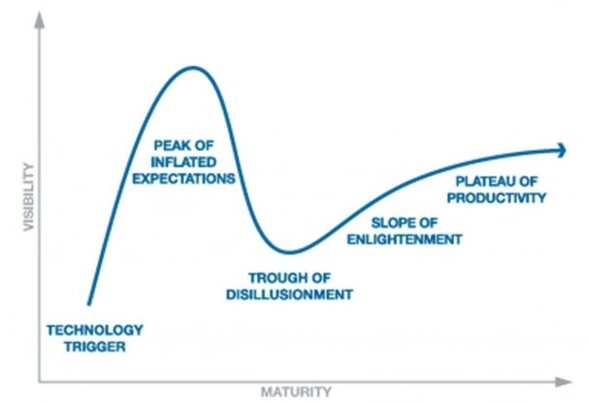

Back in the early 1970s, Alvin and Heidi Toffler wrote a best-selling book called Future Shock. In it the authors argued that too much technological change, or at least the perception of too much change, over what was felt to be too short a period of time, was resulting in psychological damage to our Stone Age brains. The Tofflers also placed the term ‘information overload’ into the general consciousness.

In many ways, the idea of future shock is similar to that of culture shock. Both refer to the way in which individuals feel disorientated and to some extent powerless as they move from one familiar way of life to another. In the case of culture shock, this usually refers to the physical movement from one country or culture to another. In the case of future shock, we might use the term to describe our shift from analogue to digital culture or from a period containing what were thought to be fixed truths and geopolitical certainties to an era where boundaries are more fluid and nothing seems to be very certain.

The rapid change argument is certainty plausible. Adherents to this argument could cite Moore’s Law in the case of computing or rapid developments in synthetic biology, robotics, artificial intelligence or nanotechnology – or perhaps the breathless expansion of social media – as evidence for their case.

But was it not ever thus? The Internet, a fundamentally disruptive technology, can be compared in terms of impact with the rapid development of the telegraph, railways or even electricity in Victorian times. In fact I met an old gentleman not so long ago who was defending the erection of a mobile phone mast. Apparently, there was a similar fuss when the streetlights were first put in.

As for recent developments in the Middle East, history does seem to repeat itself, often as tragedy and sometimes as farce, as Karl Marx once observed.

Many things are indeed changing, but this has always been the case. Moreover, many of our most basic needs and desires – for example our quest for human connection, our sense of fairness, our need to belong to a community and our love of stories have hardly changed.

We still eat. We still drink. We still fall in and out of love. We still watch movies. We still listen to music. We still wear clothes and wear wristwatches. Actually I’m not totally sure about that last one. A friend of mine told me that he’d recently given his twelve-year-old son a watch for his birthday. The kid looked rather perplexed and asked why his father had given him a “Single function device.”

But I don’t think that the Swiss watch industry has much to worry about. Indeed we have been here before in the late 1970s when watches first went digital. People in the industry initially panicked, but then calmed down once they realised that people don’t buy watches just to tell the time.

Indeed, focusing purely on logic sometimes misses the point in the same way that focusing on technology at the expense of psychology can get you into a whole heap of trouble.

There are also cycles. I’m old enough to remember not only bicycles, but also beer and cider and a host of other things ranging from butter to bespoke suits being written off one moment and being reinvented and reinvigorated the next. As someone once said, there’s no such thing as mature industries, only mature executives that think certain things are impossible.

So why is pessimism about the future all the rage? To a great extent this is a Western phenomenon. If you speak with people in Mumbai, Shanghai or Dubai about the future there is generally more optimism on the streets. But even here there are worries surfacing that relate to everything from rapid urbanisation and income polarisation to water security, food prices and pollution. Fear of change, it seems, is increasingly universal. Why could this be so?

You might cite globalisation. Globalisation has brought many benefits, but as the world flattens and becomes more alike, cultural identity is coming more important. Indeed, the more globalised the world becomes, the more the local seems to matter and the more that historical differences come to the surface.

A loss of cultural identity could be a reason for the unease. But there are many other contenders. The economy is another potential culprit. One could also mention the number of people living on their own, the fear of unemployment, the blurring of work and home life, the breakdown of marriage, the decline of trust or the general acceleration of everyday life.

It could also be due to the (supposed) Wane of the West – the idea that the American and European Empires are falling while those of China, Russia, India, Brazil, Africa and others are all on the rise. These are all credible explanations, but I don’t think that any, or all, are quite right.

I would like to suggest an answer in three parts.

First, I think we are anxious because we are indeed exposed to too much information. The Toffler’s were right, they were just 40 years wrong.

