Here’s the text of my recent TEDx talk in Germany. Note that these are only my notes and not what actually came out of my mouth…

If you gave an infinite number of futurists an infinite amount of time, would one of them eventually be correct about something?

I wrote a book a few years ago about what I thought might happen over the next 50 years. Ever since I’ve been called a futurist and I’m now regularly called upon to make predictions.

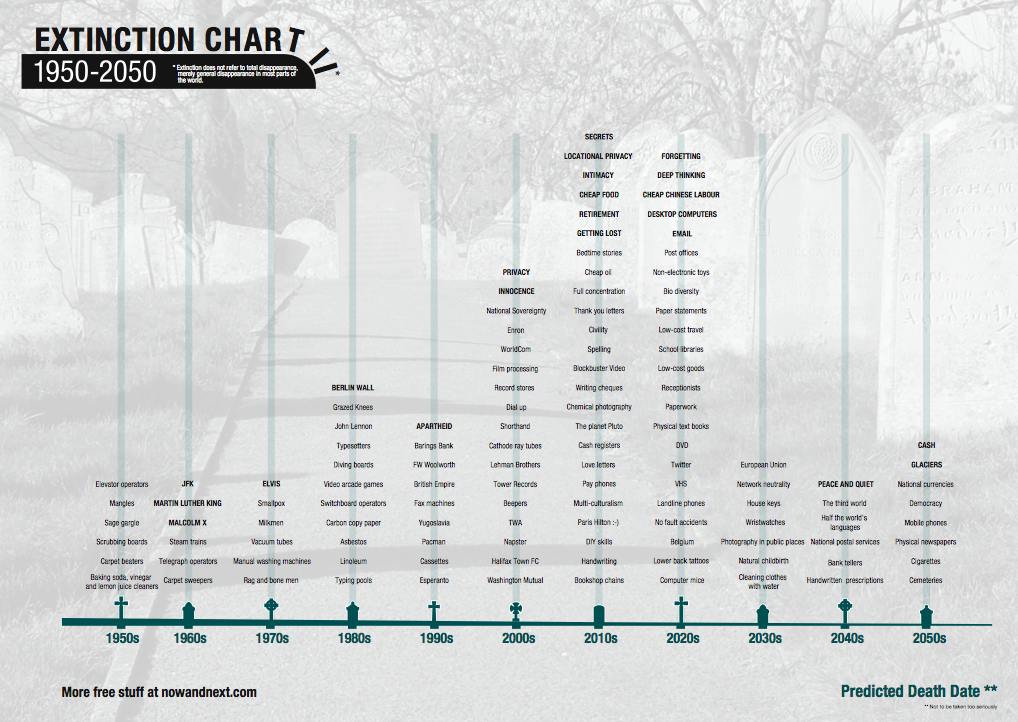

But the history of prediction isn’t particularly good.

For example, in 1886, the engineer Karl Benz predicted that: “The worldwide demand for automobiles will not surpass one million.” Eight later, in 1894, an article appeared in the Times newspaper in London predicting that: “In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under 9 feet of horse manure.”

How could they have got things so wrong? Simple. Both predictions were based on past experience. They were extrapolations built upon what turned out to be short-term trends. Both used critically false assumptions.

In the case of Karl Benz the mistake was to assume that cars would always require a chauffeur and that the supply of skilled chauffers would eventually dry up. In the case of London being buried under horse manure the mistake was to assume that the volume of horse transport would increase indefinitely alongside population. The article also totally misjudged the disruptive impact of motorised transport, invented by the aforementioned Mr Benz.

On the other hand, the accuracy of some predictions can be rather good, especially if you give them enough time to come true. Hindsight, it would appear, is a necessary accompaniment to futurism.

A few years ago I picked up a couple of old books in a junk shop in the middle of the English countryside. The first was called Originality and was written by T. Sharper Knowlson in 1917. Here he is quoting Sir Aston Webb about the Future of London from the perspective of 20th January 1914 .

“There are two great railways stations, one for the north and one for the south. The great roads out of London are 120 feet wide, with two divisions, one for slow-moving and the other for fast-moving traffic; and there will be a huge belt of green fields surrounding London.”

Not bad. Or how this passage from the second book I bought, which was Future Shock written by Alvin Toffler in 1970:

“The high rate of turn-over is most dramatically symbolised by the rapid rise of what executives call ‘project’ or ‘task-force’ management. Here teams are assembled to solve specific short-term problems. Then, exactly like the mobile playgrounds, they are disassembled and their human components re-assigned. Sometimes these teams are thrown together to serve only a few days. Sometimes they are intended to last a few years. But unlike the functional departments or divisions of a traditional bureaucratic organization, which are presumed to be permanent, the project or

task-force team is temporary by design.”

Remember, this book was written more than 40 years ago. In sounds like Silicon Valley in 2011. The list goes on. Peter Drucker wrote about portfolio careers in 1988 and Warren Bennis was writing about the need for radical innovation in the late 1960s.

And let’s not forget HG Wells launching ballistic missiles from submarines in The Shape of Things to Come in 1933, Arthur C. Clarke envisioning a network of communications satellites in geostationary orbit above the earth in 1945 and Captain James T. Kirk using what appears to be a Motorola cell-phone way back before any such thing had been invented.

Admittedly some of these are broad concepts rather than specific predictions, but this doesn’t negate the fact that a few seers do occasionally get it right and that the future would be a good subject for serious study if only the sources were more forthcoming.

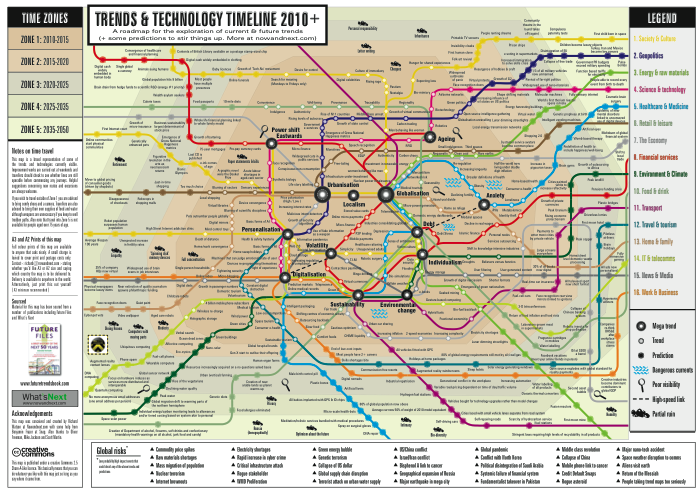

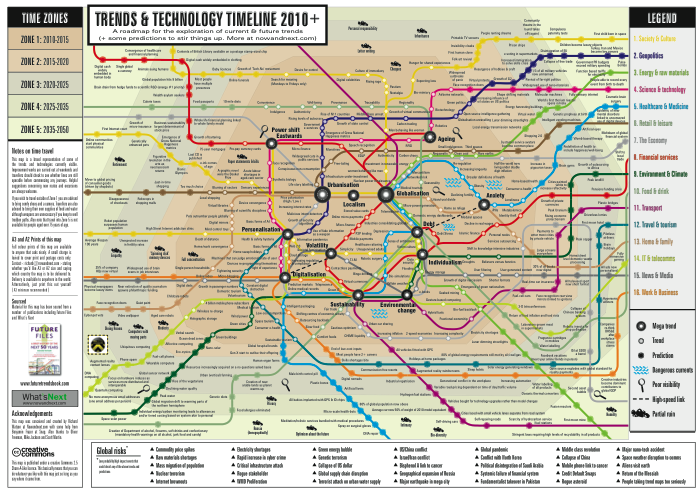

Of course, what you really need when you are thinking about distant horizons is a map, so I designed one last year. It contains far too much information and is far to complex, but then that’s probably the future isn’t it?