What you don’t know can’t hurt you as they say, but in a digitally connected world everything, it seems, is visible and therefore everything has the potential to hurt or to embarrass you. Reputational risk is everywhere, not only for institutions but for individuals too.

I am not only referring here to privacy and the immortal nature of digital stupidity. I am also pointing towards cyber bullying, data and identity theft and a world in which we are all being watched, not by Big Brother, as Orwell predicted, but by our own social networks. These networks claim to be connecting us, but in so doing they never leave us alone and never allow us to be our real selves.

Second, I think we are anxious and worry about the future when we haven’t got anything more serious to be concerned about. Hence we imagine risks that barely exist or blow the risks that do exist out of all proportion. We indulge in self-loathing for similar reasons. As a species we have achieved a lot over the last few thousand years. If you look at almost any measure that matters – numbers ranging from infant mortality and adult longevity to literacy rates, extreme poverty, access to education, health, the number of women in education, the number of women in the workforce or the number of people killed in major conflicts we have rarely had it as good as we have it today.

But we don’t see this. What we see instead is the idea that progress itself has somehow become impoverished.

The popular view is that although technology and GDP have advanced, morals and ethics are treading water or, depending on your choice of broadcaster, are sinking back into decadence or barbarism. I would suggest that the reason for this has something to do with our own megalomania, our own sense of importance. I think it also has something to do with a lack of purpose and narrative, which brings me onto my third and final point.

I believe that the reason so many people around the world are anxious is because they can no longer see what lies ahead.

Back in the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s, people believed that the future would be a logical extension of the present. They were wrong, deluded in many instances, but this hardly matters. What does matter is they had something – and it really could have been anything – to aim for and to orientate around.

But now we no longer believe in such things. Outside of a few pockets of massive wealth and/or techno-optimism, we have somehow fallen victim to the idea that the future is something that just happens to us. Something to which we can only react. Something we can do nothing about.

But this attitude is nonsense. The only thing we know for certain about the future is that it’s uncertain. And if it’s uncertain there must be a number of potential outcomes, a number of different ways in which the future might unfold. And all of these futures can, to a greater or lesser extent, be influenced by what we, as individuals and society, decide we want.

This, if you’ve not figured it out already, is intimately connected with leadership and to some extent innovation. In both cases an individual, or sometimes a small group, has a vision of a world that they’d like to see. This individual, or group, then creates a compelling story, a vision if you like, and convinces others around them to join them on a journey.

And that, I suppose, is the challenge.

Yes, we should all be aware of the drivers of change at both a global and local level.

We might, if we are not doing so already, consider the potential impacts of ageing societies, water and other resource shortages, climate change, the changing nature of influence, the impacts of re-localisation, the growth of more sedentary lifestyles, the shift from paper to pixels and its impact on understanding and the digitalisation of both friendship and community.

We should also imagine what various futures might look like and consider how we’d react if certain futures unfolded. We should develop a scenario for a world that turns out much better than we currently expect. We should also create a scenario for a world that gets much worse than we expect. We may even want to build a scenario for a future that turns out far weirder than we expect.

But fundamentally we need to make a choice. We need to decide, as individuals, organisations, nations or indeed the whole planet, where it is that we want to go next and start moving in that direction.

Last year Facebook launched a virtual assistant. It was called Moneypenny after the secretary in the James Bond books. Yet again, a vision of the future was shaped by the past, possibly with a nod to Walt Disney’s Tomorrow Land in the 1950s. Is this sexist or just a natural outcome of the fact that more than two thirds of Facebook’s employees are men? Whatever the reason, the future is generally shaped by white, middle-aged, male Americans. The majority of the World Future Society’s members are white men aged 55 to 65 years of age and when it comes to the media’s go-to guys for discussing the future they’re men too. What this means is that visions of the future are overwhelmingly created by – and to some extent shaped for – a tiny slice of society, one that’s usually in some way employed in science or technology and has not had to struggle too much.

Last year Facebook launched a virtual assistant. It was called Moneypenny after the secretary in the James Bond books. Yet again, a vision of the future was shaped by the past, possibly with a nod to Walt Disney’s Tomorrow Land in the 1950s. Is this sexist or just a natural outcome of the fact that more than two thirds of Facebook’s employees are men? Whatever the reason, the future is generally shaped by white, middle-aged, male Americans. The majority of the World Future Society’s members are white men aged 55 to 65 years of age and when it comes to the media’s go-to guys for discussing the future they’re men too. What this means is that visions of the future are overwhelmingly created by – and to some extent shaped for – a tiny slice of society, one that’s usually in some way employed in science or technology and has not had to struggle too much.