The outside of the map contains a series of predictions that get more playful and more provocative as you move out towards the edges. For example:

• There will be a convergence of healthcare & financial planning

• We will have face recognition doors & augmented reality contact lenses

• Online communities will start physical communities

The centre of the map contains some mega-trends such as globalisation, urbanisation, sustainability, volatility, the power-shift Eastwards, ageing, anxiety and so on. But be careful. Trends like these can get you into all kinds of trouble. In fact they can easily get you into more trouble than predictions because people believe them.

Firstly, trends represent the unfolding of current events or dispositions. They tell us next to nothing about future direction let alone the velocity of events. They do not take into account the impact of counter-trends, strange combination or anomalies.

But there’s an even bigger problem, which is that in my view there’s no such thing as the future. The future is ambiguous. It’s uncertain. Therefore, there must surely be more than one future. In other words, there must be a number of alternative futures.

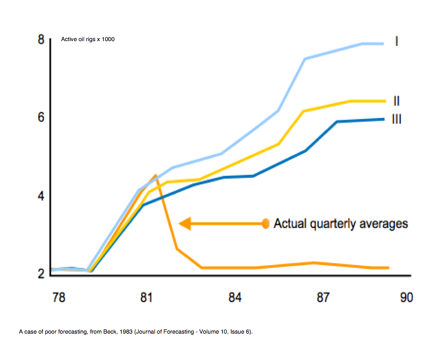

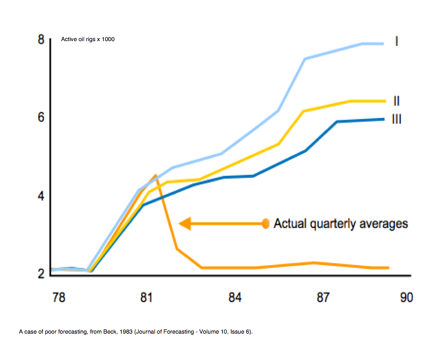

Look at this chart for instance. This shows a series of forecasts about the number of active oilrigs drawn up by an oilfield supplies company in the early 1980s. Someone looked at the data and produced a series of entirely logical high, medium and low predictions (I, II & III). The bottom line is reality.

What nobody foresaw was that what looked like a long-term trend was in fact a short-term situation based on a high oil price, low interest rates and government subsidies. In short, they failed to see that while all our knowledge is about the past, all of our most important decisions are about the future.

So what can we do to address this central problem of prediction? Is there any point whatsoever in trying to predict the future or is it best just to sit back and let it happen?

Letting the future happen is actually not a bad option, but only if you are nimble. If you have an open mind and can move quickly a fast follower strategy can work. But most organizations are neither nimble nor open. They are mentally closed to the outside world and stuck with assets and systems that were created in the past. Most organizations are built around historical ideas and are constrained by various legacy issues and are concerned with numbers that relate to the last 12 months and worry about what will happen to these numbers over the next 12 weeks.

A much better bet, in many instances, is Scenario Planning. This has its origins in war gaming or battle planning, especially a 6th Century Indian game called Caturanga, meaning four divisions, and Kriegsspiel, a German war game invented in 1812. War gaming is still used by the military today, but also by companies such as Shell, who use narrative scenarios to look at the potential impact of a number of external variables on strategy or long-term capital expenditure.

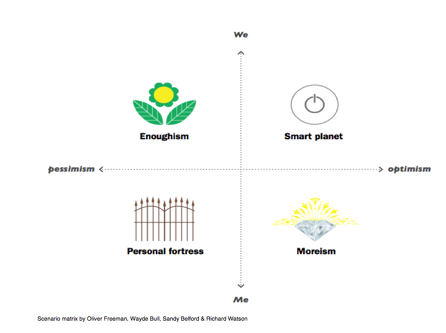

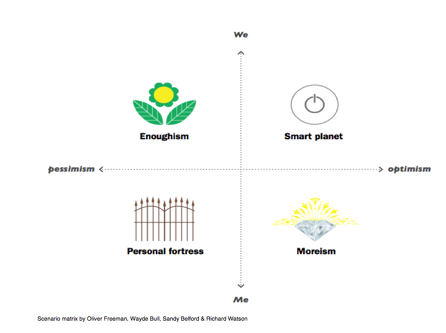

To illustrate how scenarios work here’s a set of scenarios I did with some friends a few years ago. When you do scenarios you generally start with a focussing question and I like to explain this by asking people to imagine that time travel really exists and to prove it the inventor has just come back from the future to say hello.

If you were allowed to ask this person just one question what would it be? Now I should explain that questions like “when will I die?” or when will the USA soccer team win the World Cup aren’t allowed. The question is supposed to relate to work, although if you were to do a personal set of scenarios then it would be fine.

In this case the question was simply around future customer mindsets. You’ll notice that there’s a vertical and a horizontal axis. These are created by finding two unrelated forces that are both highly impactful and highly uncertain. In this instance there’s one axis built around activism versus passivism (‘We’ versus ‘Me’ if you prefer) and one built around optimism versus pessimism, which is created by attitudes towards the economy and climate change.

Once you impose one axis against the other four divergent futures are revealed, each of which becomes more distinct and extreme as you move outwards from the middle.

Starting in the bottom right corner we have a scenario called Moreism. The key drivers creating this scenario are optimism and individualism, so we get a world of globalisation, free markets, materialism and economic growth at almost any cost.

This is a world primarily driven by greed.

Moving across to the bottom left, we get a scenario where the drivers are pessimism and individualism. So this is a world where people essentially give up hope and move into a survivalist mindset. It’s a world initially dominated by local community and self-reliance, but as you move outwards it starts to incorporate protectionism and to some extent isolationism – even xenophobia – where hatred is focussed upon anyone that is not considered to be part of the group. In a word, it’s a world driven by fear.

Moving up to the top left we have Enoughism. This is obviously the polar opposite to Moreism. It’s a world where people decide that they’ve got enough and that they’ve had enough. It’s a world where people decide to change how they live in relation to the planet and reinvent many of the institutions, models and structures that have grown up over the past hundred years. It is very sustainable, very ethical and very community driven. It is a post-materialist world where work-life balance features strongly, as do social value, meaning, purpose and happiness. It is to some extent idealistic and certainly altruistic.

Finally, in the top right, we have Smart Planet. This is a world driven by a strong belief in the power of science and technology. A world powered by human imagination and ingenuity. An accelerated world of genetics, robotics, internet and nanotechnology, where smart machines reshape the world. However, there are some unexpected counter-trends. Alongside emotionally aware machines and augmented reality we see a need develop for physical objects and human interactions. It is smart and efficient, but this creates a certain coldness, so people crave heart and soul.

But there’s still a problem here. The point of scenarios such as these is to help people to anticipate change. To foresee, to some extent, a range of alternative futures against which current thinking and strategies can be tested. But whilst it’s possible to track emergent scenarios – even to develop contingency plans for each eventuality – at the end of the day I think you have to commit.

Cast you mind back to the map and some of the trends in the middle. One of the trends was anxiety, which I said was caused by several of the other trends. But it’s also caused by the fact that people no longer have a clear view of what lies ahead.

Doing nothing and waiting for the future to unfold is one option. Making a series of educated guesses – deeply questioning why things are happening and asking what might happen next is a much better idea. But there’s a third option. Leaders are supposed to have a clear vision of what can be achieved and what the future could look like if we take a certain path. Unfortunately, most leaders nowadays don’t do this. They wait to see what the majority of people want and then they say that they agree. This is despite the fact that most people don’t know what they want and soon forget what they’ve said. Similarly, CEOs and politicians will not agree to anything that takes to long or is too difficult to deliver.

But we can all be leaders. We can all drive things forward ourselves. All we have to do – as individuals, countries, corporations, even the entire planet – is to decide upon where it is we want to go and to slowly start moving in that direction. In other words, we need to pick the future we want and start building it. This will be difficult. We will get many things wrong. But if we could at least agree amongst ourselves where we are going we would soon start to re-perceive the present and the future would be a much better place to live.